The sacred architecture of story

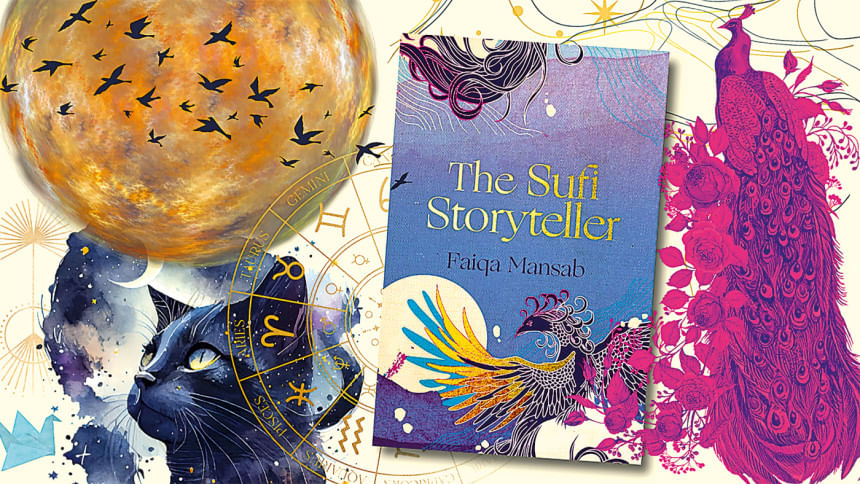

Faiqa Mansab's second novel, The Sufi Storyteller, is a quiet triumph—both elegiac and urgent, intimate and expansive. It arrives as a natural evolution from her acclaimed debut, This House of Clay and Water (Penguin Random House India, 2017), and yet it stands apart, not merely in ambition but in execution. Where the former was steeped in the politics of desire and gender within Lahore's elite and unseen spaces, The Sufi Storyteller ventures across continents and metaphysical thresholds to bring forth something more elusive: the sacred, storied terrain of the inner world.

The novel traces the entwined journeys of Layla, a scholar of women's histories in a small American liberal arts college, and Mira, a Sufi storyteller bearing the weight of a terrible past. A woman's murder becomes the axis upon which the narrative turns but this is no ordinary mystery. The crime is a disturbance, a crack in the carefully composed surfaces of both women's lives, through which memory, story, and sorrow begin to leak and, eventually, flood.

Mansab's feminism here is not polemical. It is textured and spiritually aware. In Layla and Mira, she gives us women shaped by grief, marked by exile, both geographic and emotional and yet capable of immense compassion, complexity, and transformation. These are not heroines molded for clarity; they are rendered in chiaroscuro, in shadows and contradiction.

At the heart of the novel is a profound meditation on the act of storytelling itself. Mira, whose voice carries the cadences of oral tradition, represents the instinctive, intuitive knowledge passed down through generations of women, mystics, and keepers of the unsaid. Layla, in contrast, approaches stories through the lens of research and archival authority. It is this tension between text and telling, history and memory, intellect, and emotion that Mansab renders with delicate nuance.

Her prose is lyrical, spacious, and deliberate. It evokes the tempo of Sufi narrative. There is repetition that deepens rather than dilutes, silences that echo, and imagery that unfolds like a dervish's dance: circular, layered, and revelatory. The "realm of story" that Layla and Mira enter is not merely symbolic; it is crafted with mythic resonance, a liminal space where past and present, dream and trauma, are interlaced like threads in a Sufi's robe.

In many ways, the novel resists Western narrative conventions. Its emotional crescendos do not coincide with plot twists; rather, they emerge from moments of recognition, from fragments of stories buried within stories. The murder mystery, though present, serves more as a structural whisper than a genre anchor. What unfolds instead is a deeply feminist excavation of the silences within women's lives, the silences they inherit, absorb, and sometimes choose to carry.

Mansab's feminism here is not polemical. It is textured and spiritually aware. In Layla and Mira, she gives us women shaped by grief, marked by exile, both geographic and emotional and yet capable of immense compassion, complexity, and transformation. These are not heroines molded for clarity; they are rendered in chiaroscuro, in shadows and contradiction.

There is also something remarkably generous in the novel's embrace of Sufi thought, not merely as a backdrop but as an epistemology, a way of knowing and being. The Sufi parables that flow through the text serve as both metaphor and method. They are not neatly decipherable; rather, they are offerings. This refusal to over-explain, to smooth the reader's path, is one of the book's greatest strengths. It invites surrender rather than control.

Compared to This House of Clay and Water, this novel is more ambitious in scope but also more refined in its craft. The voice is quieter, more assured. The characters are less constrained by place and more in dialogue with timeless questions of self, truth, and forgiveness. Yet the thematic threads remain: the body and its discontents, the power of voice, the haunting presence of the unsaid.

The world Mansab conjures is lush with metaphor, but it is also grounded in the visceral. A woman's death, a note from a killer, a journey into war-ravaged mountains, these are not abstractions but anchors, gestures toward how violence inscribes itself upon language, memory, and gendered experience.

In The Sufi Storyteller, Faiqa Mansab offers a novel that is not only about story but made of story, its fragments, its echoes, its capacity to both wound and mend. It is a deeply literary work, one that asks for patience, reflection, and above all, listening. For in this world, it is not the loudest voice that reveals the truth, but the one that has endured the longest silence.

Namrata is a published author who enjoys writing stories and think-pieces on travel, relationships, and gender. She is a UEA alumnus and has studied travel writing at the University of Sydney.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments