A state in ferment, a newsman in reflection, a principle under assault. . .

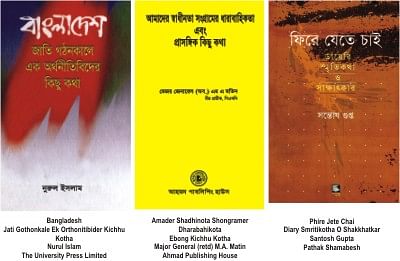

Nurul Islam was not content to be on the stands while the history of Bangladesh was being forged bit by significant bit. He was a participant. And that participation dates back to the early 1960s when, as part of a team of young Bengali economists in Pakistan, he played his due role in the development of what would later become known as the 'two economies' or two distinct systems theory as advocated for East and West Pakistan. Sure, the powers that were (and their symbol was General Ayub Khan) could not be receptive to the idea. Implicit in the idea of two economic systems for the two wings of Pakistan, or so reasoned Ayub and the entrenched class of West Pakistani rulers, was the eventual secession of the Bengali east from the more prosperous west. But that did not preclude President Ayub from summoning Islam and his friends to a meeting, to ascertain the nature of their observations. The young Bengalis put the argument before the military ruler as best they could. Ayub listened, after which no more was heard from him.

That is how this revealing work, translated in abridged form from the original English, gets into a pace. And Nurul Islam is eminently placed to take readers back to some of the more stirring of times in the history of the Bengalis because, beginning in 1969, he worked closely with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on the modalities of implementing the Six Point formula for regional autonomy in Pakistan. Islam, ultimately to serve as deputy chairman of the Bangladesh planning commission, retraces the early steps toward what would in the end take a turn toward Bengali political independence. In Mujib, he notes, there was not only an inspirational political leader but also an individual who had his finger on the finer details of policy. He was pretty certain about what he wanted out of his Six Points; and with individuals like Nurul Islam, Anisur Rahman and Rehman Sobhan, he knew that the points could be fleshed out and offered to the whole of Pakistan as a methodology upon which politics could operate in the future. The future father of the Bengali nation impressed Islam hugely. In similar measure, he found Tajuddin Ahmed remarkable in the degree of wisdom he brought to bear on his scrutiny of the Six Points.

That was in the late 1960s. By early 1971, as popular expectations of the Awami League ascending to power in Pakistan rose, it was Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who made matters clear for all. He understood, having been part of the history of Pakistan since its founding in 1947, that the West Pakistani establishment would go to any length to undermine a Bengali prime minister at the centre. And then came another truth, again in light of Mujib's experience. Having observed supposedly committed Bengali politicians ending up crossing the fence all too often and so undercutting the cause, he needed to make certain that this time around (and that was in the post-1970 election period) no Bengali betrayed the cause. Hence the public oath-taking at the old Race Course on 3 January 1971. The Bengali leader was making his position clear. In the first place, there would be no point in taking charge of Pakistan unless the Six Points redefined the nature of the state. In the second, the focus of the Awami League would remain East Pakistan. Mujib had little thought of his taking over as prime minister of Pakistan. Indeed, he made it be known that if necessary, Syed Nazrul Islam or Tajuddin Ahmed could move to Islamabad while he presided over the rejuvenation of Bangladesh, as he had begun calling the eastern province of the country.

Nurul Islam's analyses of post-liberation Bangladesh bring into sharp focus the contradictions and conflicts that challenged the new state in its early days of freedom. Obviously, the role of Tajuddin Ahmed, his decline in particular, comes into sharp focus in the narrative. Prime minister of the Mujibnagar provisional government in 1971, Tajuddin as finance minister in Bangabandhu's government refused to have anything to do with the World Bank's Robert McNamara when the two found themselves together in Delhi in February 1972. McNamara's eagerness to speak to Tajuddin was rebuffed by the latter, on the ground that McNamara had been one of the prime architects of the Vietnam war and also because of the Bengali politician's belief that McNamara's role regarding Bangladesh in 1971 was close to that played by President Nixon and Henry Kissinger. Eventually, though, Tajuddin was compelled to eat humble pie. From Delhi, McNamara arrived in Dhaka even before Tajuddin did, met Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and worked out the outlines of future World Bank involvement in Bangladesh.

In October 1974, only days before he was forced out of the government, Tajuddin Ahmed travelled to Washington, to talk to McNamara on the widening nature of assistance the World Bank would provide to an increasingly hapless Bangladesh. Nurul Islam recalls his last meeting with Tajuddin, in late 1974, as rumours went around of intelligence personnel keeping an eye on the fallen leader. It was one of those times when Sheikh Fazlul Haq Moni, nephew of the prime minister and inveterate foe of Tajuddin, was in the ascendant. Islam recalls Moni's incendiary editorial in his Banglar Bani newspaper. It was a frontal assault on the planning commission as it was then constituted. When Islam showed Mujib a copy of the editorial, the prime minister was visibly upset. Islam dwells on the style Bangabandhu employed in his administration of the state. He makes no attempt to conceal his sentiments. Government ministers, he notes in a matter of fact way, were paralysed to a point where they could not make important decisions without first referring matters to the prime minister.

Nurul Islam's reminiscences are a tale of the past come alive. The assumption of office by Mujib as prime minister and then the slide downhill, owing to factors straddling the local as well as international, are a reminder of the trauma the government went through in the formative years of independent Bengali nationhood. A lost cause? More like a bruised one.

SANTOSH Gupta died almost five years ago. With his passing it was once more time for Bangladesh's journalism to take a fresh beating, for Gupta was one of the more committed and conscientious of media personalities in the country at a time when many of his peers were falling by the wayside. He was a poet, thinker and diarist. Above all, he was a journalist, a constantly cigarette-smoking one. Those who knew him did not fail to spot the naturally human elements in him. Those who did not (and this last group comprised the generation that came long after Gupta's) found him aloof in his dealings with them. Or could it be that his severe demeanour was a discouragement for these young?

Whatever. But what we now have before us is a posthumous collection of Santosh Gupta's thoughts as he left them in his diaries, notes and articles in a long career. Much of his life was spent at Sangbad, though the Azad too was a path that led him to his journalistic objectives. It was a career that was enriched by Gupta's membership of the proscribed Communist Party. No one had any clue that he was a card-carrying communist, though many were aware of his sympathies for the communist cause. As a lower level official at the office of the inspector general pf police in 1949, Gupta could have provided his party comrades with inside information on the doings and movements of the police department. In what many would today consider an old-fashioned attitude to political commitment, he refused to indulge in what he thought would be a breach of faith. His communism was his alone; and his job was an entirely different matter.

And then the police took him, along with others, into custody. A surprised IGP informs him that there must have been a mistake, for Gupta, a cog in the police wheel, could not be a communist. Gupta's response to the IGP's puzzlement is typical of the man. He tells the man he has so long worked for that there had been no mistake, that in fact the police knew about his politics and so had produced him at their office. That was the beginning, where jail is concerned, for Gupta. He was to be freed and then would go on to other jails because of his communistic preoccupations. By the late 1950s, though, he would settle down --- as a professional journalist, a job he persevered in doing till the end of his life. This compilation is thus a window to his life, his thoughts and to a world he looked forward to. In a bigger way, it is a commentary on the times he shared with so many of his compatriots and peers. And those times were excruciatingly painful and yet full of the promise of possibilities. Gupta belonged to a generation that was traumatized by partition (his family chose, though, to stay back in Muslim East Pakistan rather than move to the safer, more liberal confines of West Bengal); his generation suffered through the persecution of communists by the state. Gupta lived through the horrors of the communal riots in 1964, when the Ayub-Monem Khan clique went every possible way to whip up mayhem between Muslims and Hindus on a grand scale. And then, surely, was the all-encompassing darkness of the Pakistani pogrom in 1971. Gupta would make his own contribution to the war. He would link up with the Mujibnagar government.

The diaries, stretching from 1990 through 1999, are a fascinating part of the collection. And they are because of the subtlety and the allusions that Gupta employs in them as he relates incidents and events which have touched him, for better or for worse. His ruminations over matters at his workplace, Shaukat Osman's dropping by at his residence with a couple of books for his daughter, his struggle to say farewell to smoking, et al, throw up the human dimensions of Santosh Gupta's character. He was into poetry, not just composing it. He took other men's poetry in his stride and gave it a fresh new dimension through his translations. On a day in March 1992, he reads Keats' La Belle Dame Sans Merci. And feels good about it.

READING M.A. Matin's work (and it was first published in 2000) will jolt you, once more, into awareness of how the very essence of Bengali nationalism has been undercut in this country since the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Matin is a retired military officer, a freedom fighter and has held high positions in government, the last one only recently. Which is why it comes as a shock knowing of the degree to which he flails away (and he does it endlessly) at the secular concept that went into the struggle for Bengali liberation in 1971.

It is a work that makes you sad, for it seeks to wrench the Bengali away from his moorings and back to the obsolete two-nation theory propagated by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League in the 1940s. Matin makes it a point to stress, at repeated intervals, his respect for those who died in the struggle for Bangladesh. But where the spirit of 1971 is concerned, he unabashedly informs readers of the Muslim identity of the people of this country. He does not regret at all the dark truth that the four fundamental principles of the Bengali state were undermined by Bangladesh's first military ruler Ziaur Rahman. As a matter of fact, Matin's happiness at the act is palpable. The insertion of the Koranic phrase 'Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim' in the constitution, in absolute contravention of historical reality and in gross violation of the constitution, is what he celebrates. And it extends to the clear enthusiasm he demonstrates when speaking of General Ershad's imposition of Islam on Bengalis as the religion of the state.

The old, stale untruths are vociferously stated in this slim work. Ziaur Rahman declared the independence of the country. Worse, the government led by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman turned out to be, in his view (and it must have cheered the diehard rightwing), a puppet of the Indians. Briefly, Matin peddles the notion that between 1972 and 1975, it was a vassal state of India that Mujib presided over. His visceral dislike of Bengali intellectuals comes through constantly, the implication of his sentiments being that these men and women (truly the symbols of a dynamic Bengali modernity) are beholden to their counterparts in West Bengal for the evolution and propagation of their thoughts. It is a dangerous sentiment. Matin's belief, misplaced though it is, is that Bengalis on the two sides of the divide have really nothing to share with one another. Insularity is therefore all. And despite 1971 and the retreat of Pakistan, it is still 1947 that should be the Bengali's claim on history.

This work explains, as it were, the wider framework in which Bengali values have consistently and systematically been pushed over the brink since August 1975.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments