Is democracy possible?

Discourse on democracy is so overwhelmingly taken for granted that even the blatant autocrat or invader claims to act in the name of saving or installing democracy. Yet, it stumbles, and often awfully – raising doubts of its universal applicability free from context and condition. This is a brief attempt to explore why it falters in view of its evolution and practice.

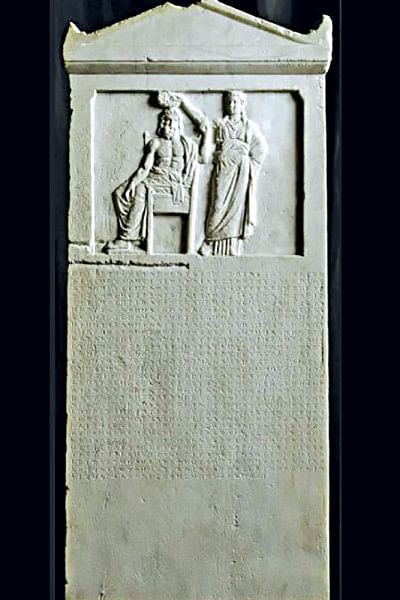

Grownup Democracy

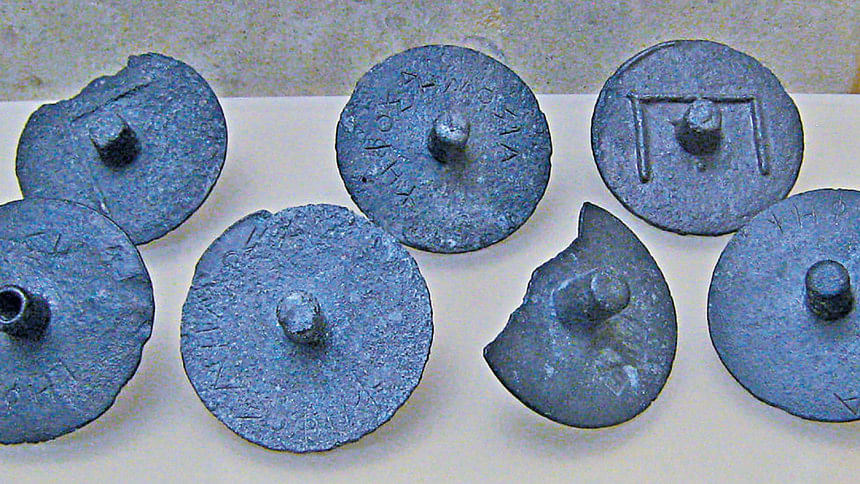

The present form of representative 'democracy' is relatively a recent phenomenon; starting only after the series of revolutions in Europe and America in the 18-19th centuries. In the wake of massive socio-political upheavals the hitherto feudal order and all the trappings that come with it were turned topsy-turvy, or discarded, or diluted in varying scales in different societies. People from different walks of life had participated in these popular uprisings. Naturally all claimed a stake in the pie. But the wealthier classes wanted to preserve their wealth while the subalterns sought redistribution. The former, small but powerful, kept the vote to themselves. Universal suffrage was still more than a century away. Democracy early on got rigged in favour of the wealthy by deploying any devious means necessary. This conflict of interest wouldn't go away but has been managed since, which however was not at all peaceful.

It was carried out by the state with the infamous 'blood and iron' tactic while providing bare survival wages to the workers that too after persistent agitation (Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital). It's a story of heart-wrenching realpolitik, devoid of any morality. It was a long protracted battle of nerves fought in the streets, chambers and parliaments of Berlin, Paris, London, New York, Chicago and other big cities of the western world all during the 19th century, culminating in World War I. Eventually a bargain was reached to maintain a working relationship. The wealthier classes will govern, the working classes would get the right to vote, 8-hour workdays, safety at work, right to strike, demonstrate, and few social security benefits, emancipation from slavery (E P Thomson, Making of the English Working Class). But women got to vote much later. All these must have cost a lot of money. Who footed the bills?

In comes the colonial project. Yes, the renaissance, the reformation, the revolutions, and above all the capitalist thrift were the creators of the western democracies but they were sustained by the colonial pillage. Systemic genocide of the Red Indians, their stolen land, and slavery paid for the American democracy, while the Afro-Asian colonies bankrolled the European ones. This is vital evidence these widely admired and so-called mature democracies graduated by demonising the colonies. In this project the working classes were co-opted by their capitalist rulers (M Beaud, A History of Capitalism). So, democracy evolved as a social contract between conflicting classes. And in the process got locked with capitalism in a perpetual battle over who will control whom and how much. This process was sustained by regular colonial wars.

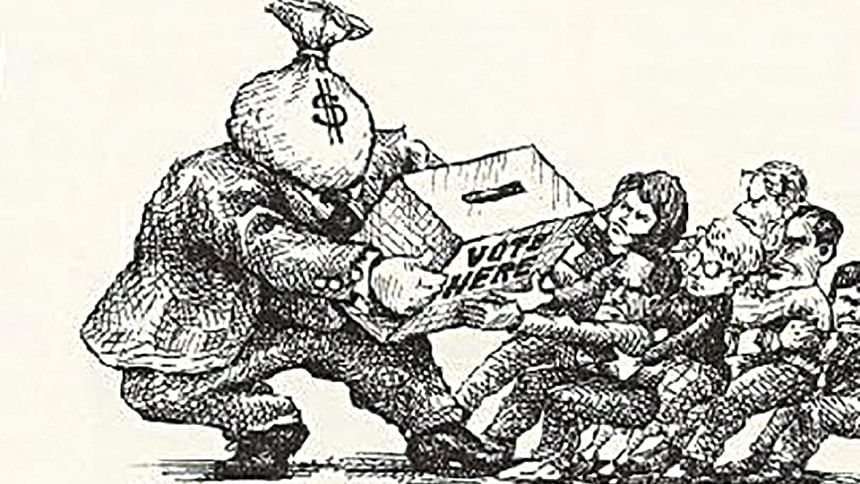

These wars were meant to create captive markets for supply of raw materials and sale of finished products of the industrial world. Gradually, one East India Company gave way to dozens of similar but far more powerful multinational companies, which grew to control the world's economy and finances. Their global reach was phenomenal; they virtually dominated respective governments. And they did it by controlling the political parties. A visible functional democracy is alive alright, but the key decision-making power that influences the lives of the majority of the electorate is no longer controlled by the parliament or the Congress.

That's been silently taken over by a plutocracy: a collective of powerful bankers, industrial barons, media owners, generals, and bureaucrats. To this power centre, public participation in the decision-making process is a nuisance (Chomsky & Herman, The Washington Connection and the Third World Fascism). This is affirmed by the last speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow, "The parliament has become a cross between a rubber stamp and a talking shop." In a recent interview published in The Independent, a US voter said, "…the candidates are chosen by the DNC or RNC despite popular opinion (we saw this with the DNC essentially staging a coup against Bernie), and with systems in place such as voter suppression, polling place closures, redlining; it isn't a fair system to begin with, and it's designed to give the illusion of democracy."

It's for the gain of the plutocracy the western states once embarked on the colonial project and presently control the global order. This demands a constant war footing that makes them grow into national security states. Since most people have no stake, the media is deployed to create war hysteria by manipulating public opinion. The whole system is rigged in favour of the rich and the powerful. Transparent periodic elections are held, faces change, but imperial policies remain the same. Democracy has become a public relations exercise.

All the trappings of a free, fair and open society exist in varied scales but an invisible boundary also exists that must not be crossed by ordinary mortals. The inner wheel of this power centre is anything but open, democratic, or accountable. Anyone daring to cross that line is branded traitor and treated like Assange, Snowden or Chelsea. It couldn't care less about public/world opinion or any rules/regulations. Its will must prevail at any cost. It goes on exerting global influence by diplomacy, finance, or when necessary flexing muscle. This is what the West (G7) dominated post-WWII neoliberal world order is all about, enforced by NATO and the US military machine. After the Soviet implosion it has simply gone berserk. In the colonial days, the excuse was the white man's burden to civilise the world, in present day its democracy, human rights, international law, crimes against humanity and what not – none of which apply to G7 states. But in the developing states they are carried out by media vilification, sanctions, financial squeeze, curbing market access, regime change – and when all fails military invasion. G7 expects the world to recognise this double standard as the international rule of law.

Growing Democracy

Under this prevailing neoliberal global order the entire developing world is struggling to make ends meet. The rigour, discipline, and tolerance for diversity and dissent required to nurture a democratic society are at best proving extremely arduous, at worst, unattainable. Why so? In the wake of decolonisation, the conventional wisdom was the wheels needn't be reinvented, just fitting them in the new states would create suitable conditions and the rest would take care of itself. Little did this simple logic realise the same wheels cannot run in roads with regional or climatic variations. What this logic did not appreciate was democracy was not a gift from the sky to the western states. It was earned through blood, toil and tears, through societal upheavals lasting over a century in some cases. Yet most of the post-colonial states opted for the western form of democracy already at a mature stage. Did they choose wisely? Here is the tricky part.

Nearly all desired to be nations, but where are they? The social contract between diverse classes, ethnicities and religions – the essential requisite of growing into a nation – was absent. The very idea of being a nation was confined to a tiny but powerful educated elite. Yet they claimed to represent the diverse components and strived to create nation states. Apparently, it may look odd, but if one cares to look at how all colonised people through history responded to their imposed conditions, this fits into a general pattern. They first resisted, then with time some among them quickly, some slowly, had adopted much of the cultural, socio-political views and in many cases also the faith of the colonisers. So when the European colonisers spread across the world for the past 3-4 centuries, they too left their mark on the colonised people. However, in this case the adopted European socio-political and economic constructs were completely different from any hitherto practices that prevailed earlier in these colonies. Yet, the catching up syndrome was the overriding driving force of the elites to prove their worth.

Thus, all the institutions of democratic governance were installed but the heart and soul of democracy i.e., the social contract between multiple components, was missing. The earlier socio-economic conditions had to be replaced by creating new ones which in most cases were alien in the post-colonial states. For example, democracy requires recognition of individuals as sovereign and expects one to make an informed choice by oneself. This was never the case in the colonies; the clash between tradition and new form of control was unavoidable. This became a common trend whether in Latin American states which gained independence during the 19th century or the Afro-Asian ones that gained theirs from the mid-20th century. Consequently, nearly all needed to create nations out of whatever the tiny elite imagined it to be which, however, remained contested. Moreover, they soon found out their independence did not give them the choice to pursue independent policies whether at home or abroad. Except very few, economies of all the post-colonial states were integrated with the prevailing global neoliberal capitalist order under the firm control of the erstwhile colonial states. The new ones had no choice but maneuver whatever little space they could create within this structure. The little they achieved was mostly because of the Cold War, but was controlled by the few instead of the many.

Interacting with the imperial centre represented by the multilateral financial institutions, the UN bodies, and the MNCs had benefits as well as costs. It offered global connectivity, access to credit and market, and recognition as an independent entity bringing some diplomatic leverage. But the cost proved huge. The new states had to abide by the stiff rules, regulations, and strings tagged with every benefit they availed. Thus began the economic control that gradually created conditions for political control as well. Caving in to these controls and yet uphold democratic governance, or meet the endless demands of the vast majority of ordinary people, proved hopeless. Soon in quick succession nearly all the new states restored autocratic governance whether of the left or right variety, in khakis or civvies, with or without a parliament. The last remaining hope of creating a democratic society in a developing world was India. But after three quarters of a century it too seems to be rapidly and irreversibly sliding into autocratic governance. This of course was in the making for some time. Arundhati Roy observed, "Tidal waves of money crash through the institutions of democracy—the courts, parliament as well as the media, seriously compromising their ability to function..." (Outlook India, April 9, 2012).

However, within this constrained condition some of the states did attain economic success and a reasonable level of political stability. But even in such few bright cases where they do have functional legislatures, the real levers of power are held by unelected corporate bodies (public or private). By and large the general trend across the developing world is concentration of wealth in fewer hands. In every state a new breed of 'Nabobs' has cropped up; in absence of colonies they loot the exchequer. This in turn leads to regression, repression and finally creates the national security apparatus. The state agencies, the people associated with them or the MNCs, big businesses, or other donor agencies benefit immensely while most of the people are deprived of a decent livelihood. Crime syndicates run amok. Hence, a regular state of tension prevails across the entire developing world.

Where does democracy or rule of law fit into this scheme of things? The organic nature of democratic/participatory governance has slowly but surely eroded in the West over the past several decades. In the developing world the absence of the organic birth of democracy coupled with predatory neoliberal capitalism makes a mockery of democracy. But it's a sin to give up hope. The need is to explore alternatives and strive for improvement.

Ali Ahmed Ziauddin is a researcher and activist.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments