Prof. Razzak: Anti-hero, mentor

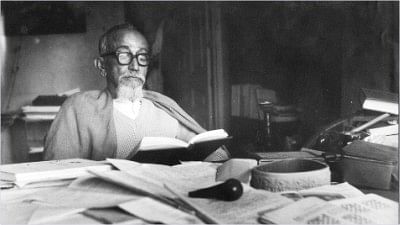

Photo: Nasir ali mamun

Professor Abdur Razzak (or in language typical of South Asia, "Razzak Sir") did not, formally, teach me a lot about political science, but he did, informally, teach me much about life. He taught me about personal dignity, about professional integrity, about moral authority. He taught me about making individual sacrifices, about relative indifference to material possessions or social status, about earning your respect from others through example and humility rather than shrewd machination or opportunistic compromises. He taught me about the pleasures of a sophisticated and enlightened mind, about the thrill of acquiring knowledge, and about the passion that animates a scholar's soul. He opened for me a world of books, ideas, beauty, and made me fall in love with it. He LIVED the life of a mentor and inspired others not through his position as a professor, but in spite of it.

Being requested to write about him is, undoubtedly, an honor. It is also a challenge. I am fully aware that I, presumably one among many others, can claim the status of being his "sneho-dhonno" or blessed by his affection. But that does not make my task easier. Without access to his un-submitted dissertation which I had the opportunity to peruse a long time back; or the slender publication attributed to him entitled "Bangladesh: State of the Nation" or the slightly quirky but adulatory book about him by Ahmed Sofa (Jodipo Amar Guru); or the occasional insightful essays by Shelley bhai (Mizanur Rahman); or the extended interviews he granted to Sardar Fazlul Karim Sir; or elliptical references to him in some writings of Hasnat Abdul Hye; or be able to compare notes with, or pick the brains of, others who probably have known him for much longer periods of time and may recall him much more vividly than I do, puts me at an enormous disadvantage. Here, in the wintry wind-swept bleakness of the upper mid-western prairies, I am trying to define my recollections of him, of specific things to grasp, of honest judgments to make. All I have are distant events, frayed conversations, and decaying memories. I feel like a prisoner in Plato's cave, and Razzak Sir's shadows are taunting me.

At the outset it should be pointed out that most memories are unreliable. They are vulnerable, contingent, and often treacherous. Elizabeth Loftus in her pioneering research has pointed out the frailties of memory and how it may be repressed, reformulated by others, or simply corrupted over time. How well, and how completely, do we actually "own" our memories given the distortions caused by the ambiguities of language, interventions of intermediate interlocutors and the swirl of over-riding events?

It should also be borne in mind that most memory tends to be political and may involve selection, partition and, at times, invention. We not only filter out relevant information according to our interests, but at times, we actually create an appealing fiction simply because it is what we wanted to have happened.

Finally, memories, at times, may be self-serving. In presenting our recollections of others we frequently end up telling more about ourselves than about the person we are writing about. The memorialized is no longer the subject of the essay but merely a platform for our own self- merchandising. We insert ourselves into events in which our participation was minimal, conversations where our contributions were dubious, and narratives into which our locations were peripheral, in obviously exploitative renderings.

All memories should be subject to textual deconstruction, where language, stories and recollections may be adequately scrutinized. The problem of writing about one who has passed away is that one can neither verify, nor even be challenged. It is like being presented with a tabula rasa and we can read our own script into it without any requirements of accountability or even objectivity. The task, apparently, becomes easier, but for one concerned about historical accuracy and ethical clarity, it is fraught with moral and empirical risks. This becomes all the more problematic when one writes about an extraordinary person (that Razzak Sir undoubtedly was). How should one balance celebration and criticism, at what point does sincere praise become fawning flattery, how does one extricate the man from the myth, and should one? I think these thoughts because, I KNOW, he would have wanted me to engage in some self-interrogation before writing on anything.

I do remember (here we go) that when I would pester him for advice on scholarly writing his answer was usually delivered in three parts. First, was the very Socratic "know thyself", second "know your subject" and finally, "be honest". In this exercise about him I will probably fail on all three counts. First, it is very difficult to "know myself" in the context of the formidable influence of Razzak Sir on my life, and my extended struggle to escape his long shadow. Second, it was always a challenge to know him as a subject because he would be deliberately elusive and allow only tantalizing, though at times telling, glimpses of himself, preferring to be the enigmatic private scholar he was rather than the activist public intellectual we wanted him to be (like Munir Chowdhury, Ahmed Sharif, Serajul Islam Chowdhury, Rehman Sobhan, Badruddin Umar and others). And finally, how dispassionate in my honesty can I possibly be in writing about the role model I had always wanted to emulate?

I was his student. I had classes with him in 1968 and 69. In my second year he was my tutorial master for a year as well. His lectures, when he chose to deliver them (which were not often), were almost whimsical, usually meandering, very seldom "on topic". Our tutorial seminars and assignments were unfocussed and inconsistent, more routinely missed than held. His writings were virtually nonexistent and public speeches similarly few and faint.

Why is it then that forty five years after the fact I still remember what he had said? Why do I feel that he has left an indelible imprint upon me? Why do I sense this press of gratitude and apology when I think about him, thankful because of my contact with him, and concerned that I may have failed him? Why does Razzak Sir haunt his students even though what he tangibly provided to them was apparently rather slight? I cannot answer those questions with any confidence or clarity.

It is not possible for me to offer some psycho-babble to analyze his complex personality, dredge up little known facts or documents about him, or situate him within the political/cultural forces unfolding at the time. All I can submit are some very personal impressions of the man I knew and revered, a man who could be distant, but also warm, vulnerable, and intriguing. As a student I went to his office often, as a colleague (after 1973) to his house. Did I really "know" him? I am not sure. But, I was close to him, and listened to him closely. The basis of this essay largely rests on that conceit.

I must point out, without being defensive, that the usual classroom that we were familiar with in Bangladesh was not the appropriate milieu for Razzak Sir. In South Asia, where "good teaching" is a craft that is practiced with much preparation, devotion, and recognition, and in Dhaka University in the late 1960s where great teachers were abundant and had a commanding presence, Razzak Sir suffered in comparison in the context of the conventional classroom instruction we glorified.

There is no doubt that listening to some of our iconic and charismatic professors was a pleasure and an inspiration. We used to flock to their classes, hung on their every word, and eagerly reached for the books and references they may have mentioned. There were "legendary" teachers like Professors Muzaffar Ahmed Chowdhury, S.M. Ali, and Najma Chaudhury in Political Science, Saduddin Ahmed and Badrudozza in Sociology, Ghiyasuddin Ahmed and Santosh Bhattacharya in History (both murdered in 1971), Sarwar Murshid and Jyotirmoy Guhathakurtha (also killed) in English, Anisur Rahman and Abu Mahmud in Economics, Anisuzzaman in Bangla, G.C. Dev in Philosophy (also killed), A.B.M. Habibullah in Islamic Culture and History, Kazi Motahar Hossain in Statistics (even though he had technically retired the year before we entered the University in 1967), and a host of others who would bring their own unique personalities and styles to the classroom but who would over-awe us with the sheer range of their knowledge, the organization of their material, the clarity of their ideas, and the eloquence of their presentation. There were also teachers like Drs. Hasan Zaman in Political Science, Mohar Ali in History, M.N. Huda in Economics, and others, whose political inclinations may have been questionable to us but whose teaching credentials and effectiveness were not. They were all glittering luminaries in Dhaka University's pedagogical firmament in the late 1960s. We were, indeed, fortunate to have been alive then, and being touched by so many of them.

Prof. Razzak identified with a different genre of teachers altogether. In today's parlance, he was not "the sage on the stage" but preferred to be "the guide by the side". It was not for him the rhetorical flourish, the arresting anecdote, the dramatic example, the witty riposte or the usual repertoire of practices that reduces good teaching into high performance art. He situated himself within a much older Indian intellectual convention and practice - the parampara (tradition) that binds a guru (teacher) and shisya (student) together.

Education was not something that you hawked like a vendor at a carnival, or ladled out in large dollops into empty heads. It had to come from the student, from his/her curiosity, dedication, attitude, perseverance and, beyond everything else, humility. Razzak Sir would not light a fire in your belly. But if you brought some embers to him he would gladly fan it into a blaze. (He may have said something very close to me once. But, I do not remember the exact language and, hence, would not like to quote him. Moreover his provincial Bangla is difficult to capture in English. How would one render "ami ektu foo diya dimu?" i.e., "may I blow on it a bit"?).

I cannot resist providing some examples of his "foo" that would open up a range of information and perspectives for me. I had multiple fragmentary conversations with him (unlike Sofa bhai who talked to him for hours at a time), trying desperately to please him and impress him. He was always pleased that I tried, but seldom impressed with my effort.

I remember that, around 1969 or so, while discussing the student led turbulence in our country, I had referred to Martin Luther King's famous "letter from Birmingham jail" wherein he had argued that he had no moral obligation to abide by an unjust law and therefore chose to suffer the consequences of disobeying it. Razzak Sir was very happy that I had brought this up, but with the inimitable twinkle in his eye, "kintu baba, …" ("but, my child …") he proceeded to contextualize for me the history of this philosophical position. He pointed out Thoreau's commitment to civil disobedience, and the persecution of Galileo and Socrates (all of which I knew). But, he went on to mention Khona (of Khona's bochon or "Sayings of Khona" fame - I did not even know that Khona was an actual woman who lived in history, who preferred to have her tongue cut off by the king rather than retract what she thought was the truth she had spoken), and Antigone (who died defying King Creon's order not to provide the burial ritual for her brother because she had felt that it was the right thing for her to do), and even perhaps Jesus Christ who remained unbowed even as he faced withering interrogation, brutal punishment and horrific death. What does one do when your ethical/spiritual commitments pull you in one direction, and the legal/regime requirements push you in another? This was not an altogether novel question, but Razzak Sir made me think about "the martyrs for justice and truth" in a way that was completely beyond my intellectual reach at that time.

On another occasion, in a casual discussion on communalism I had lamented how stupid and illiterate people nurture and express their hate towards others in appalling bigotry. He stopped me and pointed out that it was actually not poor and ignorant people (who, for the most part, do not care what someone else believes), but educated and intelligent people who bear the responsibility for most of these conflicts and violence. He indicated that it was the rise of the middle class under the British and the contest for jobs and power that fueled the communal divide in the country (his dissertation echoed this sentiment as well it had begun with something like, "The independence of India only meant that instead of a white bureaucracy, we would have a brown one" or words very close to that effect).

In a bold pivot on that theme, he went on to suggest that the Middle East presented a similar theater in terms of the difficulties between the Israelis and the Palestinians. He pointed out that the issue has never been between Jews and Muslims because they had lived in relative harmony throughout most of their history (and certainly their relationship did not carry the bruising scriptural and historical misunderstandings that divided the Christians and Jews). The conflict arose because of competing claims over finite resources (which leaders may exploit to further religious agendas). Today, we take much of this for granted. But, 40-45 years back, to a young undergraduate student in the late sixties, they were profound insights, and I continue to believe in them.

He is the one who first indicated to me the difference between capitalist/industrial/linear time and feudal/agricultural/circular time; suggested that Shakespeare's alleged anti-Semitism was overblown (he pointed out Shylock's famous speech from the docket, "Hath not a Jew eyes…"); introduced me to the concept of "the crisis of rising expectations" after radical changes in society (such as the independence of Bangladesh); encouraged me to read Karl Popper (anathema to those with a pretend commitment to the other Karl); and strongly advised me to learn Arabic and Persian, a suggestion that, given my secular fundamentalism , I treated with amusement if not disdain.

His last suggestion, made in 1973, demands an explanation. First, he argued that the world will change within the next two decades, the importance of the Middle Eastern countries will be dramatically enhanced, and it would be to our advantage to have the linguistic capability to navigate that world. Second, he was convinced that exploring Indian/Bangladeshi history would be incomplete without familiarity with the relevant source material in Arabic and Persian. He alerted me to the rich Akhlaque literature that existed, the debates between the adherents of wahdat al-wujud and wahdat al-shuhud, the role of the Firangi Mahal and Deoband seminaries (much before Western scholars made these names "sexy"), and historical accounts such as Siyar-ul Mutaqherin or the more didactical tracts relating to religion and practice such as Dabistan-i-Mazahib. Other names escape me. He was absolutely right of course. Unfortunately, I did not take his advice, and I rue it even today.

But if there was one position he took that appeared to be almost heretical in the context of the romantic and aesthetic fantasies of the Bangali middle class, it was his argument that Ishwarchandra Bidyasagar was more important to the Bangalis than Rabindranath Tagore. Of course Rabindranath entertained us, but it was Ishwarchandra who reformed us, and educated us. It was he who was the tireless and visionary stalwart that had struggled for a host of social transformations in the context of repressive Hindu personal law. Moreover his life style based on simplicity and sacrifice, and his inherent generosity as a human being, was more consistent with Razzak Sir's own inclinations and practices.

But, more than anything else, it was Ishwarchandra's unalloyed dedication and contribution to education in Bengal (he had advocated for, and made available, educational opportunities for non-caste Hindus and women, engaged in ambitious translation projects, over-hauled Bangla grammar, devised a crisp and direct style of writing that was more restrained and academic, participated in the development of publishing technologies that initiated the glorious period of "print capitalism" in the country without which the Bengal Renaissance would not have unfolded, and pioneered an educational system based on modern, scholarly and universal norms and practices) that endeared him so powerfully to Razzak Sir. The poet Rabindranath may have appealed to him, but it was the quintessential educationist Ishwarchandra who beckoned to him as a kindred soul.

Nothing sparked Razzak Sir's enthusiasm or provoked his interest as much as a discussion about education particularly about his life-long love Dhaka University. He knew its history and culture intimately and would often dazzle his listeners with his encyclopedic knowledge about this institution. What deliberations and distractions led to the formation of the University in 1920? What contributions did P.J. Hartog and G.H. Langley make between 1920 and 1934 as the first two Vice Chancellors of the University? How did Sir A.F. Rahman perform as the first "native" to serve in that capacity, and then Dr. R.C. Majumdar (the eminent historian) later? What were their visions, capabilities, challenges, constraints and achievements? What external pressures and internal politics did they contend with? How many brilliant teachers were they able to recruit and how many left after the Partition in 1947?

He even knew the names of almost everyone who had been conferred with the Honorary Doctor of Laws by Dhaka University, and the context in which it occurred. He noted that in the year he was inducted as a faculty member in the University (1936), the Doctorate honorees included Jagadish Chandra Bose, Jadunath Sarkar, Sarat Chandra Chattapaddhya, Sir Muhammad Iqbal and Rabindranath Tagore. I have often wondered how it would have felt to have participated in THAT convocation ceremony. In recalling some of others, he would sometimes wince (e.g., Khawja Nazimuddin in 1949, Iskander Mirza and Madame Sung Ching Ling, wife of Sun Yat Sen, in 1956, and so on). I must confess that while he would have remembered the dates, I had to look them up.

There is one aspect of Razzak Sir that many people may not have known about. This refers to his considerable skill and appetite for tadbir-baji (lobbying) in pursuing personnel issues. He would always make the discreet phone call, or quietly visit the relevant decision makers, in order to advance the case of someone that he held in affection or considered worthy. I am absolutely certain, though he never told me this (and would probably deny), that he must have been responsible in my own appointment as a lecturer the day after our M.A. results were announced. As I came out of my first class in that morning and went to the Teacher's Lounge rather than Sharif Miah's canteen for a cup of tea, he had said, in a sly and knowing fashion, "Najmar class nichen na aaijka ?" ("did you not take Najma's class today"?) referring to the fact that I was substituting for Najma Apa as she was on maternity leave. He not only knew about my appointment, he also knew what classes had been assigned to me. This was, obviously, "insider knowledge", and he must have been part of the "insider circle" that had made it possible.

It was in his pursuit of such an effort that he relayed to me a rather hilarious story. He had gone to the Secretariat to meet with the Education Secretary, a formidable ex-CSP who had been his student previously. Razzak Sir was dressed in his usual paijama-panjabi, and around his shoulders he had his shawl (which had clearly seen its better days). He told me that the office staff did not even believe that he had an appointment with the Secretary, spoke to him brusquely, and even hesitated to seat him in the waiting room. He pleaded with the peon to just tell the Secretary that he was there, and the elderly man, out of pity, complied. Upon hearing of his presence, the Secretary flew out of his room, profusely apologized to him, scolded everybody in his office, and respectfully ushered him in. Razzak Sir summed up his experience in this way "baba, always live in a way so that the orderlies in the office may not be impressed by you, but the boro sahibs inside will be". I have always remembered this pithy wisdom, and his commitment to simple living. I must also point out that I went through my entire University experience, first as student and then as lecturer, dressed exactly like him.

It was not only the boro sahibs of Bangladesh that held him in such respect and fondness. One of my most pleasant responsibilities was to escort various foreign scholars who came to visit Bangladesh to his house to meet him. I remember taking Myron Weiner and Marcus Franda (from the US), A. Dasgupta (from India), James Jupp (from Australia), and Michael Brecher (from Canada) to his house. It was doubly exciting for me not only because I could listen to the scintillating conversation, but also have delicious snacks prepared by his nieces Dipti and Supti. (Razzak Sir may have believed in simple living, but not in simple eating he was a keen gastronome). Knowing that Dick Wilson had dedicated his book titled Asia Awakes: A Continent in Transition (London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1970, later a Signet paperback published in 1971) to him, and hearing his praise from all these "foreign" academics, duly uplifted my colonized mind, and my chest would swell with pride.

In the final analysis, it was not what Razzak Sir knew, or whom he knew, that was so remarkable. It was simply who he was. It was his unfailing graciousness (I NEVER heard him being petty or hurtful towards anybody), his personal generosity in sharing his knowledge and his efforts to help others, his uncompromising integrity, his determined defiance of status-seeking efforts or careerist norms (he remained a senior lecturer till his retirement), his utter humility, his guile-less authenticity, his intuitive and rich understanding of historical forces, his devotion to education, his lively (almost polymathic) range of intellectual interests, and his sheer, simple, transcendental humanity, that made him a compelling exemplar. Of course he had his detractors, and some people, perhaps understandably, questioned his "achievements". But, personally, if I could be a fraction of what he had been, I would feel gratified.

Sofa bhai had once indicated to me his metaphor of Razzak Sir as a huge mansion, with many rooms, closed but unlocked doors, and many treasures in each of them. But, it was Kahlil Gibran who had said, "the teacher who is wise does not bid you to enter the house of his wisdom but rather leads you to the threshold of your mind", and John Trimble who pointed out "a saint is one who makes goodness attractive. A great teacher does the same for education". In this context, I have no doubts that Razzak Sir was both wise, and a great teacher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments