The man who won the world: An afternoon with Kumar Bishwajit

My Uber takes me to a nondescript apartment building in Uttara. Closed gates, covered cars; a playful dog inside who greets me with jumps and kisses. I walk through the door and am immediately transported. A magnificent foyer leads up to a drawing room. The walls are lined with tables laden with trophies of a storied career: photos, artwork, the stray musical instrument, awards, awards, and awards. I wish I could take pictures, but I don't have time. I am ushered upstairs to meet the king.

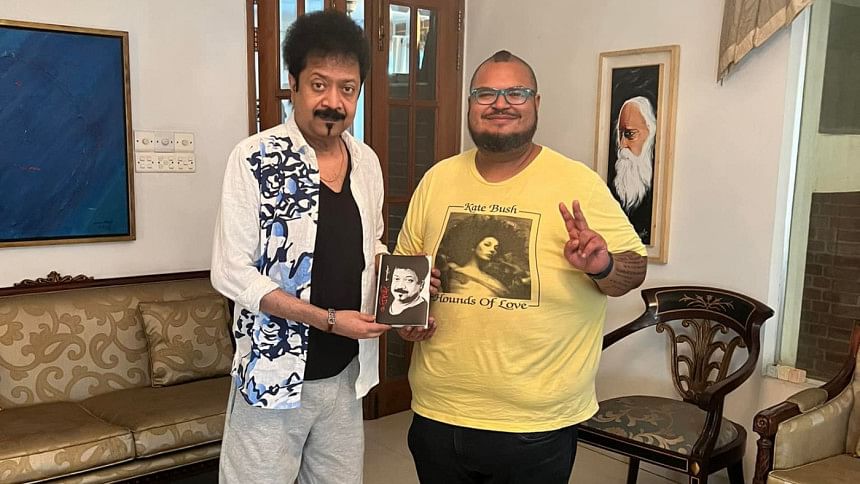

I'm here because my friend Chisti Bhai did me a favour—he arranged for me to meet one of my heroes. I'm getting second thoughts now. Sitting in a "boroloker drawing room" is always awkward. The sofa might cost more than your kidney, plus, I'm a big guy. I'm waiting to meet the man who defined pop stardom for my generation. And just as I settle into the spotless white leather, he enters like a hurricane.

Kumar Bishwajit looks like he could be anywhere between 30 and 45, although I know he's older than that. I met him at the start of my own musical career. He took me aside, complimented me, and told me to keep practicing. "Learn to play tablas," he told me, adding that "It's about playing music, not just hitting things." I did not know then, but found out later, that he did the same with every musician from my cohort.

When Bishwajit was barely an adult, he moved to Dhaka with a few hundred takas to his name. "It was the late 70s and we had a spirit of adventure. I told my parents I was giving up the financial stability of our family business to pursue a career in the arts. I took a train to Dhaka, put up in a hotel, and ran out of money by the end of my first week."

Bishwajit was not the only musician to make this journey. Chittagong, being Bangladesh's biggest port, was for many decades our introduction to international culture. Musicians from Chittagong have always been innovators, risk-takers, and the prime movers of the first great generation of Bangladeshi rock.

When Bishwajit talks about his early struggles, I don't see a middle-aged man reflecting on a long career. I see a young, hungry artist eager to make his mark—on Dhaka, on Bangladesh, on the whole world. He dances nimbly between topics: a young man's thirst for fame, playing concerts in every major world capital, his recently published biography "Ebong Bishwajit " by Joy Shahriar. Always, the conversation returns to his old friends, Naquib Khan, Khaled Hassan Milu, Ayub Bachchu, and the elusive Larry whose name we know but who has few extant recordings.

Bishwajit is ever enthusiastic, whether he's pushing tea and snacks on you, sharing the concept behind his next project (there is always a next project), or explaining the provenance of a 200-year-old percussion piece that he snagged from a tribal temple. His joie de vivre comes out in full, unrestrained force whenever he is talking about his old friends. Khaled Hassan Milu is long gone, Ayub Bachchu has left us too. But in his memory, it is like they still live every day. Bishwajit tells me stories about how they wrote songs in lazy winter afternoons, songs of love and loss, songs that became the defining touchstone for Bangladeshi pop culture.

Some legends are enigmatic. However, there is no mystery behind Bishwajit —he exists as a pure force of art, love, and the constant hunger to create something new. To millions of non-resident Bangladeshis (NRBs) worldwide, Bishwajit is the only Bangladeshi musician they will experience live. He is a tireless jetsetter, a global ambassador, who flies first-class to any city in the world with a Bangladeshi audience.

Computers and smartphones have now made it easier for solo performers to tour. However, this wasn't always the case.

"I had to go on stage with a skipping CD! I kept singing the chorus over and over again. Another time, my band couldn't make it and it was just me at the last minute," recounted Bishwajit.

I saw Bishwajit play in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 8, 2004. I remember the date because that was the day Dimebag Darrell was shot. Back then, like the sturdiest windmills, I was a heavy metal fan. But when Bishwajit sang "Tore Putuler Moto Kore", I screamed "Ami nei, nei, nei re!" with the rest of the audience. I also remember shouting "Sword blades!" when he sang "Tumi Roj Bikele", a song that was featured in a television commercial in the early 80s. And there was not a single person sitting when he brought the house down with "O Daktar".

"Funny story about that song," says Bishwajit, "I once broke my leg the morning of a concert. I asked them to put me in a wheelchair and I went on stage with my leg in a cast. The audience thought it was a gimmick. But I explained that even though I was injured, the show must go on."

Bishwajit co-founded Gaanchill Music in the mid-2000s to nurture artists and give them a fair revenue share. He helped develop it to become one of the biggest labels in Bangladesh, and then he returned to his music. I have been alive for as long as he has been releasing albums. To me, the groove of "Disco Piyashi" is as significant as "Shudhumatro Tomar Jonno". As a journeyman musician, a kingdom where he reigns as a benevolent poet-king, perhaps the most lovable quality Bishwajit possesses is his unrestrained love for all musicians. Whether it's Naquib Khan, Jalali Set, or a busker in Spain. Bishwajit approaches all of these musicians with an open mind and a welcoming heart.

I namedrop as many musicians as I can just to see if I can get him to criticise someone. No dice. When he speaks of Pritom Hasan and Protic Hasan, his late friend's musician sons, his voice swells with pride. He is hopeful for this generation of musicians, as he well should be—he helped create this.

Bishwajit is not one to talk about his success. To him, the past is where his friends are, the long days of pre-Internet, pre-cable Dhaka, when he could pick up the phone and ask Ayub Bachchu and Kazi Hablu to play on the song he just wrote. The past is where he keeps memories of his mother, for whom he installed an elevator in his house. The past is where his vast collection of vintage and antique musical instruments was created. The past is where he received hundreds of awards lying carelessly all over this mansion that he built, not with a familial inheritance but with money he earned with his creative force and golden voice. Bishwajit exists in the present and future—visiting his son Nibir in Canada, creating new music, driving his sports cars, traveling in the post-COVID world bringing the songs of Bangladesh to any pair of ears that will listen.

As I sit there, eating his food and cuddling his beloved dog Candy, I reflect on his body of work. Nobody, not even Kumar Bishwajit himself, will ever know the many ways his music has touched the lives of millions.

Without meaning to, I open to him. I talk about my own musical ambitions, about the craft of drums and percussion, about my best friend, my cats, my dog Moushumi. When I tell him about Hothat, a documentary I made with friends, he jumps in joy and claps me on the back.

He listens to my entire life story as if it's the most meaningful narrative he's ever heard. In his mind, Bishwajit is still a teenager making music with his friends, living out of a hotel with empty pockets, about to conquer the world with his irrepressible joy. May we all love as freely and create with such courage.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments