Ratites

On a grey morning three years ago in northern Queensland, Australia, I boarded a microbus with several other birders. After exiting the highway we drove a long, winding road through the rainforest. It ended at a two-story country house. This was Cassowary House, a dedicated birdwatchers' lodge for observing rare birds such as the Cassowary and Victoria's Riflebird.

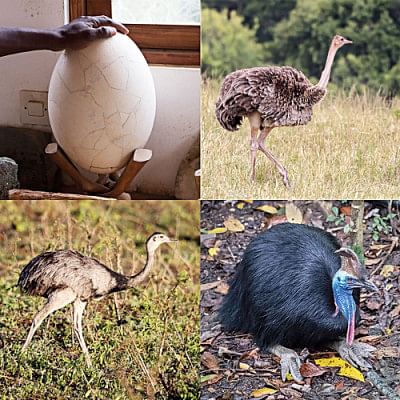

We were led to a long balcony on the second floor. The dense, lush forest lay in front of us. As we watched, various birds flew in to eat at bird feeders. Then something on the ground caught our eye. A plump black bird with a blue head and a red wattles wandered in and out of the forest. It was round and stocky, about five feet tall and weighing well over a hundred pounds, with a large growth, called a casque, on its head. Its body was covered with long black hair but no feathers. Its feet had three plump toes; the inner toe had a long, sharp claw.

The unusual bird is called the Cassowary. It can run at thirty miles per hour on its long legs, but it cannot fly. It belongs to a bird group known as ratites - large, terrestrial birds found in many parts of the globe. Having weak flight and wing muscles, ratites are flightless. Their breastbones are flat and lack a keel where flight muscles of normal birds attach to. Their feathers are unsuitable for flying.

The largest living ratite is the Ostrich which lives in open plains of Africa. It can reach nine feet in height and can exceed three hundred pounds. Despite its bulk it can run at thirty five miles per hour. The Ostrich is also farmed for feathers and meat.

Found in the grasslands of South America, the Rhea is another member of the ratite group. At less than six feet tall and weighing up to eighty eight pounds, it is smaller than the Ostrich. I have seen them both from afar; they look strikingly similar as they wander through open fields and grasslands.

The Emu of Australia is another large ratite at six feet and one hundred pounds. The smallest ratite is the Kiwi of New Zealand which is about a foot tall.

Several ratites have become extinct. Most remarkable was the Elephant Bird of Madagascar, the largest bird ever. It stood nine feet tall, weighed over a ton, and was alive until about a thousand years ago. In a museum in southern Madagascar I saw its reconstructed egg, over two feet tall.

Another extinct ratite is the Moa of New Zealand. It reached twelve feet and weighed five hundred pounds. It became extinct during the 1400s, a century or two after humans landed in New Zealand. With it went the large Haast's Eagle – twice the size of a Harpy Eagle – whose primary diet was the Moa.

How did these flightless birds come to be? Scientists once thought that ratites had descended from a common ancestor in the supercontinent Gondwana. However, there is now evidence to suggest that different species evolved into flightless birds independent of one another. The story of these similar birds is indeed mysterious.

www.facebook.com/ikabirphotographs or follow "ihtishamkabir" on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments