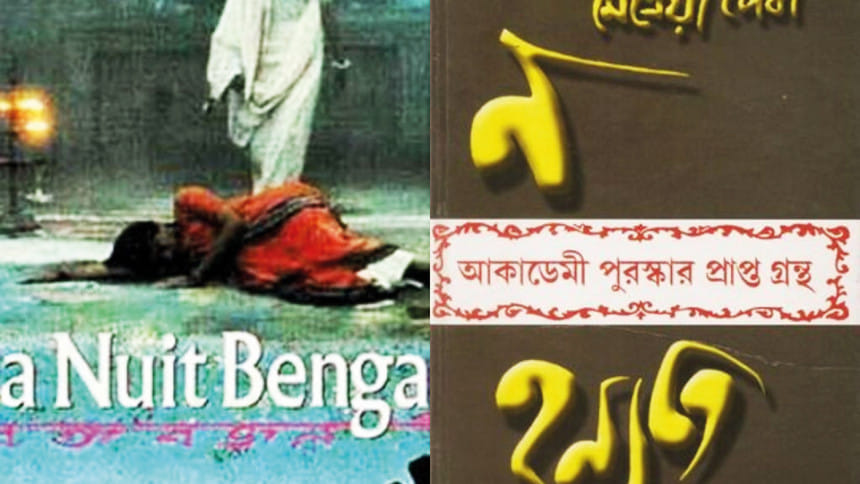

Distance and Togetherness: A Reading of La Nuit Bengali and Na Han-yate

Written forty years apart from each other, La Nuit Bengali (Bengal Nights) by Mircea Eliade and Na Hanyate (It Does Not Die) by Maitreyi Devi are yet two sides of the same coin. While some may call them another version of unsuccessful teenage love, the New York Times described the two novels as "an unusually touching story of young love unable to prevail against an opposition whose strength was tragically buttressed by the uncertainties of a cultural divide." They are pitched differently; one being written as a fascinating and exotic love-story by a young European explorer, the other a mature Indian woman recalling and exploring her own past in response to the fervent tale.

Interestingly, both these narratives have a different development (although having similarity in events) where various discourses force to their separate points of views. The eventual meeting of the two protagonists, their coming together, and departure in the context of their cultural, racial, gender, familial, and regional differences lead to their play of life. Yet among all these dissimilarities, "love" continues to remain the common factor without which the last meeting between them more than four decades later would not have been possible.

These two novels— one published in 1933, and the other more than 40 years later in 1973, in response to the first by two renowned intellectuals retell the story of their love affair from two widely divergent perspectives. These dissimilar points of views work as a catalyst to their "separation." Eliade (1907-1986), best known as a theologian, tells his version of the romance with Devi in a thinly disguised autobiographical novel. While his one is written before his 30s, Devi's, on the other hand, comes around her 60s, at a very experienced and mature stage of life. It is vividly discernible in La Nuit Bengali that Eliade sees in Maitreyi Devi what the West has stereotypically seen in the East: a mysterious pool of spirituality, "irrationality" and sensuousness. And Devi in her rejoinder Na Hanyate (It Does Not Die) goes in contrast to Eliade refuting his claim of physical relationship mainly and his miscomprehension of Indian culture, etiquette and hospitality. She breaks down the West's stereotypical notion about the East and emphasizes the psychological and philosophical union rather than the physical. Additionally, a sort of self-censorship is also seen in her narrative as well which is implicit in her words.

Both novels attempt to recount the identical history of a romance set in the colonial past of India. Both tell the story of an actual, cross-cultural romance that unfolds in the pre-independent period of India. Interestingly, these two textually interrelated documents possess a serious mismatch in the perspectives of the authors. Facts are disputed here most notably whether or not the romance involved physical union or something beyond that attachment. In Devi's recount it is clearly evident that love is not only and simply the physical intercourses; rather love has deeper association with mentality, family, friends, relatives, and society. She in her story says Sergei (A countryman of Eliade who had read his novel):

"If he (Eliade) really was so much in love, why did he run away at one snubbing from my father? Had he no duty towards me? Have you ever known of such cowardice?" (Devi 10)

These lines by Devi and her thoughts on life's fulfillment affirm how much both love and family are important for her. She neither could leave her father, nor be with her beloved. Her education, ideology and philosophy does not allow her to get segregated from her society and culture. These doings and beliefs by Devi substantiate her devotion to Indian mores and values.

It is not unlikely that in a larger context of intercultural exchanges there will be collisions and conflicts. For example, In La Nuit Bengali and in Na Hanyate Western consciousness and its focus on ego (superiority), individuality, veracity and science collide with Indian consciousness and its focus on unity, scholarship, philosophy and truth that makes the collision almost inevitable. For example, when Eliade is told to leave Devi's house, he seems to think that the girl also should bear some responsibilities. But he never hears from her. Devi, on the other hand, feels it is Eliade who has to come forward and assure Devi's family, especially her father in winning her hand. The beliefs also collide in Eliade's general attitude which shows his suspiciousness of Sen's (Devi's father) courteousness and his offer to his young Eoropean pupil to reside with his family. He starts believing that they actually want him as their son-in-law.

Interestingly, the reply from Devi explains this particular gesture as a sample of Mr. Sen's belief of liberal education. He felt that if Eliade resided with them, there would be an opportunity of the exercise of Indian and Western culture together. In addition, Eliade would get a home as he came to India from a far-off country. Moreover, Mr. Sen admired him as he found him to be an excellent learner of Sanskrit. Indian culture certainly did not really invite inter-racial marriage as the young Eliade imagined. Apart from the familial and cultural conflicts, there are some gender and racial clashes which are also found in Eliade's description as if he were rediscovering Indian women and race. Firdous Azim identifies this as the typical western observer positioning himself as an explorer who seems to ascertain the secrets of the "other" world. The woman is seen to be the repository of those secrets, made to open the secret to the explorer. On his first encounter with Devi, Eliade observes, "Her (Devi) uncovered legs, darkish face, crimsoned lips, deep black eyes, and slightly curly hair reminds me (Eliade) of the bohemian girls of our country." Again, the passage following this episode castigates the native for her lack of knowledge of western ways, Devi who does not know where to look.

Finally, age plays a significant role in both narrations. By the time Devi writes her part, it seems to be far more graced with maturity, experience, knowledge, and understanding compared to Mircea Eliade's novel, which is more like a narrative written by an angry teenager decrying the injustice he has suffered. Of course, Devi wrote her version much later and she seems to exonerate Eliade, her father, and her society by glorifying the theme of celestial or platonic love that is beyond physicality, culture, and race reminding us the lyric from Rabindranath Tagore "Tumi robe nirobe hridoye momo."

Abdullah Al Mamun is currently pursuing an MA in Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments