How did Pahela Baishakh become a public celebration?

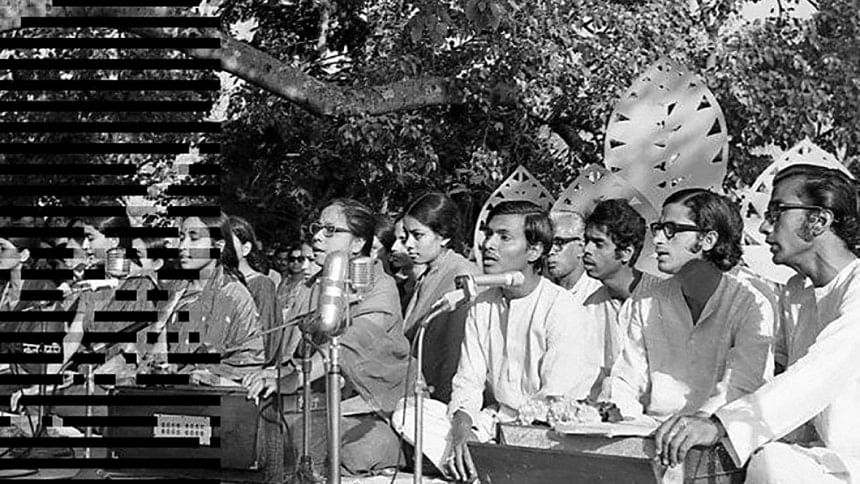

Although the Bengali calendar has been in use for centuries, the tradition of celebrating Pahela Baishakh as a public festival is a relatively modern development. The vibrant festivities at Ramna Batamul—first organised by Chhayanaut in 1967 during the Pakistan era—have become a defining feature of the New Year's celebration and a powerful symbol of Bengali cultural identity. However, the roots of Pahela Baishakh as a collective, civic expression stretch further back. One of the earliest organised celebrations was held in 1951, shortly after the formation of Pakistan. It was initiated by the cultural organisation Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish, with the active involvement of prominent educationists, artists, and journalists committed to preserving and promoting Bengali culture.

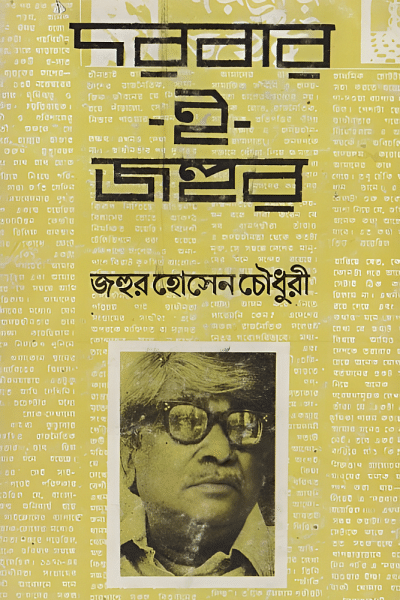

Editor and journalist Zahur Hossain Chowdhury (1922–1980) offered a vivid account of the event in his book Darbar-i-Zahur. He recalled that in 1951, the organisers of Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish decided to mark Nababarsha for the first time at the Mahbub Ali Institute, located at 7 Hare Road in Wari, Dhaka. A cultural performance was held in the evening. Although the arrangements were simple and the stage decoration modest, the event attracted a large crowd—an early sign of public enthusiasm for such celebrations. They printed a receipt book and collected donations ranging from one to five taka through a grassroots crowdfunding effort. He remembered that the total amount collected was 700–800 taka, a significant sum at the time. This also underscores the many people who contributed to the event and expressed their support.

Zahur Hossain recounted an incident when they went to collect funds for organising Pahela Baishakh from Mahmud Hossain, then the Director of Publicity for the East Pakistan government. During their visit, Wazir Ali Sheikh—an ICS officer and the Excise Commissioner, hailing from an elite Punjabi family—was also present in the room. Upon hearing the purpose of the fundraising, Wazir Ali Sheikh remarked dismissively, "Baishakh is celebrated by the Sikhs." In response, Zahur Hossain and his companions firmly replied, "This is our Nababarsha. We don't need to know whether the Sikh community observes Baishakh. Moreover, the Bengali calendar was introduced by the Mughal rulers for agricultural purposes." Despite their explanation, Wazir Ali Sheikh remained unconvinced—an attitude that, as Zahur Hossain noted, reflected the broader indifference and cultural disconnect of the ruling Pakistani elite toward Bengali identity and traditions.

During the celebration of Nababarsha in 1951, Zahur Hossain noted that, among others, Munier Chowdhury, Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta, and Mofazzal Haider Chaudhuri were present on stage. Though not politically affiliated, their participation stemmed from a commitment to promoting Bengali culture on the occasion of Nababarsha—a gesture that symbolised the early stirrings of a search for Bengali national identity during the Pakistan era. Significantly, this celebration took place before 21 February 1952—the historic day of the Language Movement, widely regarded as the starting point of Bengali nationalism. Zahur Hossain wrote that every time Pahela Baishakh was observed, he remembered these three prominent intellectuals—participants in the early cultural initiative that marked the first public celebration of Bangla Nababarsha—who were later martyred during the Liberation War in 1971.

It was Mofazzal Haider Chaudhuri who, in 1953, wrote an article in The Millat advocating for Pahela Baishakh to be recognised as a public holiday—an issue notably missing from the United Front's renowned 21-point demand. The holiday was only granted after the Liberation War.

In his memoirs, Professor Anisuzzaman reflected on the role of Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish in shaping his cultural engagement, which deepened after he moved to Dhaka. He also referred to earlier cultural organisations such as Pragati Lekhak Sangha and Pragati Lekhak o Shilpi Sangha, which struggled to sustain their activities under Pakistan's repressive regime. After their decline, a new organisation emerged with Qazi Motahar Husain as president and Sardar Fazlul Karim as secretary. However, following Sardar's incarceration, its activities came to a halt, paving the way for Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish to take its place. Anisuzzaman noted that Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish likely came into being around 1949, and that cultural figures like Qazi Motahar Husain, Ajit Kumar Guha, and Amiya Bhushan Chakrabarty were regular participants in its programmes.

Anisuzzaman recalled that Amiya Bhushan Chakrabarty, a professor in the English Department at Dhaka University, served as the secretary of Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish and was known for translating many poems by Kazi Nazrul Islam. However, he could not recall who served as the president of the organisation.

Zahur Hossain Chowdhury mentioned that Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish also initiated the celebration of 25th Baishakh, alongside Pahela Baishakh, in East Pakistan. Anisuzzaman added that the birth anniversary observances of Tagore and Nazrul were primarily organised by Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish, which also frequently held events commemorating the birth or death anniversaries of poet Iqbal. He recalled being deeply moved by Munier Chowdhury's recitation of the poem Sadharan Meye during the Tagore birth anniversary celebration organised by Lekhak-Shilpi-Mazlish in 1950.

Reflecting on the first Nababarsha celebration in 1951, Zahur Hossain recalled a moment when a six-year-old girl performed a dance during the event. A literary journalist later criticised the performance in a newspaper, calling it vulgar. Nevertheless, Zahur Hossain highlighted the event's lasting impact, noting that it inspired Pahela Baishakh celebrations in other places.

In a candid reflection in 1979, Zahur Hossain admitted that the celebration of Pahela Baishakh in 1951 was not conceived with the idea of an independent Bangladesh in mind. Instead, it emerged from a desire to assert Bengali identity and preserve cultural expression within the confines of the newly established Pakistani state. Yet, as Pakistan increasingly sought to suppress Bengali language, culture, and political aspirations, these early acts of cultural assertion gradually evolved into a broader resistance—ultimately paving the way for the creation of Bangladesh.

Priyam Paul is a researcher and journalist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments