Glimpses into the making of a national titan

The history of the world is but the biography of great men.

--Thomas Carlyle

A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history.

--Mahatma Gandhi

To do anything great, one has to be ready to sacrifice and show devotion.

--Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

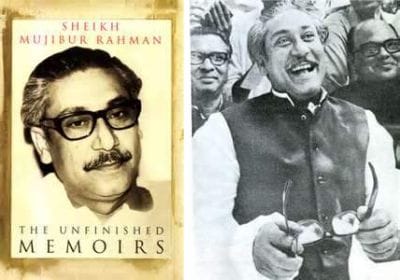

The Unfinished Memoirs is no ordinary book by a run-of-the-mill author. It is by our national hero, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (1920-75), the founding father of Bangladesh; this is the man who rewrote the course of South Asian history and who, fighting all odds with his singular devotion and bravery, as well as an unquenchable faith in his mission,created a separate national selfhood for us, we Bengalis in what was once a part of undivided British India, later becoming East Bengal and East Pakistan, and now Bangladesh on the basis of our linguistic identity. The book is written in simple, eloquent prose, using a linear narrative, in which the author recounts the shaping experiences from his formative years that were to mould not only his own destiny as an individual and a leader, but also the destiny of an entire people. It traces Mujib's political journey from 1938, the year that a young school lad from Gopalganj first met Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (1892-1963), who was later to become his political “papa,†to 1955, the year that Mujib took up the helm of the Awami League as its General Secretary.This was the party that would eventually lead us to the independence movement in 1970 again, under the leadership of none other than our giant, Sheikh Mujib, who was not just a political colossus, but who, standing tall and with a commanding physical presence, was literally larger than life.

The book is “unfinished†because it covers only the first 35 years of Mujib's life. It gives us a glimpse of Mujib's family history: how he grew up in modest circumstances in his village home in Tungipara and, later, Gopalganj; it also details his early schooling, interrupted frequently due to illnesses, until he finished his matriculation and went to Calcutta. It also gives us an extensive account of how Mujib began his political career under the loving and intimate guidance of his “guru†Suhrawardy; how he joined the Muslim League and took up the cause of Pakistan; how he fought tooth and nail against the heinous colonial rule for national independence; and how he lived through the nightmarish communal violence that battered the subcontinent prior to independence, turning Bengalis against one another on religious lines and spattering the roads of Calcutta with the blood of their people on many occasions, but most significantly on Direct Action Day (1946). The book also records the emergence of a language movement in East Pakistan when, after independence in 1947, the Pakistani junta refused to accede to the call to make Bengali a state language and the role that Mujib played in fomenting and leading the movement, sometimes from a jail cell.

In addition, the book recounts how the seed of the dissolution of Pakistan was sown soon after its creation, as its national future was hijacked by a handful of self-indulgent, money-mongering political mafia, and as West Pakistan began rehearsing the repressive practices of the British colonisers on the Bengalis of East Pakistan. However, what is missing from the book is the most glorious chapter of Mujib's life, when his party won the 1970 elections in Pakistan by an overwhelming majority, and, after being denied office through a conspiracy by some witless West Pakistani leaders, led East Pakistan to a liberation movement, eventuating in the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The book remains incomplete mainly because Mujib's life was unexpectedly and most tragically cut short by a military coup in 1975 in which he was assassinated, along with several of his family members, by a group of thankless and cowardly military officers.

The book was written when Bangabandhu was sent to jail for the umpteenth time in 1966. He wrote it in a jail cell perhaps the only time for a leader too engrossed with the people and their future, to look back and reconstruct memories from the past. The author begins by explaining how he commenced writing the book: tentatively, unsure of its purpose, but actively encouraged by his wife, Renu, and his friends. “Will the public benefit from the story of my life?... What if I wasn't able to narrate events skilfully? Would it be really awful if I wrote down whatever I could remember?,†Mujib mumbles in his characteristic modesty, before taking up a notebook given to him by his wife and begins his coming-of-age story. We have to be grateful that in spite of his initial scepticism and faltering, Bangabandhu finally decided to write the memoir, because it is not only a priceless historical document that tells us the story of the creation of Pakistan and the beginning of the creation of Bangladesh, but also an invaluable personal document that recounts the life, personality, character and worldview of our greatest national luminary.

On a personal level, Mujib emerges as a simple, sincere, honest, devoted, loyal, loving, compassionate and brave individual, who was idealistic yet pragmatic, ambitious yet selfless, determined yet humble, and, above all, always unwavering and incorruptible in his faith in himself, his people and his principles. He would invariably stand by his people and fight for their rights and privileges, and in return he enjoyed their unconditional love and confidence. There are many incidents in the book in which Mujib stands up for a cause or against an act of injustice on an individual or a group of people, risking his own life or the potential of being hauled off to jail. But he was never cowed or deterred by fear in his fight against injustice a quality that automatically made him a people's hero.

Likewise, there are instances when the people came spontaneously to his aid after he was wronged or abused by the authorities. One such example stands out and deserves mention here. It was in 1954, when Mujib (still only 34 years old) was contesting in an election from the Gopalganj constituency against his arch enemy, Wahiduzzaman. The government machinery was zealously working for Wahiduzzaman, a pro-establishment candidate, and the pseudo-religious bigots had also joined forces with him, declaring Mujib an enemy of Islam. Wahiduzzaman was rich and had piles of money to splash on his campaign, but Mujib had little or none. His only hope was the people; he knew in his heart of hearts that the people would be there for him. So he began his rounds of meeting them, going from village to village.

One day, during one such campaign visit, he came upon an old lady who was virtually destitute. She had nothing except for a big heart, swelling with love for her young hero, the magnetic Mujib. His name was the equivalent of a magic spell for her, and as she had heard that Mujib was to visit her village, she kept waiting to meet this valiant leader of the luckless and the poor. Finally, when she saw him walking past her shack with his entourage, she held him by the hand and led him inside her dilapidated home and, offering him a glass of milk and her last coins for his election campaign, said in a tender voice, surging with emotion, “The prayers of the poor will be with you.†If souls can meet, here was a meeting of two souls, and Mujib was visibly overpowered by the occasion. He responded to the woman's honest love with equal candour, as tears trickled into his eyes. “When I left her hut my eyes were moist with tears. On that day I promised myself that I would do nothing to betray my people,†Mujib affirms a pledge, indeed, which he kept not only till the last day of his life, but eventually sealed it with his own blood and the blood of his loved ones.

It is no secret that, like any other political leader, Mujib sought power, but it was never for personal gain or at the expense of his ideals. He wanted power to serve his country and to alter the fortunes of the insulted and the humiliated in society. However, like many of his fellow politicians or even members of his own political party, Mujib was never power-hungry, or rather, he never craved for it in a wrongful way. He was a true patriot, for whom service was the ultimate mission. He was wary of politicians “who had no principles or ideals,†for, as he writes in a tone of revulsion, “They were in politics for personal gain and they did not really care about their country.†In a reply to Abdus Salam Khan, a senior colleague in the party, ironically also from Gopalganj, who seemed constantly embroiled in politics of conspiracy, and who coveted power, Mujib derisively comments summing up his own outlook vis-à -vis that of the vast majority of self-indulgent, hoggish politicians around him: “The nation will not benefit from having unscrupulous people in power. That can only help men who are interested in their own advancement….We might attain a position of power one way or the other, but we won't be able to do anything for the people that way and in any case power got by expedient means will soon evaporate.â€

Bangabandhu's moral and political philosophy was made up of four intersecting and overlapping principles: Humanism, Nationalism, Socialism and Religious Inclusivism. First and foremost, he was a humanist; he loved mankind. Gandhi, in his characteristic spiritual expansiveness, once said, “You must not lose faith in humanity. Humanity is like an ocean; if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean does not become dirty.†This was Bangabandhu's ideal too. Thus, in spite of his occasional frustrations with the selfish and vested-interested lot surrounding him, he never despaired of humanity, but instead devoted himself wholeheartedly to the upliftment of the general human condition any way he could.

However, Bangabandhu's humanism found its most concrete manifestation in his nationalist ideals. In a celebrated statement inscribed as the book's epigraph, intertwining the two, Bangabandhu saliently said, “As a man, what concerns mankind concerns me. As a Bengalee, I am deeply involved in all that concerns Bengalees. This abiding involvement is born of and nourished by love, enduring love, which gives meaning to my politics and to my very being.†This immediately explains why he was so vigorously drawn to political activities even as a young boy. It was the time of the Swadeshi movement, when India was trying to come into its own by driving out the “white-skinned parasites†who were fattening their own country and nation by feeding on Indian bodies and blood. “I began to harbour negative ideas about the British in my mind. The English, I felt, had no right to stay in our country. We had to achieve independence. I too became an admirer of Mr Bose and started to travel back and forth between Gopalganj and Madaripur to attend meetings. I also began to mix with the people in the Swadeshi movement,†Mujib writes in the memoir, recalling from the time of his school days.

It ought to be pointed out here that Mujib's nationalist philosophy developed in three stages: he began as a secular nationalist, being influenced by Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das (1870-1925) and Netaji Subhas Bose (1897-1945); however, disillusioned by the religious strife between Hindus and Muslims during this period, he got drawn into religious nationalism; finally, prodded by the indifference of the Pakistani rulers towards the Bengali language and their unremitting injustice towards the Bengali-speaking people of East Pakistan, he became a resolute linguistic nationalist.

It was during the second phase of his nationalist struggle that Mujib became a champion for the creation of a separate homeland for Muslims in Pakistan. “I believed that we would have to create Pakistan and that without it Muslims had no future in our part of the world,†Mujib writes in the book, and adds at another point, “I believe that if we don't attain Pakistan Muslims will be wiped out.†Induced by this thought, he fought for Pakistan under the leadership of Suhrawardy and Jinnah (1876-1948), until the country came into being in 1947.

This was the young Mujib, dreamy and full of idealism, but still learning the ropes of his trade. However, his dreams of attaining a land of promise for the Muslims of the subcontinent, where they would be free from inter-communal strife and live in mutual fellowship and fraternity, were dashed soon after the inception of Pakistan. He realised that the only change achieved by the birth of Pakistan was that “the white-skinned rulers had been replaced by dark-skinned ones.†Except for that, it was business as usual. Oppression, exploitation and brutality continued on a daily basis, albeit the perpetrators now were fellow Muslims. Pakistan had two wings, East Pakistan and West Pakistan, and the Bengalis of East Pakistan formed the majority in the country, but “the capital, military headquarters, all the government positions and the bulk of the country's trade and commerce†were in West Pakistan. Bengalis asked to make their language one of the state languages of the country, but this was denied in the most vicious wayby firing upon and killing several innocent Bengalis,merely for championing their mother tongue. The call for the autonomy of East Pakistan in the face of mounting tyranny and injustice, was similarly met with autocratic resistance and apathy.

All these brought a new awakening in Mujib, marking a new phase in his nationalist struggle. He now became a language nationalist. Leaving the Muslim League, he and his followers formed a new party with Maulana Bhashani soon after the formation of Pakistan: Awami Muslim League, renamed Awami League a few years later, to reflect the party's non-communal struggle for the Bengali language and autonomy of East Pakistan. The party was built on the ideologies of nationalism, secularism, socialism and democracy principles which were also embodied in the constitution of Bangladesh, when the country came into existence through a bloody liberation war in 1971.

It is during this period that Bangabandhu overcame whatever seeming contradictions he may have had with regard to religious unity and inclusivism. Even when he was actively involved in the struggle to create a homeland for Muslims, he still believed, paradoxical as it may seem, that Pakistan would be a democracy in which “people of all faiths, irrespective of race and religion†would be able to live together, enjoying “equal rights.†But now religion was no longer part of his political agenda; his focus was squarely on uniting the people of East Pakistan, irrespective of their religious identity. He was still a practising Muslim no doubt, praying and reading the translated Qur'an on a regular basis, but he refused to be circumscribed by his religious identity. Thus in a conversation with Chandra Babu, a fellow politician from Gopalganj, when the two were in jail together in 1951, Bangabandhu affirms, “Don't worry, I… treat people as people. In politics I make no distinction between Muslims, Hindus and Christians; all are part of the same human race.â€

Mujib's humanism was also characterised by his faith in socialism. He was of the view that socialism helped to create an egalitarian society by healing social disparity and making the playing field level for all its members. It was a moderate philosophy, situated halfway between the antithetical ideals of communism and capitalism, and therefore, Mujib rationalised, best poised to bring world peace. Capitalism was an instrument of exploitation for the rich and the powerful; it was used as a tool by the colonisers to plunder the colonised societies. Hence, to protect the masses from being abused by capitalist hawks and to ensure social harmony, postcolonial societies should abdicate from capitalism and espouse socialist principles. Bangabandhu explains this idea in the book in the following words:

I myself am no communist; I believe in socialism and not in capitalism. I believe that capital is a tool of the oppressor. As long as capitalism is the mainspring of the economic order, people all over the world will continue to be oppressed. The capitalists were quite bent on waging a world war to achieve their goals. People from newly liberated countries had an obligation to come together to work for world peace. Those who had been bound in chains for ages and those whose wealth had been looted by imperialist forces now needed to concentrate on building their countries and would have to devote all their energies into ensuring the economic and political freedom of the masses. It was vital to build opinion in favour of world peace.

The book reads almost like a who's who in Bengal/Pakistani and post-independence Bangladeshi politics.Even lay readers will be able to identify many of the names featuring in it, such as Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Sher-e-Bangla A.K. Fazlul Huq, Maulana Bhashani, Liaquat Ali Khan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Khawaja Nazimuddin, Abdus Salam Khan, Ataur Rahman Khan, Fazlul Quader Chowdhury and Tofazzal Hossain a. k. a. Manik Mia. They, and many others mentioned in the work, are like household names in Bangladesh; however, not everyone enjoys the esteem and confidence of the narrator. The book is told from Mujib's point of view, and the good or bad of the characters is subsequently based on his judgements about them, which are not necessarily always objective or neutral. Mujib was a shrewd observer of human nature, and he seems to have an opinion about almost every character in the book, which, as Buddha said, is also a common human habit.

Apart from the narrator himself, two other characters remain conspicuous throughout the memoirs, one by his recurrent presence and the other by her absence. The first is Suhrawardy, whom Bangabandhu consistently glorifies as someone honest, affectionate, benevolent and heroic, and emerges as the hero's hero in the book. The second is Bangabandhu's wife, Renu bold, selfless, courageous and loving, but always in the shadows, and appears rather like an unsung hero.

Bangabandhu's love and veneration for Suhrawardy remains a constant theme in the narrative. Again and again, he affirms his trust in Suhrawardy, asserts his loyalty to him and heaps unqualified praises on him. He confesses, “I was completely devoted to Suhrawardy,†and adds elsewhere in childlike simplicity, “Indeed… every day of my life I was blessed with [Suhrawardy's] love.†In one of his many tributes to Suhrawardy, for example, Bangabandhu writes:

Mr Suhrawardy was a generous man. There was no meanness in him and he wasn't influenced by partisan feelings or prejudices. He did not believe in cliques or coteries and did not try to work through factions. If he found someone eligible he would trust him fully. He had tremendous self-belief. He tried to win men's hearts through honesty, principles, energy and efficacy.

This is high praise, indeed, from one leader to another; but it says as much about the speaker as about his political guide. It shows that Bangabandhu was steadfast in his allegiance to the man who had inducted him into politics; that he was himself inherently honest, energetic and ethical and, therefore, had no qualms in attributing those qualities to his political mentor and father-figure.

However, I consider Renu the best and most admirable character in the book, even better than Mujib's icon, Suhrawardy. She is devoted, dignified, loyal, loving, selfless, calm, forgiving but at the same time tough, tenacious and brave. She hardly had the opportunity to live a happily married life with her husband, because while Bangabandhu was chasing his dream for the country and the people in Calcutta or Dhaka, Renu had to live all by herself, taking care of the household, Mujib's ageing parents, and their own two little children, Hasina and Kamal. Yet she was never unruffled by the course of events. In addition to the loneliness, she also had to withstand the anxiety of her husband often being sent to jail, sometimes for months or even years, but she took it all in her stride. Without her full-hearted devotion and sacrifice, Bangabandhu could never have reached out to realise the dreams he had conjured for himself, the people and the nation. Swami Vivekanada once said, “Husband and wife are the two wings of a bird.†Renu was the wing that enabled Mujib to float and fly like a blithe spirit into the sky.

The book comes with a preface, a political profile of Bangabandhu, some illustrative notes, a few images of Bangabandhu with his family and colleagues, several facsimile pages from the manuscript, bio snippets of several prominent political figures discussed in the book, and an index. They are all very useful, and help to complement the author's growing-up narrative. The Preface, by the author's daughter who features as a little girl in the book, and who is currently the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina is particularly useful as it informs readers of how the notebook in which the memoirs were recorded went missing for several years, until it was accidentally discovered by the family in 2004, coincidentally the same year that Hasina herself survived an assassination attempt. “It was as if a light had suddenly been sparked in the midst of darkness,†Sheikh Hasina writes in the Preface, to express her joy at the turn of events.

A word on the book's translation. This review is based on the translated edition of Bangabandhu's memoirs, and it reads so easily and naturally that had I not known that the book was originally written in Bengali, I would have automatically assumed that the book was authored in English. The prose in it is limpid, lucid, fresh and highly readable. Certainly it has been translated by one of the most capable hands in the country.

I would recommend the book to anyone interested in the political or cultural history of Bangladesh or South Asia, or in the auto/biography of significant world leaders. It will allow us a renewed understanding of how Pakistan came into being, who were the major players in the movement, and how Bangladesh was in the process of becoming a nation in its own right within a few years of the formation of Pakistan. It will also give us a full picture of the role Bangabandhu played in these historic events, and thus dispel any disinformation we may have about the history of the creation of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments