Beyond development paradox & unnayan without democracy

As Bangladesh seeks to recalibrate its path in the aftermath of recent upheavals, the time is ripe to revisit an oft-invoked but under-examined agenda: institutional reform. Institutions are crucial to understand, as they are foundational for governance, transformation, and economic development. It is tempting to dive straight into prescriptions—restructure this ministry, decentralise that department—but such surface-level enthusiasm risks masking deeper, structural blind spots unless we first confront a fundamental challenge: our burden of flawed narratives. Reform narratives orient us to focus on certain aspects of institutions while overlooking others—ultimately shaping which policy actions are prioritised.

In the 1990s, a popular intellectual shorthand coined by some economists described Bangladesh's experience as a "development paradox"—growth without governance. When governance was said to be absent, the empirical focus was largely on corruption—primarily measured through indicators like Transparency International's rankings, which listed Bangladesh among the most corrupt countries. The phrase caught on, reinforced by these international rankings of corruption and governance deficits. Yet this narrative glossed over key institutional breakthroughs during that same period, which was also marked by competitive politics. Private banking and private universities emerged in the early 1990s, marking major institutional expansion in the finance and education sectors. The period also saw the transformative spread of mobile telephony and the institutionalisation of social protection programmes such as the old-age allowance and stipends for primary and girls' education.

These were not anomalies; they were significant governance reforms that underpinned growth and social development. Corruption was certainly a reality in that period, but the narrative framing was flawed because it overlooked major governance reforms in banking, education, and telecommunications. To reduce the decade to a 'growth without governance' paradox was to obscure the very institutional drivers that enabled growth. This is why I want to emphasise that, when engaging with institutional reform, it is essential that the narrative is not built on a selective reading of the empirical record.

The misalignment between narrative and empirical reality was not unique to the 1990s. Fast forward to the period of the fallen regime from 2009 to 2024. We again witnessed the re-emergence of a similar paradoxical narrative. This time, the dominant discourse was 'unnayan without democracy'. While apologists for the autocratic regime promoted the idea that development did not need democracy and growth must be pursued at any cost, this too was a flawed narrative. Beneath the surface, competitiveness declined, the employment elasticity of growth sharply dropped, and inequalities reached alarming levels. Economic and political governance—particularly of the transformative kind—retreated.

The cost of flawed narratives is not merely semantic. They orient our gaze towards certain institutions while rendering others invisible. Consider two broad types of institutions: watchdog bodies and grooming institutions. Watchdogs are designed to monitor and enforce accountability—catching corruption, ensuring compliance. Grooming institutions, on the other hand, do not punish but instead focus on nurturing and building capacity, developing people, and strengthening systems. Unfortunately, due to dominant but flawed narratives, our reform efforts have historically leaned too heavily towards watchdog-type institutions. As a result, we tend to overinvest in bodies tasked with punishing deviation, while neglecting institutions designed to nurture competence and initiative. The Anti-Corruption Commission or consumer rights bodies may attract media attention, but where are the institutions that build the next generation of public health professionals or local administrators?

The second point I want to raise is about clarity of purpose. We often talk about restructuring institutions—how a bank should be managed, or how a ministry or an agency could be reorganised. But before institutional reform can be meaningfully undertaken, we must ask: what are the end goals we seek to achieve? What is it we want these institutional reforms to deliver? Otherwise, institutional reform risks being driven by narrow bureaucratic interests. For example, a ministry might push for changes that serve its internal concerns, rather than broader national priorities—better service delivery, greater equity, faster justice, enhanced preparedness, or stronger accountability.

What are the end goals of reforming economic governance? Growth, yes—but what kind? Bangladesh can no longer rely on the old formula of cheap labour. If we do not transition towards a growth model rooted in productivity, skills, and domestic innovation, we risk stagnation. Do we want an export-driven strategy only, or one that equally values the domestic economy and its potential to drive inclusive growth? What are the new growth drivers beyond RMG and remittance that can take Bangladesh further in its economic journey? Are we listening to entrepreneurs on the ground to identify and nurture these potential new drivers? Should we not hold a summit—like the recent one on foreign investment—to support and encourage local investors, many of whom may already have considerable resources to reinvest in the country? How can the focus on employment generation be placed at the heart of the growth strategy? These are the priorities that the reform narrative must embrace as its key end goals.

Economic justice too has emerged as a defining aspiration. And it is not just about poverty alleviation or redistribution. It is about ensuring that local governments have the autonomy to act, that informal workers find pathways to formal protection, and that domestic investors are not crowded out by headline-grabbing FDI summits. It is about ensuring that the benefits of reform are not monopolised by a few but reach the many.

Reimagining the economic role of the state is also critical to getting the reform narrative right. Today, as the stability of the global trading system comes under strain, economic nationalism has once again emerged as a significant idea. However, neither market fundamentalism nor the command economy concept of an earlier era is particularly useful here—nor is a bureaucratic dominance that is red tape–friendly and hoirani-prone. Institutional reform needs to strengthen that part of the economic role of the state that catalyses innovation and long-term resilience.

Looking at Bangladesh—and indeed, South Asia more broadly—there is a particular character to the way economic transformation happens, quite different from East Asia. Much of the transformation in Bangladesh has been initiative-driven rather than policy-led. In many cases, progress occurred not because there was a clear policy, but because someone took initiative—within or outside government.

For example, farmers began experimenting with solar irrigation techniques on their own, and over time, this reshaped the agricultural landscape. So, when we talk about institutional reform, we must ensure that new regulatory burdens do not close down these spaces for individual or collective initiative. Over-regulation can end up stifling this vital source of innovation.

Yet even where reform initiatives have been launched, many have ended in dead ends. We have created institutions without staffing them properly. We have built infrastructure without equipping it with the necessary personnel or decision-making power. Consider BARD in Cumilla, once envisioned as a global centre of excellence, now faded from prominence—not for lack of vision, but because human resources and autonomy never caught up with infrastructure.

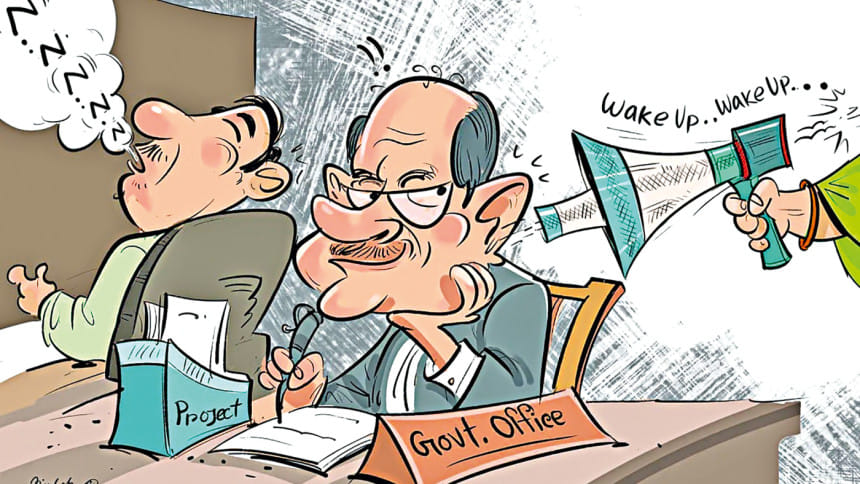

Not filling sanctioned posts at operational levels year after year is an institutional disease across the gamut of the public sector. Service delivery institutions—hospitals and ports, to name just a few—lack critical financial and administrative autonomy. Specialised institutions are often headed by generalist administrators, their leadership determined less by expertise and more by bureaucratic convenience. Reform agendas become vehicles for career placements rather than systemic transformation. The result is institutional mimicry—reform in form, not substance.

The reform narratives have also been overly supply-driven. Demand-side inputs, especially from SMEs, youth, women, and local actors, remain weak or co-opted. During a recent dialogue with small business owners, one entrepreneur lamented: "We are asked for feedback but never see it reflected in the final policy." FBCCI and other chambers were meant to be demand-side vehicles—but are they truly voicing the policy and reform needs of the community? Similarly, SMEs lack organisational channels to push for reforms that would benefit them. Other countries, like Turkey, have successfully set up such vehicles, allowing both large and small businesses to shape meaningful reforms.

Some imperatives are now clear. First, we need a personnel policy that prizes merit and nurtures professional specialisation. Second, we must empower local institutions—not simply decentralise for form's sake. Third, we need a "redundancy audit" of outdated regulations. One such regulation is the requirement for police verification for jobs—a colonial relic that served little purpose other than delay and rent-seeking. It took years to roll back something that had long outlived its usefulness.

Think of the proverbial machhimara kerani—the office clerk who, having once killed a fly with a file, now repeats the ritual endlessly because it has become 'procedure'. Institutional reform must also address a cancer institutionalised by the autocratic regime: the mainstreaming of rampant conflicts of interest in economic governance.

Finally, the reform initiative must shift the focus from process to outcomes. Too often, institutional success is measured by whether a circular has been issued, not whether a problem has been solved. How results are meaningfully achieved must become the central concern of reform thinking. Such a mindset shift is long overdue.

Institutional reform, in its true sense, must go beyond merely creating new agencies or laws. At a deeper level, we also need to address the issue of policy sovereignty—which is not just about political independence but also about ensuring that the policies and reforms we adopt are genuinely suited to our needs and not overly influenced by external experts or agencies. To do that, we must first unburden ourselves of flawed narratives and rediscover the empirical truths and aspirations that truly define our national journey.

This speech was delivered by Dr Hossain Zillur Rahman, Chairman, Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC), at the 6th Bangladesh Economics Summit 2025, organised by the Economics Study Centre, University of Dhaka. The Daily Star team and Namira Shameem of PPRC assisted with the transcription of the recorded speech.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments