Experiencing Conrad’s Lands and Understanding His Tales

I have had the opportunity of living for some time in Conrad's fictional places, namely Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo) and Malaysia's eastern province Sarawak's adjoining country in Borneo Island, Brunei Darussalam. In Congo, I worked as a peace keeper and in Brunei, as a diplomat. Though Brunei hid in Conrad's novel Lord Jim as a surreptitious land, it was, in fact, the centre of British influence in Malay Archipelago. But it came as a surprise to me as I failed to discover in either of the two countries a single reader who read Heart of Darkness or Lord Jim. Joseph Conrad was an unfamiliar name to them even if they were well-read.

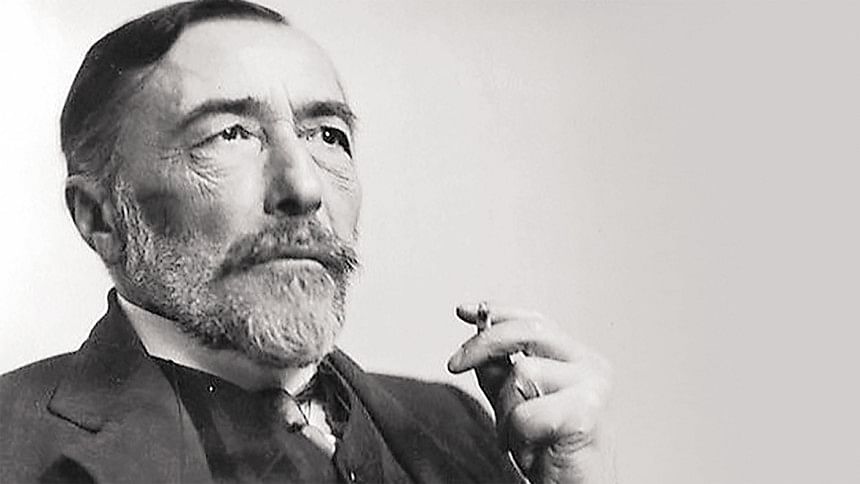

Conrad was of Polish origin and learned English not till he was in his early twenties. To me, more significant than his being a writer was the fact that he was a sailor by choice. He learned seamanship and writing with the dedication and labors of a fanatic. He created a style in English fiction, inimitable and fascinating, that blended with his ardent weakness for both. His non-English sensibility in prose makes him appealing to readers who are baffled by the turbulent forces of nature and tragic setting of human fatality.

Conrad travelled to Congo at the turn of the nineteenth century when Europe's mission to civilize Africa was at the height of its missionary fanaticism. His maritime peregrinations had an evangelical purpose. Many contend that he was racist, and his literary mood was influenced by the European expansion of colonial conquests of the time. I would not so much deny the possibility of racist streak in his character, had I not witnessed Congo and its society from close quarters. The society of Congo is very different from European society and is divided into tribes, and even in the 21st century, its social moorings are imprisoned in the archaic tradition of pre-historic institutions. During peace negotiations, I often found that it was simple for Africans to indulge in the spirit of internecine conflict. The choice of being rational was an anathema to an African, and he rejoiced in being irrational because it was married to his tribal ethos of historicity, chivalry and group dynamics. So, for a French, or a Belgian, or an English, the task of "civilizing" a black African might have seemed like a universal duty. Conrad must have failed in his duty; otherwise he would not have given his short novel such a despairing title. But like any other European with a "spirit of high moral grounds," the project of colonialism was bound with the act of realizing the universal principles of European civilization. Conrad, as a writer, may have felt it necessary to do this in a language which was not his by birth but he did so with extraordinary panache. Does this refinement in Conrad's oeuvres make him a racist? I would not agree.

Why did Conrad name Congo "Heart of Darkness"? For someone used to bright sunny morning of European sky, Congo represented an infernal depth of human habitat. Conrad's Congo was a dark land but its darkness had a beauty of supreme lucidity gifted by nature. I assume Conrad's journey through its rivers to remotest places had kept his chances to witness the lustre and sheen of deep forests and jungles that shrouded the mystery of its anthropomorphic character away from his sight. Where the light of the sun was never allowed to penetrate, the only solace left underneath the canopy of thick overarching foliage was one of apathy and fear. When I visited Congo two decades ago, it was more than a century after Conrad made his own journey into what he described as the mysterious uncharted womb of a barbaric land. Our base was located at Bunia, the capital of Ituri province. As a pilot, I had to fly to distant places and often my heart dried up in fear.

Congo is sixteen times the size of Bangladesh. The infinite expanse of impenetrable dark shadow of forests covering the ground reminded me of Hades. There was no patch of open field for an emergency landing. Nature appeared mysterious, esoteric and animalistic. Its equanimity was preserved in the immense vastness of forests, jungles and untamable lakes. In the morning, from the camp, one could see the rising steepness of mountains covered with gray trees reaching up to the ocean of a blue sky bewitched by its own somberness and sorrow. Congo as a country was sunk in grief as its moments were pregnant with internal conflicts and deaths. Conrad's agility lay in giving life to Congo's quiet and undisturbed nature through words, sentences, expressions, imageries and symbols, a permanent place of reading in history. I felt that Heart of Darkness claims a place in the study of human civilizations.

The story of Lord Jim is even more enticing from point of its truth-like historical antecedent. Lord is an English rendering of the Malay word Tuan meaning Lord. Jim is a character modelled after James Brookes, the first White Rajah of Sarawak province of Malay Archipelago. The story goes back to the later part of the first half of the 19th century when the British established their rule in the Malay Peninsula. It is with Brunei that Jim's links are connected. At one time, the Sultanate of Brunei constituted the vast territory of Borneo, a chunk of Sulawesi and bits of the Philippines. Internal factions, conflicts and wars reduced such a huge sovereign land to present-day Brunei Darussalam. History says it was all because of James Brookes, the first British resident in Sarawak with full sovereign powers of a ruler extracted from the authority of the Sultan of Brunei in favour of protecting the latter's crown. While Malays look upon James Brookes as an infidel who took their land away, Conrad invests him with the character of a righteous Englishman bound by both fate and duty to honour the principles of a civilized life.

In real life, Brookes developed a very close, cordial and affectionate relationship with the Crown Prince Muda Hashem who was entrusted into his care and physical protection by the Sultan himself. In one of the palace intrigues, Sultan's own relatives were involved with some foreign scoundrels in dispossessing him of the throne. It was Brookes and his army that saved him from being assassinated. But due to Brooks' miscalculation, the Crown prince was later murdered by the Sultan's enemies. Brooks was repentant, and agonized over his folly. It is in this juncture of history that Conrad breaks himself off from the truth and makes his story a virtual recapitulation of personal figment. I think it is in this exceptional divorce from real life events that makes Conrad's novel so captivating and morally disturbing yet uplifting. Real James Brookes, upon retirement, leaves Malay Peninsula and settles down in England with a lot of wealth extracted from his stay in Borneo. The imaginary James Brooks, nee Lord Jim, gives himself up to the Sultan and hands himself a pistol to the Sultan who shot him to avenge his son's death. Conrad has revolutionized Jim into a much more dignified, ethereal and honorable man of the western civilization. This imposition of superman upon the structure of an ordinary English gentleman was Conrad's ploy to show the readers the virtues of a civilized life. An Englishman ought not to be afraid of death if it falls in the path of conviction.

Lord Jim might upset a reader if read against the background of Borneo's scenic beauty. While Congo presents the gorgeousness of a dark nature, Borneo offers the splendours of a crystalline and pristine nature. Much of its landscape soothes the nerves with profound repose in tranquility. Brunei gave me a different kind of feeling than Congo. But it would be amiss if we failed to recognize that during Brooks' time, much of Borneo was fractured by internal strife and deadly murders. Head-hunting was one of the common practices among the indigenous people. Again Conrad made Lord Jim the peacemaker by instilling the norms of civilization among the Asians.

I have enjoyed my stay in Congo and Brunei as much as I enjoyed my reading of Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness. Christopher Marlow, the narrator was present at both places; and like him, I have tried to understand the mind of Joseph Conrad in an impersonal way. Creating characters like Jim and Kurtz are difficult propositions because it is through the portrayal of their characters that the superiority of a race or nation is anticipated. Reading Conrad, one must not forget that the virtues of an individual may seem at times hard to comprehend because they pit against the social norms and customs of a different society belonging to other continent and place. Conrad's stories have a historical setting, and when he wrote his tales, he might well not have been induced by any sort of racial preferences and prejudices. He was a peregrinator, and his characters were mirrored against the backdrop of an experience that was real, poignant and tragi-comic. I am certain that he personally never took upon himself the task of chastising the East through his novels for creating a universal civilization. Had it been so, his western characters in the Chance, Victory or Almayer's Folly would not have followed into the footsteps of grief-ridden African and Asian males and females. No other novelist could make life so much meaningful and worth-chasing through its despair, anguish and misery. For me, Conrad was a master of elevating sorrow to the level of passionate ambition.

Mahmud Hussain is retired Air Vice Marshal and former High Commissioner to Brunei.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments