A counter-narrative of ‘Meghnad’: Reflections on Kabir Ahmed Masum Chisty’s exhibition

As I walked into Kalakendra in the capital's Lalmatia area, I was unsure what to expect from Kabir Ahmed Masum Chisty's solo exhibition, "Meghnad Badh", curated by Lala Rukh Selim. I did not personally know the artist or his body of work, yet I was drawn to the premise—a visual reimagining of "Meghnadbad Kabya", Michael Madhusudan Dutt's magnum opus that transformed the perception of a character largely dismissed in the mainstream "Ramayana". What struck me most was the exhibition's engagement with what Sibaji Bandyopadhyay, in his book "Three Essays on the Ramayana" calls 'dispersed textuality'—the idea that an epic exists not as a singular, authoritative narrative but as an intricate, layered text that absorbs contradictions and alternative voices.

Madhusudan's "Meghnadbad Kabya" itself was a monumental subversion of the "Ramayana". Instead of glorifying Rama and the triumphant devas, Madhusudan centred his work around Meghnad, Ravana's son, portraying him not as a villain but as a tragic hero. The epic, written in amitrakshar chhanda (blank verse), was radical both in form and content. Where Valmiki's "Ramayana" frames Rama's victory as divine justice, Madhusudan presents Meghnad as a noble warrior wronged by fate, challenging the very foundation of dharma (righteousness) as dictated by the epic tradition. The poem does not merely invert the moral structure of the "Ramayana"; it exposes the power dynamics at play, showing how narratives are shaped by those who hold the power to tell them.

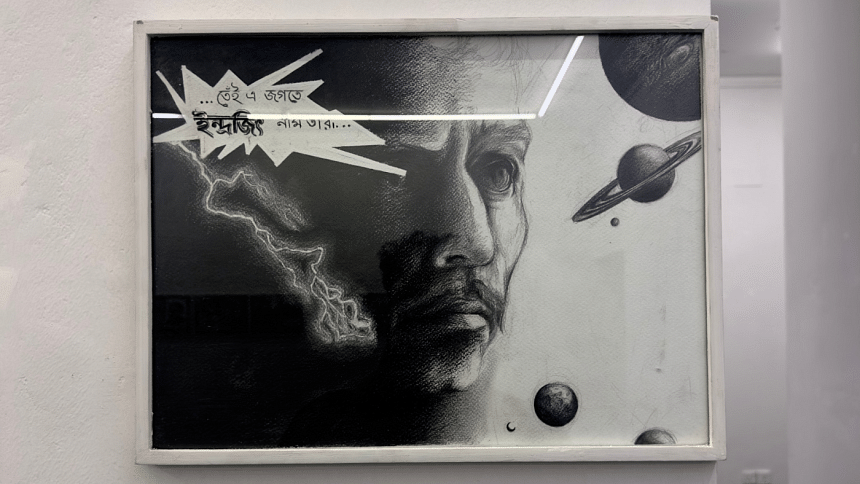

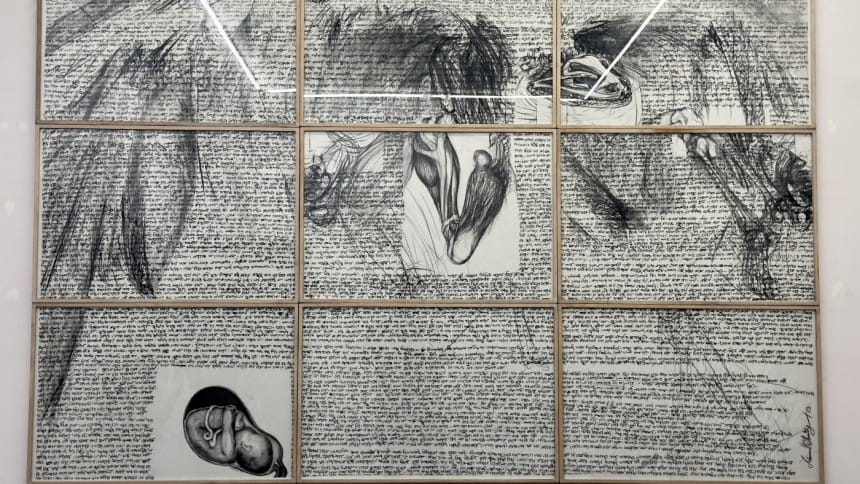

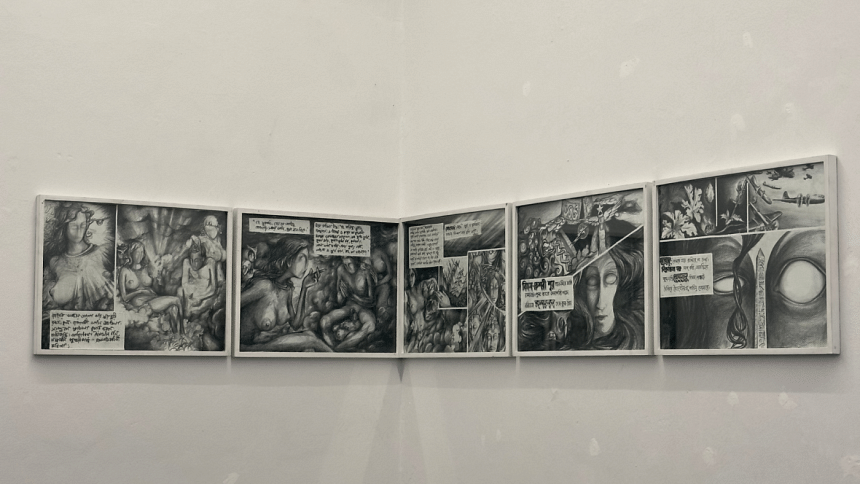

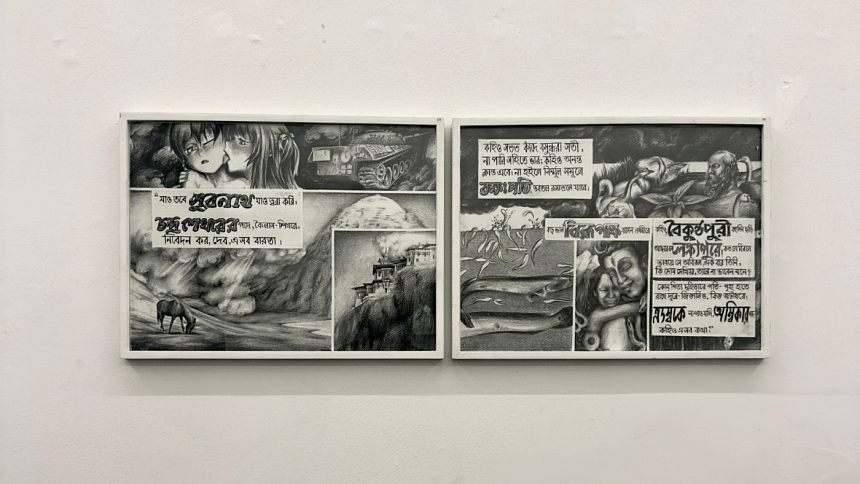

It was in this context that Chisty's "Meghnad Badh" resonated with me so deeply. His work visualised Madhusudan's counter-narrative through an aesthetic that, much like the text itself, refused to be confined to a single style or medium. The artist's use of monochromatic collage immediately caught my attention. Instead of a straightforward pictorial representation, he created a layered, almost fragmented composition where figures, text, and abstract forms interacted dynamically. The effect was striking—Meghnad's tragedy was not just told but visually deconstructed and reassembled, as if to remind us that history itself is an unstable construct.

At the heart of Chisty's engagement with "Meghnadbad Kabya" is a deep awareness of its liminality—both as an epic and as a transgressive retelling. Sibaji Bandyopadhyay, in his critical explorations of the "Ramayana", has emphasised the multiplicity of voices and ideological ruptures within retellings of the epic. Madhusudan's work itself served as a radical inversion, elevating the vanquished 'demon' prince Meghnad to tragic heroism, thereby unsettling the traditional "Ramayana" framework. Chisty extends this subversion by incorporating visual motifs from the 'hybrid world'—a universe where elements from manga, cosmic imagery, and fragmented postmodern aesthetics intersect. His approach reflects what Bandyopadhyay describes as the 'dispersed textuality' of epics, where multiple layers of narration exist simultaneously and often contradictorily.

Furthermore, Bandyopadhyay has pointed out that every counter-narrative exists in negotiation with dominant narratives, sometimes even reinforcing them in unintended ways. While Chisty's exhibition boldly reimagines "Meghnad Badh", it is essential to consider whether his visual grammar challenges the epic's transgression or merely aestheticises it. Does it question the ideological legacies of the "Ramayana", or does it nostalgically retrieve Madhusudan's subversion without contextualising it within today's sociopolitical discourse? These are questions that discerning viewers must grapple with as they navigate Chisty's Meghnad—the demon prince whose voice, though amplified through art, still seeks justice in a world reluctant to hear him.

Chisty's catalogue, printed in the manner of "Mangal Kavya" or old manuscript scrolls, reinforced this hybridity. It was an artistic decision that did not merely evoke nostalgia but also functioned as a critique of textual permanence. In many ways, this tied back to what Bandyopadhyay discusses regarding epics—their supposed fixity is an illusion, as they are constantly rewritten, reinterpreted, and challenged. This idea of dispersed textuality, where multiple narratives exist simultaneously, found its visual counterpart in Chisty's work. His compositions, teeming with disparate yet interconnected elements—manga imagery, cosmic motifs, and textual fragments—evoked the very tension between tradition and disruption that defined "Meghnadbadh Kabya".

From an art-theoretical perspective, Chisty's work demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of collage as both a medium and a conceptual framework. Collage, historically associated with modernist fragmentation, became a tool of narrative resistance in this collection. The deliberate use of black and white intensified the contrast between text and image, enhancing the sense of historical layering. The interplay of graphic montage and gestural brushwork revealed an awareness of both print culture and expressive abstraction, making the work oscillate between controlled precision and emotive spontaneity. In this regard, his approach reminded me of the works of artists like William Kentridge, whose charcoal animations similarly blur the line between history, memory, and artistic intervention.

As I moved through the exhibition, I found myself reflecting on the nature of counter-narratives. Madhusudan's Meghnad was revolutionary in the 19th century, but what does his tragedy mean in 2025? Chisty's interpretation felt less like a direct political statement and more like an existential meditation on historical voices—the ones we elevate, the ones we suppress, and the ones we are yet to hear. Unlike Madhusudan, who sought to challenge the colonial and Sanskritic literary establishment with his poetic choices, Chisty seemed more interested in the gaps, the absences, the distortions that history leaves behind.

This raises an important question: Does an aesthetic of hybridity alone suffice in a time when counter-narratives themselves risk becoming commodified? As Bandyopadhyay points out, every counter-narrative exists in negotiation with dominant narratives, and sometimes, they end up reinforcing the very structures they seek to dismantle. While Chisty's work successfully disrupts linear storytelling, I wondered if it also risked aestheticising the subversion, making it more palatable rather than confrontational.

Nevertheless, the exhibition left a lasting impact on me. It reminded me of the power of reinterpretation—not just in literature but in visual art, where form itself can become a site of resistance. It also made me reconsider the role of the artist in engaging with canonical texts. Chisty did not merely illustrate "Meghnadbadh Kabya"; he reanimated it, breaking it apart and piecing it together anew, much like Madhusudan had done with the "Ramayana" over a century ago.

As I stepped out of the gallery, the images lingered in my mind—Meghnad, fragmented yet defiant, his story still unfolding in the ever-expanding discourse of art and history. Whether or not Chisty's "Meghnad Badh" achieves what Madhusudan did with his text is a question for time to answer. As a viewer, I left with a renewed appreciation for the act of artistic reinterpretation, the courage it takes to challenge received narratives, and the realisation that— in art, as in epics— no story is ever truly complete.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments