‘Human translation will continue, despite machines’: An interview with V. Ramaswamy

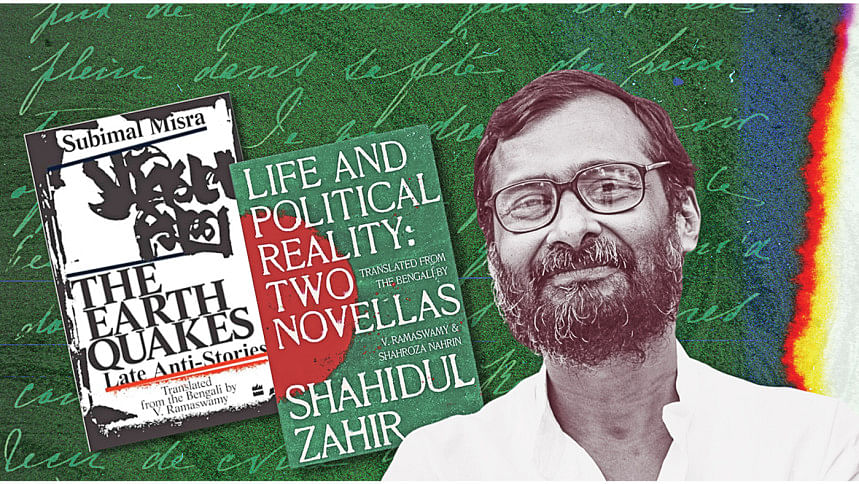

V. Ramaswamy is a translator and writer based in Kolkata, India. I had first heard of him in early 2022, when a new book of translations of Shahidul Zahir was being written about in newspapers here in Bangladesh and in India. Yet it would be his work on Shahaduz Zaman where I first experienced his craft. A translator of writers such as Subimal Misra, Manoranjan Byapari, and Adhir Biswas, I found his translations to be effortless forays into the bleak world of these writers.

Speaking with Ramaswamy on behalf of The Daily Star about his life as a translator, he also shared insights on his upcoming projects and, among other things, thoughts on whether AI could ever be a serious translator.

Tell us how your journey as a translator began.

It began almost by accident in 2005. During a casual encounter with my friend Dr Mrinal Bose, I asked him if there was one contemporary Bangla writer who he thought was worth reading; he thought for a moment, and said, "Yes. His name is Subimal Misra." And thus, with Dr Mrinal's prodding and pushing, I began translating Subimal Misra's short fiction. But after that initial start, I persisted with translating Misra because his writing resonated with my own background as a grassroots and community organiser and activist, working with the labouring poor of my city for two decades. I was selected for the Sangam House residency in 2011—and it was the Sangam House residency that made me a translator. After completing three volumes of Misra, I saw myself as a translator of voices from the margins. That was when I learnt about the autodidact writer Manoranjan Byapari, and received the novel Chandal Jibon from him. A three-month fellowship in Wales in 2016 enabled me to work on this. For me, that was an apprenticeship in working on a long novel.

You are currently translating Prodoshe Prakrito Jon, what drew you toward the works of Shawkat Ali?

It was my translation assistant, Srishti Dutta Chowdhury, who told me in 2020 about Shawkat Ali's novels, Prodoshe Prakrito Jon (The United Press Limited, 1984) and Narai (Bidyaprokash, 2012). She wanted to translate these, and asked me if I would join her. But it was the way she described these two novels that had a mantric effect on me. As it happened, Srishti was unable to devote time to this; also, following the experience of a collaborative translation of Shahidul Zahir with Shahroza Nahrin from Bangladesh, I thought I ought to induct a Bangladeshi co-translator for Shawkat Ali as well.

I had the consent from the late Shawkat Ali's family in a matter of hours. That was only because of my network and circle of friends in Bangladesh. Similarly, my eventual co-translator on the Shawkat Ali project, Mohiuddin Jahangir, was introduced to me by Asif Showkat, the author's son, now a good friend. Mohiuddin's PhD thesis was on Shawkat Ali. We completed the novel, Narai, titled We Must Fight! in English.

It began almost by accident in 2005. During a casual encounter with my friend Dr Mrinal Bose, I asked him if there was one contemporary Bangla writer who he thought was worth reading; he thought for a moment, and said, "Yes. His name is Subimal Misra."

You have been part of multiple translation projects as a co-translator. How different is the process of translating in collaboration?

I had no plan as such to collaborate; it was just a sudden thought, and so I invited Shahroza to join me as a co-translator of the novella, "Life and Political Reality", by Shahidul Zahir. I had become acquainted with Shahroza Nahrin via Facebook. I arrived in Dhaka in early 2020 and sat with her for a few days; she read out, and I translated.

This first experience was a happy one, and it convinced me that when it comes to important texts, two is definitely better than one. Two people can share the ownership, responsibility, and labour of translation.

I would like to think that this was also a good mentorship experience for my co-translator. Bangla needs a Mukti Bahini of translators, and so this collaboration-mentorship process can also be a means towards building more translators.

What do you think of machine translations in the sphere of literature? Should it ever be taken seriously?

I guess machines will gradually get better and better, but until then we, humans, will carry on translating. Like literature, translation is a human act, a human choice, and the translator brings his humanity to play in his or her work. And so what we get is a creative, human, artistic work. AI can write a short story or a novel. Will it ever be as good as anything humans have ever written? I don't know. But I don't think I would be interested in reading any literary work produced by AI. AI can generate images in a fraction of a second. But we will still look with awe at the works of the great masters. Will people stop expressing themselves in drawing and painting? Will people stop writing? So human translation will also continue, despite machines.

How do you deal with cultural nuances when translating from Bangla to English?

I guess one has to be embedded in the culture in order to perceive and sense the nuances. The translator must then bring this to the fore creatively. For instance, if someone addresses an older person as "tui" rather than "apni", that conveys something about sociology—about classism being ingrained in the culture. A particular word or term may be very significant, from the perspective of history, or politics, like Ponchasher Monontor, or Mir Jafar, or Dandakaranya. The translator has to be ever alert. Readers of a translated work thus also learn about the history, politics, culture, etc. of a people.

There is something else I'd like to share in this context. When one translates, say, proverbs, there would be equivalent expressions in English. Like, "as you sow, so you reap". But there is an expression in Bangla, "katth khele angra hagbe" (if you eat wood, you'll excrete charcoal). Rather than translate that into a tame expression like "as you sow, so you reap", I would like to give the reader a peep into the psyche of the speakers of Bangla, the pungency of the speech, etc. So I would translate the original expression itself.

This is an excerpt from the interview. Read the full article on The Daily Star and Star Books and Literature's websites.

Shahriar Shaams is a journalist at The Daily Star. Instagram: @shahriar.shaams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments