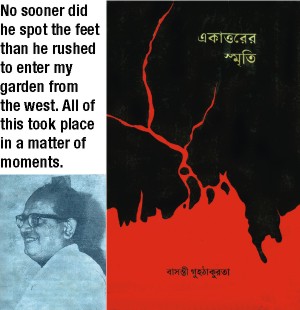

Murder in the Teachers' Quarters

(Excerpt from Ekatorrer Smriti by Basanti Guhathakurta. Translated by Meghna Guhathakurata

I don't know how long I had been asleep, but around twelve-thirty - one o'clock we awoke to the sound of gunfire. 'Does this mean that the war has started?' I asked my husband(1). He replied noncommittally: 'Oh, that's nothing sounds like the boys practicing.'(2) Gradually the sounds drew near, very near. I then brought Dola(3)) into our bedroom, onto my bed. I switched off the light in her room, leaving only the green bed light on. A little later there were flashes of light, accompanied by terrifying sounds. And what sounds! Our house started to shake as if in an earthquake, with the windowpanes rattling. Calling out to Swarna(4) to join us, I stripped off the bedsheet and laid it under the bed, where the three of us huddled together with our heads down. Swarna did not heed my call. 'If I have to die, I'll die in my own room,' she said. We called out to Gopal(5) too, but nobody came. Dola's father told her, 'Listen Dola, the war has begun! During wartime this is the way one lives in trenches. Eating, sleeping, defecating...everything done in the same place.' What we were hearing was no ordinary gunfire. It sounded very heavy. The skies over Jagannath Hall lit up from time to time and the hall itself seemed to be rent apart by the sound of heavy machine-gun fire. What was missing were human sounds. How could there be any, when every other sound, of human beings, of birds, was being drowned out by the sounds of guns. From time to time one could hear cows lowing. They were almost certainly the cows owned by the gardeners of Jagannath Hall, calling out in helpless terror. And the crows - the rulers of our neighborhood's trees - where on earth had they flown to? I fidgeted underneath the bed, wanting to get up and look outside, but both father and daughter held me back. As soon as the gunfire subsided a bit, on hearing a hissing snake-like sound I leapt up. This time they could not restrain me. In an instant I was at the window that faced the outer gate, drawing aside the curtains just enough for me to peep out. My husband, pulling me back by my hands, said: 'Keep your head down, you'll get shot!' I saw a convoy of army jeeps advancing slowly from the direction of Rokeya Hall and coming to a stop in front of the barricade at the crossroad. An officer got down and with a single pull of his hand tore off the chain around our gate. Immediately afterwards columns of soldiers swarmed in and went up to all the floors of Building Number 34. And started to violently kick at all four doors of the two flats on each floor. What a terrifying sound! The ears were deafened by the sounds of bullets and gunfire! In the meantime an officer smashed the window of my daughter's bedroom, ripped open the netting with his bayonet, drew aside the curtain and looked inside. Both the green bed light as well as the light in the south corner of the garden were on - no room in the house was therefore completely dark. Thus, though our heads were under the bed, our feet were showing. No sooner did he spot the feet than he rushed to enter my garden from the west. All of this took place in a matter of moments. I took my husband's punjabi from the clothes rack and handed it to him: 'They have come to arrest you, get ready.' Both of understood that they had come to get him. He said: 'Take Dola into the drawing room and lay her down.' Gopal, from his room above the garage, was signaling to us not to open the door. But I had no choice, since Dola, clutching a pillow to her chest, had gone to the drawing room only to find that its door was being hammered on too. She ran to the verandah. In the meantime, the officer again with a single pull wrenched open the kitchen door, roughly shoved Swarna out into the garden and entered the verandah. I stepped forward. He asked in Urdu: 'Is the professor here?' No use lying to him, I thought. 'Yes,' I replied. He said, 'I have to take him away.' I caught hold of the officer's hand and asked, 'Bhai, where are you going to take him?' He avoided looking at me and instead with his eyes downcast on the floor, stepped forward along the verandah, slowly spinning out the words: 'We'll just take him.' I followed him, walking behind as if it was his house. I said: 'Now that you are inside the house, why are they still trying to break down the front doors?' He rang out an order, shouting out a name: 'I am here, Yaqub! Stop breaking the door!' Immediately the kicking and banging stopped. Moving towards my bedroom, he asked: 'Are there any young people here?' I replied,'I have only one daughter.' 'All right, the girl has nothing to fear.' I entered the bedroom to see that Jyotirmoy standing with the punjabi still in his hand. The officer caught hold of his left hand. I pulled the punjabi over Jyotirmoy's head and said: 'They have come to arrest you.' The officer asked him, 'Are you the professor?' My husband replied evenly: 'Yes.' 'We have to take you,' the officer said in Urdu. Again, in a measured tone Jyotirmoy asked: 'Why?' But without any further ado, the officer grabbed hold of Jyotirmoy's hand and pulled him straight through the verandah and out into the back garden. I grabbed a pair of my husband's sandals and ran after them but they were gone by then. When I returned to the house I saw, through the netting on the front door, Mrs. Maniruzzaman standing on the stairs above me, while in the landing below Dr. Maniruzzaman(6), his son, his nephew and another gentleman tussling desperately with the soldiers, who were dragging them away. Mrs Maniruzzaman exclaimed to me: 'Didi, do you see how they are pulling at our menfolk!' This was my first meeting with her. They had just moved in into the flat on the second floor on March 5th. I said: 'Give them your husband, otherwise they might kill him. Just now they’ve taken my husband to the cantonment.' Right then, two shots were fired outside. My daughter held her hands to her ears. The officer came back to our flat and began to break the lock on the door to the dining room. It was a Godrej lock, which I opened for him. Then he methodically searched the three bathrooms, one after the other. Entering Dola's bathroom, he said: 'Where is Mujibur Rahman?' Dola replied: 'We don't know him.' In response he barked at her so harshly that my daughter instantly clutched at me. Then they went out again through the garden. When I was in our verandah with my daughter, about eight shots rang out in our stair landing. I rushed to the door netting in time to see the soldiers marching away. Dr. Maniruzzaman was lying next to the front door of my drawing room while the other three were lying in a heap near the door of 34-B, groaning. Blood was flowing everywhere. Mrs. Maniruzzaman cried out: 'Look at what happened, didi, you said they wouldn't kill, but see what they have done!' What could I possibly say to her then? They were all crying for water. Dr. Maniruzzaman was moaning. Mrs. Zaman gave them water. By this time the barricade at the crossroad had been cleared and the military convoy consisting of eleven trucks and jeeps sped towards the Central Shahid Minar. How much brutality had they inflicted within such a short time! After the convoy left, Swarna and Gopal came out from their rooms and asked: 'Didimoni, where is dadababu?' I answered: 'They arrested him and took him away. Here, you look after Dola.' I felt certain that he had been in the convoy's first vehicle. When I returned to the netted doorway, Mrs Maniruzzaman pleaded with me: 'Didi, please help me take my husband to the hospital!' I replied: 'But can't you hear the vans' loudspeakers saying that there is a curfew on.' I rushed back to my daughter. Then Mrs. Maniruzzaman called out: 'Didi! They've shot your husband and left him outside! I just gave him a drink of water. He seems to be all right. He's talking. If you take him to the hospital he might live.' Dola exclaimed: 'Ma, I heard Father call out my name.' Mother, daughter, and Swarna immediately ran down the garden path. Near the front gate, we saw Jyotirmoy lying on his back on the grass by the side of the building. On seeing us he said in a grave voice: 'Didn't you hear me calling you?' Dola answered that she had. 'They have shot me in the neck on the right side,' he said. 'I am now paralysed from the waist downwards. You'll have to carry me inside.' Till now I had been letting out cries of despair. Upon hearing his words my head reeled. He had once told me, 'If ever I am paralysed, be sure to shoot me.' My heart was in my mouth; Jyotirmoy's father had also suffered paralysis and had died just before his Matriculation exam. It was a most painful memory for him. I thought of it now. Oh God, now the very opposite had happened: He had been shot first and paralysed second. But listening to him one would think that he had merely had a regular accident. The three of us tried to lift him off the ground but couldn't. Swarna went and got Gopal. The four of us with a lot of effort somehow managed to bring him to the bottom of the staircase leading to our front door. There was blood everywhere. My feet kept slipping on Dr. Maniruzaman's fresh warm blood. What can I say, the scene was indescribable. But it was not a time for reflection. Neither of our doors could be pried open properly. With difficulty, we laid his bloodied body on the roped cot near the door to the verandah. I told Gopal to go and hide by the pond. He went out at a run through the gap between our kitchen and the garage to the pond behind. Then the three of us pushed the cot the entire length of our verandah to our bedroom door. Army vehicles were patrolling the area constantly, and the person lying on the cot could easily be seen by those inside the vehicles. So again, with much effort, catching hold of the mattress, we pulled it down to the floor, where the army men had originally seen our feet sticking out from under the bed. Jyotirmoy asked, 'Swarna, could I have a cup of tea?' The tea had already been prepared, had been kept in a flask. Swarna poured it out. Sipping the tea he told us, 'They made me face the hall (to the west) and asked my name and religion. As soon as I told them my name and religion, they shot me in the neck and I fell down paralysed.' He then asked Swarna to fold his legs and hold his knees together. But as soon as Swarna attempted to do so, both knees fell limply to each side. The nerves had been severed. He then instructed her, 'Light a hurricane lamp and apply heat to my legs.' Swarna did so accordingly. Dola started to cry and said, 'Ma, please call my principal at Holy Cross school, Sister Marian and ask her to send an ambulance. We'll take him to Holy Family.' But, oh heavens, as soon as the army had taken him away I had rushed to the phone to try and reach Birbal, the guard at my school. But the phone line had been cut. I now tried to staunch his bleeding with cotton wool. My husband said, 'Basanti, climb over the wall to the Nurses' Quarters and get two nurses.' 'How is that possible! The army is patrolling the streets. There's a curfew.' And besides, what strength did I have left in me? If something befell me what would happen to Dola? I felt helpless. I did not even have the courage to run across the road! While we were preoccupied inside, out on the stairs Mrs. Maniruzaman, her daughter and her sister were frantically tending to their four family members. Within ten minutes Dr. Zaman died, before everyone else. The other two kept groaning till they, too, fell silent... Postscript: Dr. Jyotirmoy Guhathakurata died on the morning of the 30th at Dhaka Medical College Hospital. NOTES

(1) Dr. Jyotirmoy Guhathakurata was Professor of English at Dhaka University and provost of Jagannath Hall at the time of his murder.

(2) He meant the students then practicing civil disobedience drills.

(3) Nickname of Dr. Guhathakurata's daughter Meghna Guhathakurata, the translator of this article. She teaches international politics at Dhaka University.

(4) Swarna, a domestic help who had been with the family for 20 years.

(5) Gopal was the driver.

(6) Dr. Maniruzzaman was Head of Statistics, Dhaka University.

|

|