Change vs Tradition

Change is Good

RAYAAN IBTESHAM CHOWDHURY

Cultures have never been static. In fact if there is any one law that defines how traditions and customs thrive, it is change. But at the same time our culture is what makes us who we are. So it's only natural for us to be a bit taken aback when we wake up one morning to realise that the methods with which we practised things are changing. But despite our love for our traditions and our customs, let's not forget that change and evolution will always remain the driving force behind any society and culture is only a reflection of the lives of people within that society.

While there are some minor disputes, it is generally known that the Bangla Year or Bongabdo system was started by the Mughal Emperor Akbar, combining the Muslim Hijri and the Hindu Solar Years. But whether Emperor Akbar meant for it or not, the new system soon became a very key element of Bengal and everything associated with Bengal. Things like 'panta ilish' and the famous 'red and white' theme would attach themselves to the festival over time.

It is hard to pinpoint a common source of Bangaliana. Home to two very important sea ports, the Ganges delta has seen numerous cultures come and intertwine over the ages, and bits and pieces of every culture have stayed back. From Burma's lungi to China's tea, from the sub-continent's Hinduism to Islam from Arabia, the whole idea of Bangaliana has always been an eclectic one. Which brings me to my main point, how the traditions of Pahela Baishakh, the crowning jewel of Bengali Culture, will never stand still. For all it embodies, the festival will always have to evolve.

What started as an attempt by the Mughal government to administrate more efficiently, grew over time. Initially it was only restricted to the richer merchants, who opened new account books or halkhata on those dates. But the celebration did not remain limited to the 1 percent, with the festival soon reaching far and wide across the green horizons of the region. The mostly agriculture-dependant population couldn't throw grand parties or anything of that sort. They celebrated in whatever way they could, but something was very unique. Unlike religious festivals, this was one day where Muslims and Hindus, namely everyone, would join under the common banner of “Bengali” and usher in the New Year.

Its core ideal would reach its highest peak when Chhayanaut initiated the grand Pahela Baishakh celebration in the 1960s. The event, organised at Ramna Botomul, would bring back the idea of Pahela Baishakh as an almost essential idea in the lives of all who claimed to be Bengali.

Over time, the way in which people observe the festival has changed and it continues to do so. At all times it has remained a key reflection of what it means to be Bengali. When we struggled to establish our identity, the festival burned bright as a symbol of all the things we stand for -- co-existence, the love for colours, music and art. As long as these key ideas remain intact, just how people choose to celebrate the event will remain a largely superficial facet.

Special thanks to Shamima Akther Chowdhury, M.C. College, Sylhet.

***

Traditions should be Upheld

SHOUMIK MUHAMMED MUSHFIQUE

Love for festivity and celebration is a notable trait among Bengalis, and on no other day is this trait generally more manifest than Pahela Baishakh. It is the first day of the Bengali New Year and is greeted with a vast array of colours which adorn cities, streets, clothes and the faces of people. Pahela Baishakh is a festival that knows no ethnic boundaries or religion. It celebrates the cultural diversity and joyous camaraderie of the people of Bengal. Pahela Baishakh has always been about the rural roots of Bengal, and the humble beginnings of our culture. But despite the nationwide observation of this festival a lot is changing about how people, particularly urbanites, celebrate it. With time, perceptions have changed, and fewer people recognise the significance of this day.

Pahela Baishakh used to see people waking up very early, usually at dawn to see the sunrise. Of all the people I asked, only one person had an idea about this custom.

“Suppose you go to a party, have fun there,” says Lubzana, a Pahela Baishakh enthusiast, regarding viewing the sunrise on the day, “You have a great time but you don't greet your host. That's us ignoring this custom.”

“Watching the sunrise is how you greet the New Year, a new hope and a bundle of new opportunities,” she adds.

These days more and more people prefer staying indoors on Pahela Baishakh. Some go out with friends and spend time at university campuses where Baishakhi fairs are set up. During the day, there are numerous concerts by 'renowned' bands, musicians and DJs across the city with people flocking to those rather than the traditional folk music performances and artistic displays. Rather than helping themselves to a traditional course of panta and fried hilsa, a lot of people wait in lines at fast food joints in Banani or Gulshan. Many flood the lobby of The Westin. The only thing these folks have in common with people celebrating Pahela Baishakh the way it should be celebrated, are wearing bright panjabis and saris.

Handicrafts were ubiquitous on Pahela Baishakh but are now becoming increasingly rare. “Back in the day I used to go to the fair and bring back lots of handmade toys. I barely see those kinds of toys anymore, it's mostly Doraemon stickers these days,” says Lubzana.

It's not that people celebrate Pahela Baishakh improperly everywhere, but an alarming number of people have less regard for the significance of this day than they should. Very few of the people I consulted knew that in an attempt to suppress Bengali culture, the then Pakistani Government had banned poems and songs written by Rabindranath Tagore in the 1960s. Protesting this move, Chhayanat started their Pahela Baishakh celebrations at Ramna Park with Tagore's songs welcoming the New Year. The day continued to be celebrated in East Pakistan as a symbol of Bengali culture.

Pahela Baishakh is more than just another excuse to party in panjabis and fewer people realise that. It is an event that bridges all gaps -- religion, ethnicity and even class, so that there is one day when people from all walks of life can celebrate our unique, diverse culture.

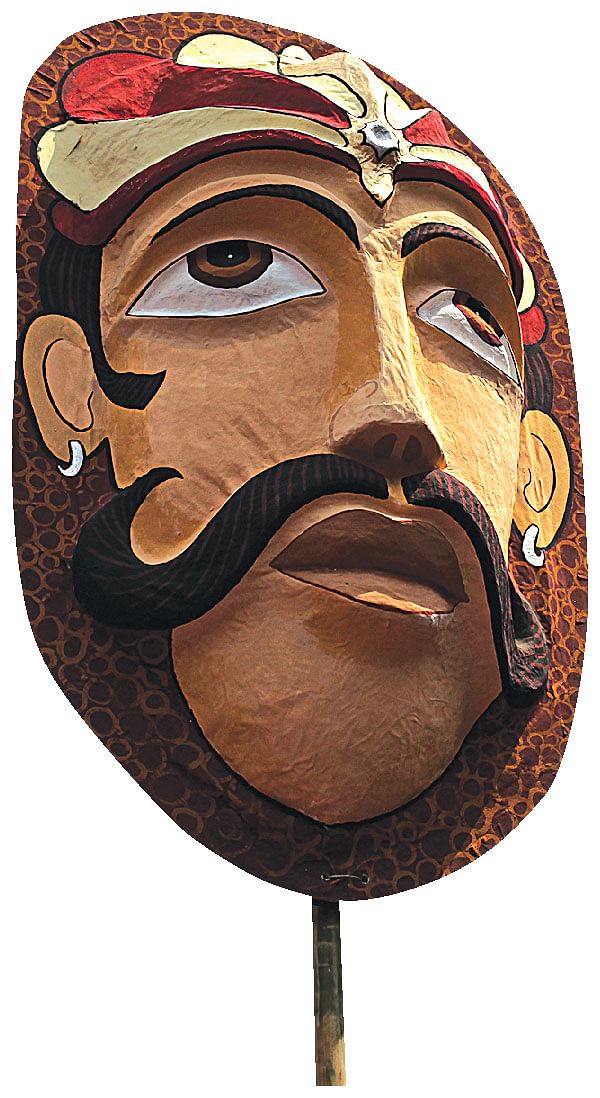

Photo: Ridwan Adid Rupon

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments