Book Review

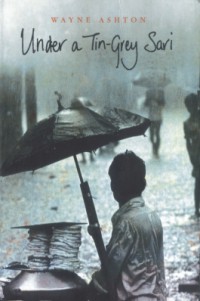

A tale twice told: Wayne Ashton's Under a Tin-Grey Sari

Syed Manzoorul Islam

The title of Wayne Ashton's (an Australian with 'British and Pakistani family origins' according to the author bio) book is suggestive, inviting comparisons with the salacious song 'Choli ke niche keya hai,' but alas! the sari in question is the heavy, grey monsoon sky that hangs over Chittagong before emptying itself on the denizens below. The denizens are a mix of the elite and the subaltern; but the elite seem strangely disempowered, while the subaltern surrealistically empowered--to the extent that they guzzle foreign beer like water. The novel's two main characters, Khalid and Zeythi, are the cook and ayah respectively of a rich household whose men are rarely seen and heard. Khalid and Zeythi, between themselves, have pretty much the whole run of the house. While Khalid controls the kitchen where sometimes he chops vegetables between sips of beer, Zeythi controls Khalid's imagination and that of the eight-year-old Minisahib, the precocious grandchild of the master of the house. Yet Khalid is only 19 and Zeythi 16. Ashton must have a world of sympathy for the (very) young and the restless--for he allows even the Minisahib to have regular sexual gratification from his many encounters with Zeythi. She for her part arrives at the household with more than a job seeker's intent--she also wants to pry into the sex lives of the employers. Once she creeps up to a window 'to watch a sahib and memsahib making love. To confirm the rumour that these sahib types moaned differently' (15). In case one wonders if it is the same Chittagong where at least a dozen pairs of eyes should be registering every move a woman and a man--or a boy--make, even in a remote part of a household, Ashton nods reassuringly. It is Chittagong indeed, but circa 1967, a colonial time in Ashton's reckoning, when hand-pulled punkahs were as common as people with names like Mookerjee or Aranthi, and when rich households drank enormous amounts of lychee juice while an Englishman controlled the elite club of Chittagong with the unquestionable authority of a chota lat. And yes, the house--'ten-ten Zakir Hussein Road'--had a forest edging its backyard, so that Zeythi's frolics with the little master were screened by dense vegetation. The club's swimming pool, at night, was a second site of Zeythi's frolics, yet not even the night guard notices anything amiss. Lucky girl!But to be fair to Ashton: Under a Tin-Grey Sari is not a historical or realistic novel which has to pass the test of verisimilitude. If anything, the novel is a postmodern tour de force in which no formal schema holds sway, where time appears as fluid as the thought processes of the protagonists and the margins between reality and unreality, action and contemplation, disappear. The key word here is indeterminacy. So what if the plane from Chittagong to Dhaka flies over the Sundarbans, or the president of the club arriving from London to Chittagong via Dhaka has his luggage custom-checked! These are small matters indeed, especially if one considers the breathtaking sweep of the novel that ranges an esoteric mix of people with their plans and perspectives against a grim landscape that offers no respite. Then there are the narrative voices and narrative frames that create their own layered texture. Indeed, as one reads on, the novel appears to be less about verisimilitude or purpose or design than about an infinite play of imagination where the disjunctive nature of experience creates its own discursive patterns. As the sudden appearance and disappearance of The Shadow--the mystery of which is never explained--suggest, Under a Tin-Grey Sari is basically about the imponderables in our life--the happenings and presences that one doesn't always see or feel, and can hardly predict but which silently and relentlessly hold on to their place, upsetting even our best laid plans. Thus, no one would probably raise any question about the authenticity of the sometimes improbable and bizarre experiences of the young crowd--including the Minisahib--because the characters, in the end, appear to be part of a pageant that simply keeps happening without forcing a conclusion. The fact that the setting is Chittagong--which is consistently rated by the narrator above Dhaka or Calcutta--lends an enchantment to the view, but one realizes that the limited space the city provides only makes the action that takes place in it all the more intense, and at times, anarchic. Chittagong is both esoteric and specific; these qualities do not cancel each other out: if anything, they reinforce each other. The story of Under a Tin-Grey Sari is not out of the ordinary, although some of its twists and turns are. Zeythi arrives from the hills (she is a Chakma) in a household where the old master with (west) Pakistani connections lives with his British-born wife and their children, and the young grandchild, and where Khalid the cook looks after the kitchen and dreams of Dhaka and a new and improved tandoori oven which will bring him luck. Khalid has friends, Iqbal the letter writer and Mohendra the chickenwalla, among others, while Zeythi pretty much keeps to herself and the Minisahib. Chittagong has a Anglo-Bengali and English crowd with expat Australians thrown in who find the club a good place to meet and drink and while away the evenings. There is a (west) Pakistani crowd and a Bengali-speaking crowd as well, yet surprisingly, the focus is squarely on the bunch of bearers in the club (the chief bearer Akram and the spitting bearer Mahfouz being the two more prominent ones). There are temptations for Khalid in the shape of women he meets at the Polytechnic (yes, he is quite a literate fellow) but he is firmly given to Zeythi, who meanwhile is attempting to come to turns with the vacuum left behind by the death of both parents. Khalid does invent the tandoor, but the president (referred to as ‘President-bastard’) steals the design, leaving Khalid distraught. After disillusionment in Dhaka, he falls sick and dies. He is buried at the Zakir Hossein Road graveyard with a headstone announcing that he was 'A wise friend educated in the simple and the difficult things in life.' The novel's story ends there, but it indeed begins from there too, as the dead Khalid is the narrator of the story. And as if a dead narrator is not enough to unravel the story's many mysteries and puzzles, Ashton presses into service Khan the Sabjantawallah as a super omniscient commentator, whose musings--as reported by Khalid--add to the novel's postmodernist narrative frame. The short (sometimes one and a half page) chapters, with elaborate titles, do a similar job. All told, Under a Tin-Grey Sari is a bravura tale told with gusto, and with a lot of empathy. It is a story that, despite its sometimes long-winded passages, amply rewards a close involvement by the reader with all its characters. Wayne Ashton will have won over many a reader with this novel, except perhaps the die-hard Jatiyatabadi sort, for he mentions the unthinkable fact that it was Sheikh Mujibur Rahman whose voice first proclaimed the independence of Bangladesh, and that Ziaur Rahman's proclamation came a good two days later, on 28 March, 1971. Syed Manzoorul Islam teaches English at Dhaka University.

|

|