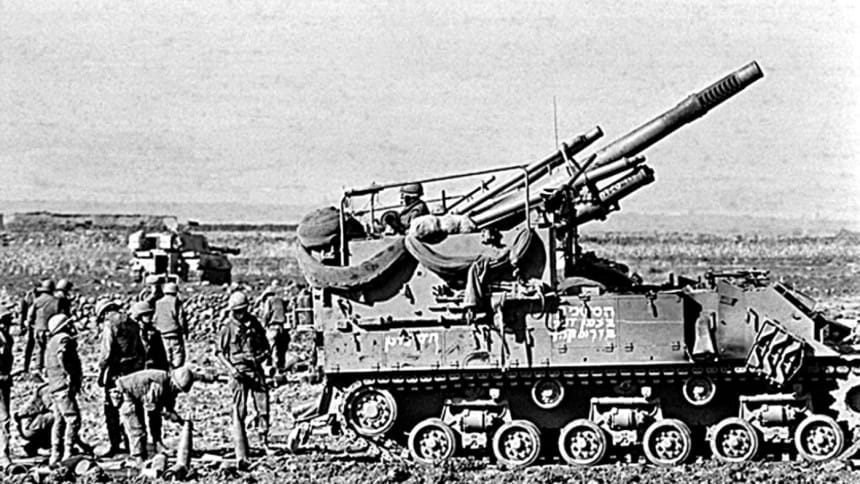

A look back at the 1973 Arab-Israeli War

The 1973 war between a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria against Israel, known alternatively as the Yom Kippur War or the Ramadan War, was fought from October 6 to 25 mainly on Arab territories—Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights—that were occupied by Israel after the Six-Day War of 1967. Although the war itself lasted only a few days, it would be a mistake not to look at it as just one small part of the larger Arab-Israeli conflict that began in 1948 when the state of Israel was initially carved out of Palestinian land—a conflict that still continues in some sense.

Like most conflicts, the Arab-Israeli dispute is a complicated one. And to better understand the war of 1973, one has to look at least six years back.

While there can be no doubt that the Arab coalition started the war of 1973, clever manipulation of history has led many to incorrectly blame Arab leaders also for the war of 1967. A closer examination of the Six-Day War, however, reveals how it was Israel that had set a trap for Egypt's President Nasser and had wanted to start the war of June 1967.

The key to this understanding is the fact that on November 4, 1966, Egypt and Syria signed a Defence Agreement in the hope that it would allow the two to prevent war by discouraging Israel to go on the offensive against either country, knowing that the other would be forced to intervene as per the agreement. It was with this knowledge that Israel began to set its trap for Nasser by provoking cross border shootings with Syria.

The provocations reached their peak on April 7, 1967 when Israeli Mirages shot down six Syrian MIG-21s. This left Nasser with two choices: i) Either to honour the agreement and come to the defence of his ally under attack by Israel, or; ii) To do nothing and lose his credibility as the leader of the revolutionary Arab world—as he was seen to be at that time. When Nasser chose to do the former by putting two Egyptian divisions into the Sinai right next to Israel's border and closing the Straits of Tiran, Israel had their man right where they wanted.

As the Israeli Chief of Staff Rabin explained in an interview published in Le Monde on February 28, 1968, "I do not believe that Nasser wanted war. The two divisions which he sent into Sinai on May 14 would not have been enough to unleash an offensive against Israel. He knew it and we knew it." What that did, however, was give Israel the ammunition to invent "the entire story of the danger of extermination" that it faced "in every detail" and exaggerate it "to justify the annexation of new Arab territory," as Mordecai Bentov, a member of the wartime national government told Israeli newspaper Al-Hamishmar on April 14, 1971.

General Matetiyahu Peled, Chief of Logistical Command during the war and one of 12 members of Israel's General Staff, wrote in an article for Le Monde on June 3, 1972 that: "While we proceeded towards the full mobilisation of our forces, no person in his right mind could believe that all this force was necessary to our 'defence' against the Egyptian threat. This force was to crush once and for all the Egyptians at the military level … To pretend that the Egyptian forces concentrated on our borders were capable of threatening Israel's existence … insult the intelligence of any person capable of analysing this kind of situation."

And, lastly, this is what Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin had to say in 1982: "In June 1967 we had a choice. The Egyptian army concentrations in the Sinai approaches did not prove that Nasser was really about to attack us … We decided to attack him" ("Some Israeli leaders do sometimes tell the truth", Alan Hart, June 3, 2015).

The terrible humiliation that the Arab world faced following the Six-Day War was unprecedented. After the routing of the Egyptian-Syrian-Jordanian alliance, Israel was able to take the eastern part of Jerusalem, including the Old City—with the revered Jewish sites of the Temple Mount and the Wailing or Western Wall, the Muslim Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque, and the Christian Church of the Holy Sepulchre—which added another religious dimension to the longstanding conflict. At the same time, it established Israel as the regional superpower that it is today having acquired land from Egypt (Gaza and the Sinai), Jordan (the West Bank) and Syria (the Golan Heights)—increasing hostilities by bringing large populations of Arab people under Israeli occupation.

It was against this backdrop that the Arabs launched their attack on Israel in 1973. According to military historians, the reasons why the Egyptian president of that time, Anwar Sadat, launched a surprise attack on Israel in 1973 starting the October War, were "to recover all Arab territory occupied by Israel following the 1967 war and to achieve a just, peaceful solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict."

But Israel's inability to predict the Arab attack was not solely down to the Egyptians successfully employing Russian deception techniques stated in its military doctrine of the Maskirovka. It was also because Israel thought that Arab military capabilities could not match its own after the Six-Day War, at least not as quickly—despite intelligence information and warnings that Egypt was preparing for war.

The Arabs in the war of 1973 did not intend to deal Israel a major blow nor liberate Palestine, as was the case with previous wars, which meant that the often-propagandised danger of Israel facing annihilation by combined Arab forces was not present, at least not during the initial phase of the war. Egypt wanted to "breach the Bar Lev Line and retake territory across the Suez Canal," while Syria "hoped to retake the Golan Heights that it lost to Israel six years earlier" ("The Arab-Israel War of 1973 and its legacy", Centre for Research on Globalisation, October 9, 2017). As the objective of both the major Arab countries in the war were simply "to restore some degree of Arab pride and to use the war as leverage to negotiate the return of occupied land by Israel," it confused Israel as to how to react in the early days of the war.

Moreover, having been taken by surprise, Israel needed time to mobilise its armed forces, which is what allowed the Arab coalition to have great success in the beginning of the war. That success, however, did not last long as Israel soon managed to push both sides back substantially before the war was ended through two ceasefires.

The first ceasefire was largely negotiated between the US and the Soviet Union and passed 14-0 at the United Nations Security Council on October 22 through Resolution 338. However, it failed to hold for long with both sides blaming each other for the breach. As hostilities commenced once again the Israelis managed to simultaneously improve their position and encircle Egypt's Third Army and the city of Suez by October 24. This escalated tensions between the Soviet Union and the US with both sides fearing intervention from the other. This fear fortunately led to a second ceasefire being imposed cooperatively on October 25, which finally managed to end the war with both sides claiming victory.

Though the initial success of the Arab coalition led to a deterioration in the perceived cloak of invincibility among members of the Israeli armed forces according to Israeli military experts, the final outcome of the war also led to the disintegration of Arab unity to a large extent. After the signing of the 1978 Camp David Accord as a result of the Yom Kippur War, Egypt finally managed to get back its territories occupied by Israel but Syria didn't—even till today.

The Accord also resulted in the Egypt-Israeli Peace Treaty, the first ever between Israel and an Arab state, which outraged many in the Arab world and led to Egypt being suspended from the Arab League until 1989. Until then, Egypt was seen as a leader of the Arab world, but its peace treaty with Israel ended such perceptions and, two years later, on October 6, 1981, President Sadat was assassinated by Islamist army members who were enraged at him for negotiating peace with Israel.

Another important takeaway from the war was that it had once again brought the world to the brink of World War III and, possibly, a nuclear war. After the war, the Soviet Union claimed to have deployed Scud missile brigades armed with nuclear warheads to assist its Arab allies, while Israeli Defence Minister Moshe Dayan is said to have ordered the preparation of at least one ballistic missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead.

In his book The Sampson Option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy, Pulitzer Prize winning author and journalist Seymour Hersh wrote that Israel's message to the administration of President Richard Nixon requesting an arms airlift was accompanied by the threat of deploying nuclear weapons onto the field. And although the Americans wanted to pursue a more restrained approach according to some Israeli political insiders, it is an established fact that "the US placed its Strategic Air Command, Continental Air Defence Command, European Command and the Sixth Fleet on DEFCON 3 alert because of fears that the Soviet Union might intervene in the conflict on the side of its Arab allies."

Unfortunately, that spectre of nuclear war is yet to be removed from the Middle East as the Palestinian West Bank and Syrian Golan Heights still remain under Israeli control and as Israel continues to violate Syrian sovereignty by constantly attacking both civilian and military positions in its neighbouring country. And the stubbornness with which Israel refuses to respect its neighbours even now is arguably an extension of its arrogance to reject a regional peace agreement that was quietly offered to it by the Arab League only a few weeks after the end of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, as disclosed by WikiLeaks through the disclosure of classified US diplomatic cables from that period.

Which is why, understanding the Yom Kippur War and the events that led to it are still so important. As the conditions that pervaded the Middle East at the time is nearly identical to what currently exists, posing constant threats of World War III and a nuclear war for the world in its entirety.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. His Twitter handle is: @EreshOmarJamal

Comments