Major changes in education policies: Are we ready?

The Ministry of Education has planned for a radical change in the existing curriculum from primary level to higher secondary level. Board Examinations like Primary Education Completion Examination (PECE) and Junior School Certificate (JSC) will be discontinued and there will be no opportunity for selecting disciplines (Science, Humanities and Business Studies) at the secondary level. New textbooks and a new assessment system will be introduced. The proposal has been put forth to start in 2022. After declaring the outline for the new curriculum, a serious debate took place about whether we are ready for this initiative or not.

When the education system of a country has to go through such experiments on a regular basis, it becomes extremely vulnerable. Generally, it is expected for a country's education system to undergo major changes every 10 years to adopt the changes of socio-economic perspectives and to cope with the enhanced educational technologies. That is why in the National Education Policy 2010, we see plans for the creative questioning system, PECE, JSC, primary education extended up to eighth grade, etc. But the National Education Policy 2010 has not been fully implemented till date. Even those that have been implemented have not been able to bring promising success. In other words, we have not got the expected results from the policies adopted in the past.

To understand why such new policies may not work out properly and why the previous policies did not work well, it is important to understand the limitations of the stakeholders related to these plans.

First of all, the quality of education in our privileged and underprivileged areas differs greatly. The perks of being privileged and having several options in hand have never been there for the students who are deprived of access to enough resources. That is why they do not have enough opportunities to adapt to the new curriculum, to begin with. For instance, in the last 10 years, only a handful of students from rural educational institutions have been able to understand the pattern of the creative question system. It is a serious doubt if Bangladesh has the number of resources needed at the grassroots level to introduce a whole new style of policy and has feasible plans to create proper check and balance between the educational institutions of rural and urban areas. If not, then the concept of inclusive education that we are moving towards is unrealistic.

Moreover, it will be a real tough job to provide better learning without having an adequate amount of expert teachers. Adding new strategies or subjects to the curriculum also requires that those who teach these topics in schools and colleges are themselves proficient in these subjects. Unfortunately a good number of teachers do not have such expertise. Due to the lack of proficient teachers at the grassroots level, a large number of students fail every year in ICT. This picture is not specific to any particular educational establishment, but to most rural educational institutions. This is why the check and balance system fails to adhere to the privileged and the underprivileged groups.

According to the new curriculum, a new subject related to mental health is being added, but most teachers do not even have a good notion of what mental health actually is. We have seen the inclusion of subjects like ICT in the past, but even after five years, there is still a lack of skilled teachers in this particular subject, which is reflected in the results of public examinations. So even after so many years, if students can't overcome the fear of subjects like ICT in rural educational institutions, there is very little possibility that this new subject will be absorbed by them.

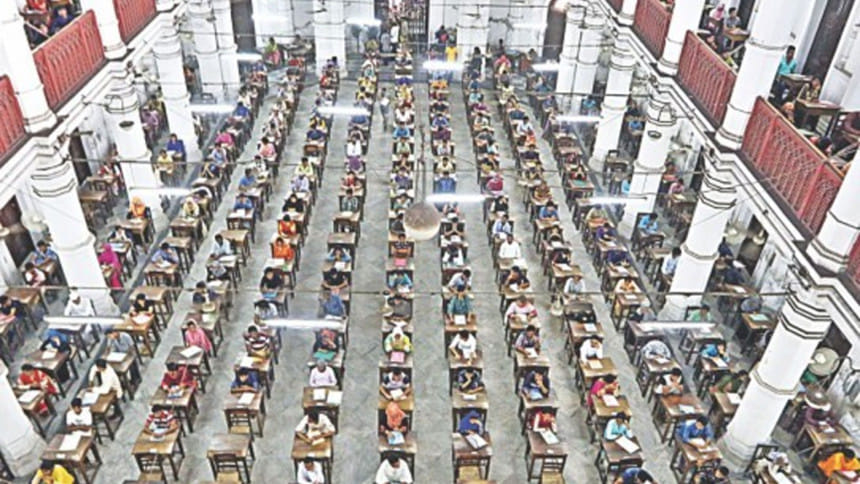

On the other hand, massive changes are going to be made to the examination system. Apart from annulling the JSC and PECE exams, the new policy seeks to measure student's achievement through formative assessment instead of summative assessment. From the pre-primary to the higher secondary level, learning based assessments will be introduced. Getting teachers acquainted with the formative assessment is a big burden. We do not have as many teachers as we need for it to be convenient enough for them to evaluate an average of 60/70 students in a classroom-based on their class performance. It is also unclear how to maintain impartiality during the learning-based assessment process. Moreover, in the past years, teachers used to have a certain percentage of marks in their hands, which is probably no longer practiced. There is no apparent outline of why this assessment process will work this time around. Even if we assume that teachers will be properly trained for this, the chances of a qualitative change at a large margin are slim. As our teachers do not like to experiment with new insights in the classroom and feel more comfortable in the traditional style of teaching and assessing, the addition of a new assessment process may be a total waste.

Rapidly modifying the system may not solve the problem at all. It is perhaps more important to identify the loopholes of the existing system and fix them first! Introducing new policies in the education system is important, but the real question is whether we have the capacity to implement these policies or not.

ASM Kamrul Islam is a student at the University of Dhaka.Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments