A musical storyteller

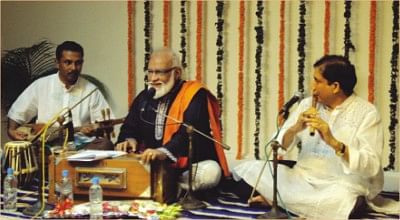

Abbasi's (centre) repertoire included songs popularised by his father, Abbasuddin.

What separates average singers from true artistes is the latter's willingness to offer themselves completely to the song they are rendering; if it makes them laugh, they do so unabashedly, and if it induces blues, eyes well up, and voices get choked. That honest passion is highly potent; when it hits the audience, they too demonstrate the same reaction.

Then there's another group of artistes -- they are the chosen few. Their craft to them is their form of worship. When singers of this kind immerse themselves in their music, the audience hears and feels the Divinity.

Mustafa Zaman Abbasi undoubtedly qualifies as both. The first time I heard him live was in 2006, at the Nazrul birth anniversary celebration. To a full house of loud, disruptive audience, Abbasi sang an Islamic song. To someone who considers himself more spiritual than religious, that song was a prayer from the innermost depths of devotion. I closed my eyes and after a while I couldn't hear the noise and chattering around me; I figured I was that much into the song. When I opened my eyes, I saw the whole auditorium was that much into the song.

Abbasi doesn't just sing, he narrates songs -- you hear the story and get the complete imagery. At the musical programme arranged by Indira Gandhi Cultural Centre, High Commission of India, Dhaka on October 29, Abbasi in his usual style engaged the audience. The occasion: Abbasi's father, legendary folk singer Abbasuddin's 109th birth anniversary. The event was held at Indira Gandhi Cultural Centre in Gulshan, Dhaka.

Indian High Commissioner to Bangladesh Rajeet Mitter and director of Indira Gandhi Cultural Centre, Ankan Banerjee, greeted Abbasi; his elder brother, former chief justice Mustafa Kamal; sister, renowned singer Ferdausi Rahman and niece, also an accomplished artiste, Dr. Nashid Kamal.

Mustafa Kamal reminisced how a young man from an affluent land-owning family in Cooch Bihar (India) became an iconic folk singer. From the urban centre Kolkata, cutting records of songs from remote corners of East Bengal was not a cakewalk either. According to Kamal, initially Abbasuddin failed to convince the studio owner to let him record bhawaiya (folk songs from North Bengal). The singer then approached Kazi Nazrul Islam to intervene. Nazrul did a composition based on a bhawaiya song Abbasuddin rendered. That song “Nodir Naam Shoi Anjona” was included in one of the records and became a hit. After that there was no looking back. Songs from North and East Bengal found their place in the Kolkata record industry. Abbasuddin, along with Nazrul, was also instrumental in initiating the Islamic Bangla songs genre.

Abbasi eased into his performance with the ever-familiar Jasimuddin composition “Agey Janley Tor Bhanga Nouka-e Chortam Na”. Among the accompanying instruments, banshi (flute) and dotara shined.

“One needn't use 12 musical instruments in folk songs. Just like we appreciate our mothers' modest, homely appearance, folk songs too sound best in a minimalist setting,” Abbasi, who is also a noted folk researcher, said.

Next the artiste rendered another Jasimuddin number, “Amar Gohin Gang-er Naiyya”. As Abbasi breathed life into the song and a bicchhedi (song of separation) after that, the essence of yearning took a tangible shape. The other side of the river, where the beloved supposedly lives, is visible, but remains elusive, inaccessible.

As he performed the bhawaiya song, “Phandey Boriya Boga Kandey Re”, a song about a pair of birds divided by a river, Abbasi said, “For our convenience, we have marked borders but artistes, musicians are like these birds. They sing of peace and universal love.”

At 74, Abbasi still effortlessly moves the audience through his sensitivity, wit and a voice that glides through bass, baritone and tenor as if it was waxed with molasses indigenous to rural Bengal. And why not? When one sings “to Tagore, Nazrul, Jalaluddin Rumi past midnight, for hours” [according to the artiste], his craft blesses him in return.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments