HIS PICTURES SPEAK A THOUSAND WORDS

In this region, the history of garments production is age old, and so is the struggle of those who stitch the garments. There was a time when we created fabrics which made our region popular all around the world. The fingers of workers would be cut off so that they couldn't replicate their “masterpieces”, thus becoming mere slaves to a perverse system of hierarchy. In this era we get to see a modern form of slavery. The fate of the oppressed has not changed, but the show goes on. Even on festivals like Eid, garment workers are forced to carry on with sewing and stitching fabrics to meet the demands of buyers. The struggle of garment workers is therefore not new; over the years, this struggle has become a part of our history, our heritage, passed on from one generation to the next.

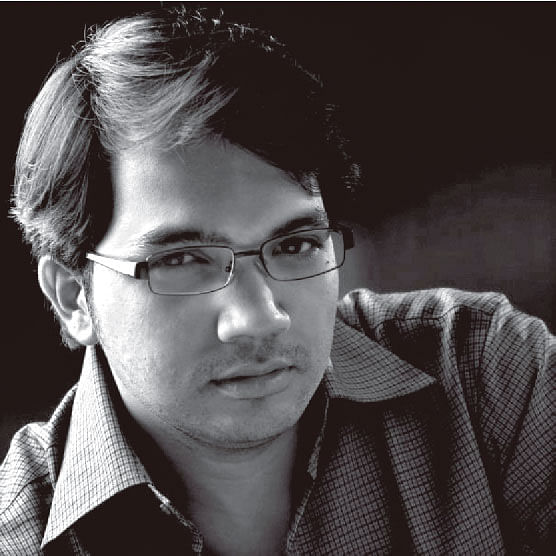

Internationally acclaimed photographer Andrew Biraj's photo exhibition 'Bonded Stitches and Struggles' forces us to revisit the horrors inflicted on the people responsible for making Bangladesh the second largest garments exporter in the world. Biraj, who holds an advance diploma in photography from Pathshala, the South Asian Institute of Media Academy, and a BA in Photography from the University of Bolton in UK, believes that it is time to give workers the space and scope that have been denied to them all these years.

Your exhibition is named 'Bonded Stitches and Struggle.' What is the reason behind choosing this name?

Workers in the garment industry do their job while grappling with a constant fear in their hearts. They are basically slaves to their work and their employees. They don't have any freedom to live a life outside their job. The recent pay appraisal for garment workers, from Tk 3000 to Tk 5000 a month, is claimed by many to be the most drastic wage increase in the world. But you see, the employer who says that they have achieved a pioneering feat by increasing the wages of his workers belongs to the society which controls the markets from which these workers purchase their daily necessities. Even the rent that they have to pay for their tiny apartments is controlled by the privileged society. While it's certainly true that there has been an increase of Tk 2000 in their wages, workers are not being able to enjoy the increment. They are thus bonded by financial as well as social and economic constraints. They can't return to their villages, leaving their hellish life behind whenever they want to, they can't just move up the social ladder because there is no improvement in their living standards, they can't even think about feeding their kids a couple of eggs every week because where is the money to do that?

Did you think of focusing on the role of garment owners and international buyers in your photographs presented in this exhibition?

I have tried to focus on the events surrounding the garments industry from the angle of a photo journalist. And thus, I wanted to present the basic reality of this industry to the spectators viewing this exhibition. The portrait of the garment industry that has been etched into the minds of the country's middle class is a reflection of the Rana Plaza incident. Ironically, however, even before the Rana Plaza disaster, there have been countless such incidents that have wreaked the lives of workers but nobody paid much attention to them at that time. These incidents might not have been as visually compelling or moving as the Rana Plaza disaster, because the number of casualties was not as high. Unfortunately, incidents such as sexual, physical and psychological harassment have been a regular part of the garments industry. A girl was thrown off the terrace of a factory, someone else was beaten to death but these incidents were ignored. They just remained snippets of the daily newspaper, and warranted a glance or went unnoticed. Just think of the incident at Hamim Garments where hundreds of employees were killed in a fire accident. You don't even hear of this incident anymore; the public seems to have forgotten that such an incident ever took place. We were shaken and stirred to take action by implementing “building safety” and being “compliant” to international standards only after we faced a disaster that took over a 1000 lives. The oppression of workers is not just limited to unsafe buildings or working environments, it goes way beyond that.

My purpose behind this exhibition was to remind people of unforgotten atrocities, to make them aware that such incidents have become a part of our history. We could not include the perspective of garment employees in this exhibition because of curatorial complications but as this is an ongoing project, I intend to bring their angles to light as well.

You are right in saying that the Rana Plaza incident has created such a discourse that whenever a garments related incident takes place in the country, we give the example of Rana Plaza or think about collapsed garments factories. Do you think that the conversations surrounding the said disaster have overshadowed other major atrocities or incidents that wreak the garments industry?

Of course, it does. Building safety and factory compliance are obviously necessary concerns but other important issues have inadvertently been suppressed under the Rana Plaza incident. It has become a kind of strategy to make people forget about other equally important issues. After a year of the Rana Plaza collapse, we are still talking about compensating victims and their families, as they are yet to get their dues. At this point, it is of utmost importance that the victims are compensated fairly and without further delay. But the problem is that human beings have poor memories; currently, we are talking about compensations, soon we might forget about the issue of building safety, and later in the day, the issue of compensation will also be brushed under the carpet and erased from our memories. Unfortunately, we are not being able to look at long term solutions or to focus on the plight of garment workers as a whole.

You have organised three exhibitions – one at Drik Gallery in Dhaka, one in Savar and one was a street exhibition. Why organise the same exhibition in three different places?

From the beginning, we were clear about holding open exhibitions at least two places, one in Savar and one at the Chhobir Haat in Dhaka University. When photographers hold exhibitions, these exhibitions are mostly attended by a small section of the people living in the city. Our pictures get international attention. But the people who are the subject of these pictures never get to see the creations that they inspire. I felt that it was necessary for me to take these pictures to those people, as they gave us access to their lives; they allowed us to capture their reality in camera. This was a small way to pay respect to their courage. As a photographer, I felt that these pictures should not be limited to the middle class or the educated society; I didn't want the workers to be just mute subjects of these photographs. I wanted them to be a part of the exhibition, to know that their voices are being heard, and their stories are being told.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments