Romancing a Royal Favour: The Dedication Page of Emma

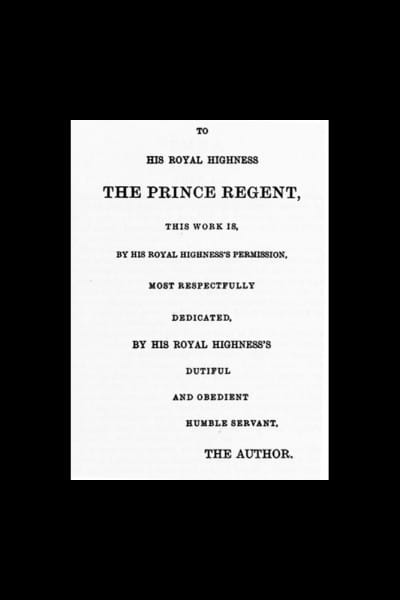

Of the six novels written by Jane Austen, Emma is the only one to include a dedication page. It reads, "To His Royal Highness, The Prince Regent, This work is, By His Royal Highness' Permission, Most Respectfully Dedicated, By His Royal Highness's Dutiful and Obedient Humble Servant, The Author." It is indeed remarkable for a novel, which does not even bear the author's name, to feature the insignia of the Prince Regent on its spine as well as a formal dedication to the future King of England. As a Tory sympathizer, Austen was not a fan of the regency, which relied heavily on a parliament controlled by the Whigs. On several occasions, Austen disclosed her disliking for the frivolous and flamboyant Prince Regent. The humble tone and regal manner of the dedication therefore is confusing—to say the least!

The "disreputable and somewhat ludicrous" Prince Regent was far from popular in his time. He came to power after his father, the mentally delusional King George III, was declared unfit by the Parliament. The Prince's reckless behavior in both private and public spheres made him an undeserving candidate for this new role. Soon after coming to the throne, he tried to get a formal divorce by scandalizing his wife. The Prince launched a "delicate investigation" to pry into his wife's alleged secret love life. The Prince earlier was forced by his advisory council to marry Caroline of Brunswick to settle his financial debts. As Prince Regent, he announced his wife "unfit" and unworthy of receiving visits from their daughters. In response, Princess Caroline wrote a passionate letter to her husband, which her Whig supporters later published in The Morning Chronicles.

Austen reacted to the news in a letter written to her friend Martha Lloyd in February 1813. She wrote:

I suppose all the World is sitting in judgment upon the Princess of Wales's Letter. Poor woman, I shall support her as long as I can, because she is a Woman, & because I hate her Husband — but I can hardly forgive her for calling herself 'attached & affectionate' to a Man whom she must detest ... I do not know what to do about it; but if I must give up the Princess, I am resolved at least always to think that she would have been respectable, if the Prince had behaved only tolerably by her at first. ("Letter 82")

Austen here champions sisterhood in framing her sympathy for Princess Caroline. She is at the same time reflecting on the idea of ultimate male responsibility for female behavior," an idea that is central to Austen's 1813 novel, Pride and Prejudice where Darcy is the idealized gentleman who identifies and controls feminine impropriety. Similarly the protagonist Emma in the novel is constantly disciplined by her future husband George Knightley. Emma manages to emancipate herself at least in her imagination and refuses to submit to any authoritarian figure. The same can be said of her creator, Jane Austen—a fact that only adds to the dedication dilemma.

Austen was in the middle of writing Emma in June 1814 (the novel was composed in fourteen months, from January 21, 1814 to March 29, 1815), when the Prince Regent offered a huge banquet for several heads of states to commemorate a victory in a battle over Napoleon. The celebration was followed by an extravagant parade to which Austen responded, "I long to know what this bow of the Prince will produce." It is strange that Austen decides to dedicate her book to someone whom she detests. The background of the dedication therefore merits detailing.

In October 1815, Austen came to London to take care of her brother Henry who was ill. At the same time, she was negotiating her fees with her 'civil-rogue' publisher John Murray ("Letter 121"). Henry's doctor Charles Haden was an acquaintance of Prince Regent's physician. The news that the author of Pride and Prejudice was in town reached the Prince who in turn asked his librarian Rev. James Stanier Clarke to arrange for Austen a guided tour of his Carlton House library.

During the tour Clarke told Austen that "The Regent has read and admired all [her] publications" and the Prince Regent even had a set of all her books in all of his residences. He added, "Lord St. Helens and many of the Nobility who have been staying here, paid you the just tribute of their Praise" ("Letter 138A"). At one point of the tour, Clarke suggested that Austen could consider dedicating one of her future books to the Prince Regent. Austen was a bit surprised by the proposition. She later wrote to Clarke, asking whether it was 'incumbent' upon her "to shew my sense of the Honour, by inscribing the Work now in the Press, to HRH" ("Letter 125 D"). Clarke replied, "It is certainly not incumbent on you to dedicate your work now in the Press to His Royal Highness; but if you wish to do the Regent that honor either now or at any future period, I am happy to send you that permission" ("Letter 125 A").

A confused Austen discussed the matter with her sister Cassandra, brother Henry and publisher Murray. The correspondence is evident in her letter written to Cassandra: "I did mention the PR in my note to Mr. Murray, it brought me a fine compliment in return; whether it has done any other good I do not know, but Henry thought it worth trying" ("Letter 128"). She probably thought of the PR (Prince Regent) insignia as nothing more than a PR campaign. Austen thus went ahead with the suggestion, and asked her publisher to make specially bound copies for the Prince Regent. Accordingly, Murray made presentation copies in scarlet with the Prince of Wales's feathers on the spine of the volumes and, as instructed, sent them to Clarke three days before the book was publicly available.

As it appears in the first edition, the dedication page seems like a last minute insertion. It is placed before the front leaf where normally the half-title page appears. Because of this late adjustment, the half-title page is found at the back leaf of the first volume. Austen requested Murray to include the dedication on Monday December 11, 1815, even though the book was advertised to be published in the coming Saturday ("Letter 130"). Her ignorance of, if not indifference to, royal protocol is apparent in her instructions: "the Title page must be, Emma, Dedicated by Permission to H.R.H. The Prince Regent". Fortunately for Austen, Murray saved her from a potential protocol blunder by rewriting the title page as mentioned above. Austen was quick to thank her publisher for 'putting her right', adding: "Any deviation from what is usually done in such cases is the last thing I should wish for" ("Letter 131").

The royal librarian graciously acknowledged receipt of the "handsome copies" of the novel on December 21, stating that the copies had "gone to the Prince" ("Letter 132 A"). He went on to request Austen to write another book on the House of Saxe Cobourg from the perspective of a clergyman with a dedication for his new master, the Prince's new son-in-law Prince Leopold. Austen made light of the situation, saying that she would keep to her own style as she had no plan of writing a historical romance, and stalled the possibility of any further royal dedication. Austen continued to maintain a lukewarm correspondence with Clarke. When Clarke informed Austen of his promotion in the household of Prince Leopold, she curtly replied: "The service of a court can hardly be too well paid, for immense must be the sacrifice of Time & Feeling required by it" ("Letter 138A" 311).

Austen's characteristic irony makes it difficult to ascertain whether this comment is actually meant as a compliment on Clarke's success or on her own failure to gain anything out of the courtly service rendered to the Prince. After all, the time and feeling employed by Austen in including the dedication earned her nothing but a "fine compliment."

The author is Professor of English, University of Dhaka. Currently on leave, he is the Head of the Department of English and Humanities at ULAB.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments