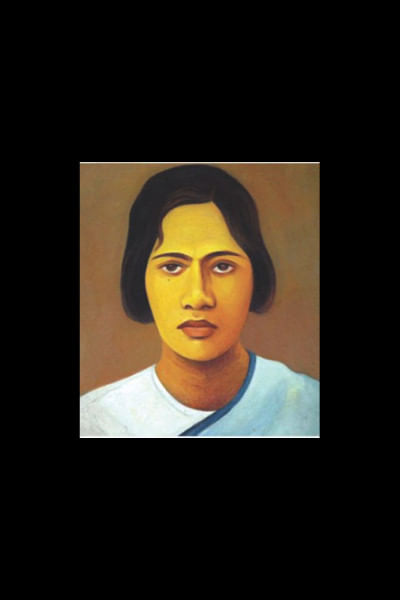

Pritilata Waddedar: Politics of remembrance

If you aren't familiar with Pritilata Waddedar or can't fathom why her achievements need to be celebrated and her death commemorated, blame the mainstream narrative of the Indian resistance against British colonialism that makes sparse mention of the first woman martyr of India's independence movement. While Pritilata is given a fleeting mention in history texts, Bollywood films have committed an even more grievous crime. They have distorted her role in the Chittagong Uprising, heavily focussing on an inaccurate portrayal of her as a sexual, romantic interest of the main lead, blatantly disregarding her political role as a revolutionary who played an active part in upsetting the balance of colonial power in India.

When Pritilata Waddedar sought to join the Surya Sen-led Indian Republic Army, women's entry into supposedly masculine spaces, like revolutionary groups fighting against British imperialism, was strictly restricted. Kalyani Bhattacharjee's Jibon Adhyayan explains that even though revolutionary nationalist groups called upon their female counterparts to join the cause by acquiring necessary physical skills, most of them followed a "programme of physical culture and social works", where women were taught "manly arts" like fencing, cycling and boxing, they were also asked to acquire "womanly" skills such as first-aid and nursing so they could essentially play a background role of caregiver to the male freedom fighters. As pointed out by Nirad C. Chaudhury in Autobiography of an Unknown Indian, this dual standard was also a form of rejoinder against the British colonial perceptions of the "effeminate Bengali". In fact, Masterda Surya Sen had himself asserted that even though he was not opposed to the idea of women joining the resistance movement, he never thought that they could be of much use except as "sympathisers and behind the scene helpers."

In this scenario, Pritilata and other female freedom fighters like Kalpana Dutta, actively worked to disprove the British emphasis on the low status of women in India, by evoking the image of the Goddess Shakti and urging women and the larger Indian society to take up arms and join their "brothers" in the fight against imperialism. Indian women were already on the forefront of the Swadeshi movement, as they boycotted foreign goods and marched in rallies, but their roles were largely relegated to such auxiliary tasks. Before joining the IRA, Pritilata joined Deepali Sangha, headed by Leela Nag, in Dhaka, which was set up with the express purpose of mobilising women to be politically conscious. However, Pritilata was not interested in the work that such women's organisations did. She understood that in order for her and other women like her to be considered equal to their male compatriots, she needed to be involved in direct combat. As Sarmistha Dutta Gupta writes in her article Death and Desire in Times of Revolution, published in Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), this desire in itself indicates that Pritilata had "accepted the division between the 'social' and the 'political' and internalised the ideological position that the work of women's organisations was 'social' and never equal in importance to the 'political work done by men'."

In an attempt to change this perception of women as the weaker, more vulnerable sex, Pritilata and Kalpana Dutta knew that they could not accept the position of "uninitiated" members that the IRA offered them and so were ready to prove that they could be instrumental in plans that involved direct attacks against the enemy force. Pritilata first met Surya Sen in 1932, and the leader noted that even though it was raining heavily, "both when she came and when she left and it was muddy all around, not even once did she stumble. Just this one meeting was enough to convince us of these strengths of hers" (Nirmal Sarkar, Surya Sen O Pritilata Rachana Sangraho). Pritilata had to perform overtly "masculine" tasks, such as scaling walls, hiding in jungles and diving in ditches, without showing any sign of discomfort or fear to prove that she was capable to handle arms and would not flinch in the face of imminent death.

Her first major job after joining the IRA was to offer emotional support to freedom fighter Ramkrishna Biswas, who was arrested and sentenced to death for the assassination of Inspector Tarini Mukherjee. Disguised as his sister, Amita Das, Pritilata met Biswas 40 times until his death, and wrote that she felt "ten times more inspired to fight for freedom" after meeting the revolutionary on death row. She also took part in attacks on British Telephone and Telegraph offices and the capture of the reserve police lines, disguising herself as a man to join her fellow fighters.

In essence, Pritilata had to 'defeminise' herself to establish that she was equal to her male counterparts, which, as explained by Sharmishta Das Gupta, went against her more "gentle, introverted, `feminine' persona, as she liked to write, could sing well and had a literary bent of mind."

Young freedom fighters like Pritilata also had the added responsibility of preserving their "chastity," and ensuring that their moral dignity was preserved at any cost. Thus, even though they might have felt an attraction toward any man in their group, they had to keep it to themselves, without revealing their feelings to even the subject of their admiration. In her piece titled ` Pritilata wrote about her relationship with Nirmal Sen, Surya Sen's second-in-command, with whom she spoke of her meetings with Ramkrishna Biswas as well as how she negotiated her feelings towards her family and her motherland. In fact, when Sen was killed in a sudden police attack, Pritilata could hardly stop herself from running to him when she heard his cries, as she wrote, "I just couldn't bear his heart-wrenching cries. If I could only just be with him once in those last minutes, I don't know what he might have told me. But God didn't let me see him before he breathed his last." Yet, their feelings toward each other was mostly kept within themselves, as the environment within revolutionary groups was strictly de-sexualised, and every member was aware that they had to marginalise all other loves in view of their love for their country; in short, these revolutionaries were only permitted to function as political beings.

When Surya Sen planned an attack on the Pahartali European Club, which had a signboard that read "Dogs and Indians not allowed," it was decided that a woman would head this mission. After Kalpana Dutta was arrested seven days before the attack, Pritilata was assigned to lead the operation, and she was accordingly trained for this in Kotowali. On September 23, Pritilata headed towards the club with her eight-member team. Each member of the group was given potassium cyanide and Pritilata expressly requested Sen to allow her to swallow the pill if they were arrested. She dressed as a Punjabi sardar on D-Day and attacked the club at around 10.45 pm. The attack was a success but Pritilata was injured when a policeman shot at her. In order to avoid getting arrested by British police officers, she swallowed cyanide and breathed her last, aged 21, almost instantaneously.

In "Long Live Revolution," cited as her last testament found by the police on her body, and later distributed as pamphlets by members of the IRA in Chittagong after the Pahartali attack, Pritilata urged every woman of India to "get themselves ready to face all dangers and difficulties and join the revolutionary movement in their thousands." She had further declared that if women "are yet less fit it is because they have been left behind."

Pritilata's decision to join the movement was a conscious political choice; her intention to die a martyr was well-planned and properly thought-out. It is thus saddening when we see such a woman being relegated to the role of a romantic interest whose only reason for joining the resistance movement against colonial British was her attraction toward another freedom fighter. Pritilata was much more than just a nurse or a sexual object as portrayed in the media; she wanted her death to mobilise women to join the fight against imperialism, to prove detractors wrong about their abilities. In a patriarchal society where only the achievements of men are mostly heralded in our master narratives, Pritilata's role might have somewhat been diminished to a supporting one. In our small, insignificant way, we salute the woman who fought valiantly for her country and sacrificed her life so that voice of a woman would matter in the narratives written by men.

The writer is a journalist at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments