Ray and His Political Films

"Films cannot change society. They never have. Show me a film that changed society or brought about any change," said master director Satyajit Ray in an interview for the American magazine Cineaste more than three decades ago.

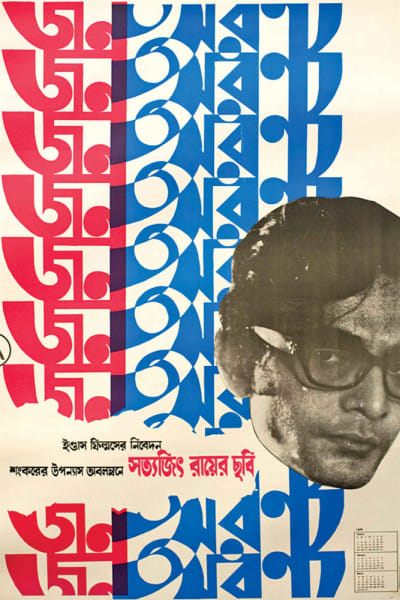

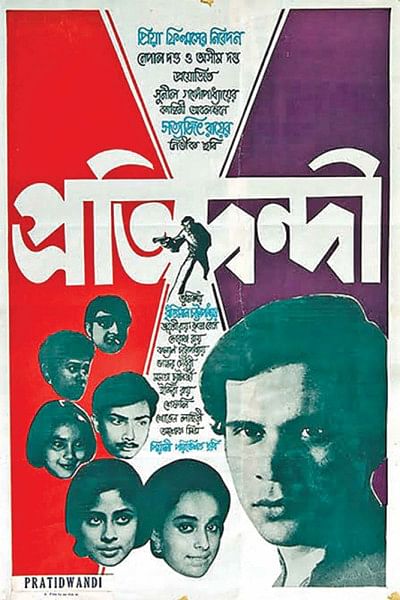

The remarks came from a man who was one of the most politically conscious directors India had ever produced and was never constrained by it. It's a political consciousness derived from the tumultuous years of the Naxalbari movement of the 1960s and 70s and the Emergency in the mid-seventies. It is reflected in Ray's films, such as "Jana Aranya" (The Middleman) and "Pratidwandi" (The Adversary). Later, he returned to the political theme in "Hirok Rajar Deshey" (In the Land of Diamond King) and in a different setting in "Ganashatru" (An Enemy of the People). Ray's "Ghare Bairey" (The Home and the World) also makes a strong political statement in pre-independent India, relevant even today.

While "Jana Aranya" and "Pratidwandi" are rooted in real life, "Hirok Rajar Deshey" is the best political satire couched in a fantasy tale. The three films bring out Ray as the strongest critic of a creaking socio-political system with corruption in almost all spheres of life--education, the corporate sector, bureaucracy, and mass unemployment, leading to moral decay in society. Anyone having seen the three films cannot escape the conclusion that the director was an out and out political product of his time.

"Hirok Rajar Deshey" deals with the fall-outs of a dictatorial regime on different segments of society—workers, farmers, teachers and the poor at large. In the other two films, we see the political statement emanating from the life of urban middle-class families in Kolkata, which become the microcosm of oppressive and dysfunctional political and social setups.

How has a director like Ray conveyed his own political views? There are primarily two ways of finding them out: (1) through changes made in the script to recreate on screen the novels which "Jana Aranya" and "Pratidwandi" are based on and (2) through his interviews. While Ray made many departures from the books that "Jana Aranya" and "Pratidwandi" are based on to enhance the cinematic appeal, there are also some changes in dialogues that reflect his own views than those of the books' authors.

It was surprising how the interviewer of Cineaste magazine of Chicago asks Ray in 1982 if he thought he had avoided making major political statements. More interesting for a student of Ray's films is the answer he gave: "I have made political statements more clearly than anyone else, including Mrinal Sen."

The political climate of the 1970s is manifested from the very opening shot of "Jana Aranya," where mass copying occurs during a college examination in Kolkata. We are shown graffiti on the classroom wall hailing the Naxalite movement (slogans like, "Armed revolution is the only way to emancipation for the proletariat" and "Power comes out of the barrel of a gun") and also a sketch of Mao Zedong. As the film's protagonist Somnath Banerjee, an educated unemployed middle-class youth, walks along the streets in futile search of a job, the camera shows the Naxal movement slogans on the boundary walls of buildings in Kolkata. This scene helped brilliantly recreate the atmosphere in the city during the peak of the Naxalite movement.

The political statement in the film becomes clear early on when Somnath's father learns from his elder son Bhombol about the three young Naxalites being killed in an encounter with the police. The father, a Gandhian, is stunned and responds by saying one cannot muster such courage to die unless motivated by a great ideal. In the preceding dialogue, the father contrasts it with his own time as a student in pre-independence India when they hit the streets against British colonial rule at the call of Mahatma Gandhi. However, they were scared of dying. It is a stark contrast between two political ideals of two different times.

Somnath's father is so drawn to the Naxalite ideology that he asks his elder son to get him the Communist political documents. One sentence from the father sums up beautifully the prevailing socio-economic climate of the time, leaving the youth with two options: "Either you resort to dishonest means and join the rot or join the revolution." Another masterpiece one-liner dialogue from Ray, which sums up the political climate of the day in "Jana Aranya," is when the father hears from Somnath about one lakh applications for ten posts and responds, "it is not without reason that they (youth) are revolting." The word 'Naxal' is never uttered by Somnath's father or any of the film characters, yet even the most naïve person cannot miss the reference.

Years later, we find Ray admiring in an interview the courage of Naxalites. The director is asked by his official biographer Andrew Wilson if he admires the courage of a Naxalite activist like the younger brother in "Pratidwandi." He replied, "Oh yes, I do. Because I don't share that kind of courage—the kind that can face bullets and even lay down one's life. This aspect of Naxalism has always fascinated me. The extraordinary amount of courage that they have – the sheer physical, elemental courage. I don't think I could face a situation like that. One can't avoid admiring such courage." There is little doubt that Ray has put something of himself in what Somnath's father says: "Ora maartey jaane morteyo jaane (They can kill and are ready to die)."

Another illustration of Ray's approach to political issues comes out in the interview with the Cineaste. He said, "You can see my attitude in The Adversary where you have two brothers. The younger brother is a Naxalite. There is no doubt that the elder brother admires the younger brother for his bravery and convictions. The film is not ambiguous about that."

Somnath's father's admiration of the courage of Naxalites in "Jana Aranya" is akin to "Pratidwandi" protagonist Siddhartha's admiration of Vietnamese people liberating their country from American occupation troops. The latter comes out in the interview sequence at the start of "Pratidwandi." Siddhartha is asked in the interview to list the two most important achievements of the last decade, and he places the Vietnam liberation war above man's landing on the moon. Asked by the interviewer why he thinks so, Siddhartha argues that while the moon landing was not entirely unpredictable and had to happen one day, the Vietnam war outcome was a different case. He points out the "extraordinary power of resistance of the Vietnamese people; their plain human courage." The interviewer asks Siddhartha if he is a Communist and his curt reply is that one does not have to be one to admire the Vietnamese people.

"Jana Aranya" begins and ends with shots of decay--moral and socio-economic. We are shown how this occurs in the educational system (mass copying in college examinations and the perfunctory manner in which the examiner evaluates protagonist Somnath's History paper, costing him marks) and in the corporate world and society. Unable to get a job, Somnath turns into a businessman procuring orders and supplying goods. He does not hesitate in using a prostitute, who turns out to be his close friend Sukumar's sister, to seal business deals. Portrayed is a society in which a young woman is forced to sell her body to earn money and sustain a family while her brother struggles to find a job.

Somnath receiving unexpected marks in History (which, according to his father, was his forte) due to the examiner being unable to properly read his handwriting without his power glasses and the father's protests after the result comes out, has an interesting similarity with Ray's personal experience of what happened with his son Sandip. Sandip was also a student of History at the University of Calcutta. We read about this in great detail in "Manik and I" (Penguin, Page 300-302), the memoir written by Ray's wife Bijoya, who said, "I have lost all faith in the modern system of education and examinations after these bitter experiences." There are indications in the book that Ray shared the views of his wife.

The satirical portrayal of Congress MLA Jagabandhu as a politician bluffing the people during a conversation with Somnath and his friend Sukumar is bold by any standard. No party is mentioned in the film, but when the MLA is shown in his chair with portraits of Indira Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru on the wall, one is left to doubt little about the political identity of Jagabandhu. Ray cites this sequence in his interview with the Cineaste to say that, "I have made political statements more clearly than anyone else, including Mrinal Sen. In Middleman, I included a long conversation in which a Congressite discusses the tasks ahead. He talks nonsense, he tells lies, but his very presence is significant. If any other director had made that film, that scene would not have been allowed." Ray was convinced that he had pushed the envelope more than anyone else when dealing with political issues.

The conversation sequence mentioned above involving Somnath's father, Somnath and his elder brother, the dialogues between Jagabandhu and Sukumar in "Jana Aranya" and the interview sequence in "Pratidwandi" are not in the original novels and are totally Ray's creations. They make artistic value addition to the films and reflect a view that resonated widely among a cross-section of people in West Bengal in the 1960s and 1970s. In "Jana Aranya," Ray has packaged a middle-class family's story into what is undoubtedly his best political film by making changes in his script from the novel by Mani Shankar Mukhopadhyay.

Notwithstanding his admiration for Naxalites' courage, Ray's interest as an artist was not on individuals bound by an ideology but on those who are caught in a struggle between ideology and the sheer need to survive in a prevailing political and social system. This struggle is the essence of human drama in "Jana Aranya" and "Pratidwandi." The protagonists would like to revolt against the system but are finally forced to accept it not only for their survival but also for their families.

In "Pratidwandi," the elder brother (played by Dhritiman Chatterjee) revolts on coming to know that his sister's office boss uses her more for her looks than her educational qualifications. He wants to kill the boss but can do it only in his dream. And when he reacts violently in real life against the lack of basic amenities like a fan for candidates waiting in searing heat for a job interview in an office, he loses an opportunity to find a job in Kolkata. Eventually, he accepts a job far away from Kolkata.

In "Jana Aranya," Somnath is gripped by moral qualms when he has to use his own friend's sister as a prostitute to win a lucrative business contract. Somnath tries to prod her to move away on the night he takes her to a hotel to entertain an entrepreneur from whom he will earn the contract. But the woman refuses, and Somnath goes ahead only to return home late that night to tell his father he has managed to win the contract. Ray himself has said in an interview that "Jana Aranya" is his "darkest" film that leaves one with a sense of hopelessness. But it is so realistic that it makes "Jana Aranya" the best political film.

In the interview with Cineaste, Ray, referring to his focus on the elder brother in "Pratidwandi," made it clear that, "(As a filmmaker) I was more interested in the elder brother because he is the vacillating character. As a psychological entity, as a human being with doubts, he is a more interesting character to me. The younger brother has already identified himself with a cause. That makes him part of a total attitude and makes him unimportant. The Naxalite movement takes over. He, as a person, becomes insignificant." The humanist in Ray dominates over the political animal Ray. He was more interested in exploring the human relationships and psychology shaped by circumstances in different layers.

Ray acknowledges the limitations of fighting a deeply entrenched system. "There are definitely restrictions on what a director can say. You know that certain statements and portrayals will never get past the censors. So why make them?" he shared in the Cineaste interview. When asked if he sees the role of a filmmaker as a passive observer or an activist, he pointed to a director's limits in attacking the establishment.

For instance, he pointed out that, "In 'Hirak Rajar Deshe,' there is a great clean-up scene where all the poor people are driven away. That is a direct reflection of what had happened in Delhi and other cities during Indira Gandhi's Emergency. In a fantasy, like In the Land of the Diamond King, you can be forthright, but if you're dealing with contemporary characters, you can be articulate only up to a point because of censorship. You simply cannot attack the party in power," said Ray and recalled how Amrit Nahata's Hindi film "Kissa Kursi Ka" against the Emergency was destroyed. "You are aware of the problems, and you deal with them, but you also know the limit; the constraints beyond which you just cannot go," said Ray in the Cineaste interview.

Asked if he could go farther than he had gone in making political statements, Ray replied, "No, I don't think I can go any farther. It is very easy to attack certain targets like the establishment. You are attacking people who don't care. The establishment will remain totally untouched by what you're saying. So what is the point?" What comes out clearly from Ray's films and the remarks made by him is that, given the kind of political setup in India, there is a limit to which you can take on a deeply entrenched state apparatus.

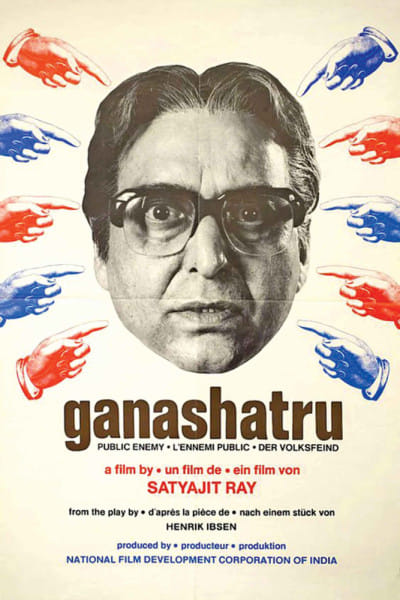

In "Ganashatru," based on Henrik Ibsen's play, Ray deals with religion and politics and how different vested interests in a small town try to resist the scientific outlook of a doctor who is out to prove that the source of water used in a temple is polluted. In the film, the doctor struggles against several adversaries, including his own brother, who is the chairman of the local municipal body, and the editor of a local daily who backs out from publishing his article on temple water contamination. But, as playwright-director-actor Utpal Dutt pointed out, the ending of "Ganashatru" the film, unlike Ibsen's play, leaves you with a sense of hope. That shows how far Ray had travelled from the bleak "Jana Aranya."

In May 1999, political commentator Kanchan Gupta said in an article that "Anandalok" magazine of Kolkata quoted Ray as saying, "I have never found the formula-cast so-called progressive attitudes interesting, valid or of any substance. I always found them an over-simplification…I don't know what Marxism means today – Marxism has changed so much over the years. There's a huge difference between Marx's Marxism and today's Marxism…(Marxism as we see it today) makes me feel as if all doors and windows have been shut…"

As a humanist and a liberal, Ray could never be seen through any ideological prism as he explores layers of human society, emotions and psychology in a given socio-economic setup.

Pallab Bhattacharya is a special correspondent for The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments