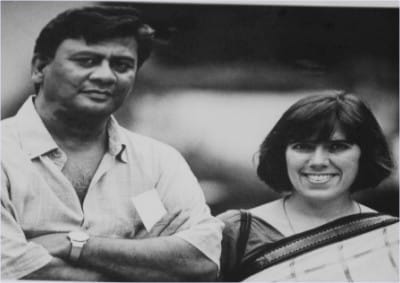

Tareque Masud: A life interrupted

Photo: STAR

Tareque Masud, filmmaker, visionary, husband, and father died in a road accident last Saturday. His tragic and senseless death, which also took the lives of Mishuk Munier and three others, has sent a ripple of stunned shock and grief though the hearts of all that knew and loved him. Tareque touched many thousands of people through his stunning, achingly tender films. As a man, he was inspirational, funny, generous, and passionate: a true force of nature.

I first met Tareque Masud through his documentary film, Muktir Gaan. Using footage taken by the American filmmaker Lear Levin during the liberation war, Muktir Gaan was a documentary that highlighted not just the horrors of war, but the intimate moments of camaraderie among a generation of freedom fighters whose political consciousness was shaped by that great event. Tareque and Catherine devoted themselves for years as they sifted through Levin's footage, working in odd jobs in New York to fund the project. After making the film, they traveled the length and breadth of Bangladesh, living out of a tent so that they could screen the film to people in the remotest corners of the country.

But it was Tareque's second film, and his feature debut, which brought him international critical acclaim. Matir Moina is a coming-of-age story set against the backdrop of our nascent nationalist movement. It is the tenderest of films, paying attention to the small details that make up a young boy's experience as he is exiled by his father to a madrasa. We witness the small moments of Anu's life -- the haircut he receives on his first day at the madrasa, his bewilderment when first asked to use a meswaaq to brush his teeth, the tentative friendship between him and his fellow student Rokon. The film allows Anu's story to unfold as revolution and war descend on Bangladesh. The film brought the Masuds the international acclaim they deserved. It was screened at the Cannes Film Festival and won the 2002 FIPRESCI prize and was Bangladesh's first official entry to the Oscars. The renowned film critic Peter Bradshaw called Matir Moina "the best film of this year -- or any other."

In the summer of 2000, I worked on the set of Matir Moina, and I witnessed Tareque and Catherine lovingly piece together every scene of the film. I had never realised how painstaking the process of filmmaking was, and I watched Tareque bhai and Catherine spend days waiting for the right sort of weather to descend before they could begin shooting. The two principal actors, Anu and Rokon, were amateurs, as were the rest of the madrasa students, and Tareque bhai was able to elicit superb performances from them with a mixture of persuasion, coaxing, and storytelling. His style was sensitive, but rigorous and unrelenting. He refused to make compromises, and the ensuing film is a testament to his perfectionism.

Tareque Masud was a deeply patriotic man. He lived simply in a rented flat in Monipuripara. People from all the different strands of his life -- friends, family (Tareque had many brothers and sisters and a vast extended family), colleagues -- gathered at their home. Their door was always open; I never visited them without bumping into various other people at the lunch table, which was always filled with bhortas, fish, and their favourite red rice from Mymensingh. He spoke passionately about the need for policy changes in the way films are produced and distributed in Bangladesh. Lately he lamented the demise of cinemas all over the country. And he traveled extensively, paying homage to his rural roots by returning again and again to screen his films and to find new locations -- it was on one of these trips that he met his tragic end.

Tareque and Catherine had the sort of relationship that most couples can only dream of. Their lives were entwined by their deep commitment to a shared set of projects, and the marriage and the work all came together for them in one symbiotic whole. I have rarely seen two people share so much and yet continue to have an abiding enthusiasm and curiosity about one another. They finished each others' sentences, they wrote scripts together, they traveled together on long road trips -- they even seemed to dream the same dreams. On the set of Matir Moina, Catherine was the practical, hands-on producer who kept Tareque Bhai grounded, while Tareque bhai stuck to his punishing schedule with a gregarious temper that kept everyone in high spirits.

Tareque bhai loved spending time at his in-laws' house in Connecticut. There he and Catherine would work on their film scripts and take a break from their manic lives in Dhaka. I met them there once, and we ate fried seafood at a roadside stall, walked through the woods at the back of the house, and at night Catherine cooked us a meal. We sat in the old colonial house of her forefathers, and I saw with admiration how much at ease they were in each others' company. It was as if, in each other, Catherine and Tareque were able to make peace with who they were, and it never mattered that they had come from vastly different places --in each other, they found home.

Tareque Bhai's death has elicited an outpouring of grief, from those that knew him intimately, to those that only knew him through his films. His death has touched a deep, raw nerve. I believe this is because he represented something to us, something great and pure. He was a hero to those of us who believe, as he did, that Bangladesh is a place of hope and beauty and potential. He embodied the spirit of a man who lived and breathed by his art, and in doing so he defied the cynicism that we all sometimes feel about our country. And, as all great artists do, he held up a mirror to each of us, to our shared past, our history, and our deepest selves. For this, and for all that he had left to give us, his death is a national tragedy.

These are the images of Tareque bhai that will forever stay in my mind: sharing a hot, freshly fried paratha with Tareque bhai and Catherine on a cold morning in Faridpur while we waited for the sun to rise over the set of Matir Moina; watching him throw his baby son into the air after returning from another of his grueling tours; his deep, bellowing laugh that filled up the entire room; his insistence on getting the perfect shot, even if it meant shooting a scene for the frustratingly umpteenth time. I will remember his commitment, his integrity, and his unflinching social vision. I will watch his films and mourn the loss of a man who had so much more to give to his family, his country, and to the world.

With love, admiration, and deep regret, I bid him farewell.

The writer is an award winning novelist, and author of "A Golden Age" and recently published "Good Muslim."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments