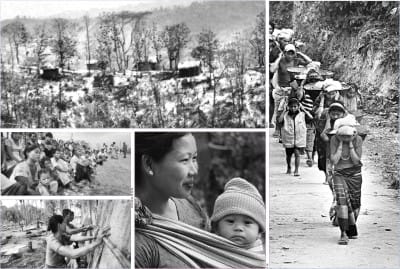

Connecting the visible dots: A post-Accord history

ACCORDING to media reports, February-March saw the worst violence against Jumma (Pahari) people in the CHT region since the 1997 Peace Accord. However, to put it in context outside a newspaper myopic timeline, the arson, killing, and rapes in Mahalchari (2006) were probably comparable in scale (10 villages attacked simultaneously).

But since that happened under a BNP government that is vocally anti-Peace Accord, it was perhaps considered "normal" (the new normal). The latest anti-Jumma violence since February 2010 has a different resonance, as it is under an AL government that came in on an election manifesto that included implementation of the 1997 Accord.

A journalist friend asked me: "Tell me, what is the real story?" What was the real story, I wondered. In 1997, I published (with Sagheer Faiz) a History of the CHT Conflict (Daily Star, Nov 26, 1997), during the week of the Accord negotiations. I had not visualised I would have to return to that history, thirteen years later. But we meet here again, after a decade of missed opportunities in Chittagong Hill Tracts.

1997

The 1997 Peace Accord is signed between AL government and the Shanti Bahini guerilla army. The Bahini lays down arms and demobilises its soldiers. The Accord promises many things, including withdrawal of army camps, rehabilitation of Jumma (Pahari) who are internally displaced and external refugees during the war, resolution of land and other disputes between Jumma inhabitants and Bengali settlers brought in during Zia and Ershad government, etc.

The nucleus of the Shanti Bahini's political wing becomes the political party PCJSS (Parbatya Chattagram Jana Sanghati Samiti). Part of the Jumma leadership are dissatisfied with the 1997 Accord, particularly the lack of constitutional recognition to them as Adivasis. These groups form another political party, UPDF (United People's Democratic Front). Over the years, rivalry develops between UPDF and PCJSS, which is also aggravated by Bengali political forces that use this tension to delay implementing the Accord.

In recent years, UPDF has shifted its opposition to the Accord -- they now state that although the Accord is "flawed," they are ready to work within its framework. But as late as 2010, media outlets and government spokespeople continue to incorrectly describe UPDF as "anti-Accord," a characterisation the UPDF contests.

1998-2001

BNP announces "long march" from Dhaka to Hill Tracts opposing the 1997 Accord and threatening to bring down AL. It is a calculated overture towards Bengali factions and state forces that are unhappy with the Accord. Jamaat joins the campaign. Some small steps are taken as per the Accord (Regional Council and Land Commission set up, Land Commission law passed, Hill District Councils receive 19 of 36 promised functionalities). But on balance, AL does not manage to implement the Accord, leaving most of the sensitive issues untouched. In addition, Land Commission Law is severely flawed, and Jumma spokespeople ask for 19 amendments.

2002-2005

AL is defeated at elections. BNP enters government in a coalition with Jamaat, with the latter taking control of two powerful ministries: Social Affairs (which controls NGOs) and Industries. BNP strategists identify religious and ethnic minority populations as pro-AL. In a calculated scare campaign, Hindu populations are targeted for revenge attacks by BNP cadres.

In CHT, BNP's strategy is to continue and accelerate the policy of 1970s and 1980s, displacing ethnic minority Jumma population with Bengali Settlers. In addition to land grabbing, Bengali Settlers systematically occupy all levels of administration. Jumma activists allege that the administration is engaged in "Islamicisation" and "Bengalicisation" of regional governance.

Although the Accord remains largely unimplemented, the fact of its signing allows entrance of NGOs into the region. Although their programs are modeled under post-conflict rebuilding programs (similar to regions such as East Timor), they are not allowed to work in "sensitive" areas. NGOs are limited to working in education, agriculture, etc. Even with this limited scope, their work does begin to bring some economic development into Jumma communities. NGO employment also increases the creation of a professional, white collar segment within the Jumma population.

2006-2008

Pre-election confrontation between BNP and AL. A state of emergency is declared and an army-supported caretaker government takes over. There is widespread arrest of politicians and political activists from both parties. CHT region faces disproportionate amount of mass arrests. Legal aid groups file numerous cases to free arrested Jumma, and prevent their torture.

Bengali settlers continue tactics of arson and attacks to displace Jumma. In one such case, groups of Jumma houses are burnt down in Sajek. There is sustained protest from civil society. In a pattern that is repeated, people who speak to visiting investigators are later persecuted by Settlers and local administration

In 2008, the country begins negotiations towards elections and a return to civilian governance. The nation's mobile phone companies are allowed to operate in CHT for the first time, changing a decade-long government ban for "security reasons."

In a stunning decision, the Election Commission announces that neither of the two political parties representing Jumma -- PCJSS and UPDF -- will be allowed to compete in the elections, because they "only represent a region" and are not "national parties." Unable to field candidates, UPDF and PCJSS try to field independent candidates, but are prevented from campaigning properly. AL candidates win in all three districts.

2009-2010

AL enters office, buoyed by an election manifesto that includes, among other things, a promise to fully implement the 1997 Accord and to uphold the rights of ethnic minorities. There is considerable hope among CHT Jumma for the long delayed Accord implementation. However, two months later, the massacre at the BDR headquarters is a major destabilising incident. Behind the scenes, the BNP actively foments propaganda that tries to blame the AL for mishandling hostage negotiations.

CHT Accord takes a back seat until winter, when its 12th anniversary arrives with fanfare. Unprecedented attention is given to the issue from government, NGOs, media, and civil society. Pressure continues to build on the government to announce a timetable for implementation.

At the same time, powerful Bengali economic groups which have benefited by grabbing huge tracts of land from Jumma in CHT, and profited from illegal timber felling and cross-border smuggling, group together under anti-Accord banners.

Bengali settler groups like Shama Odhikar, formed during BNP tenure and patronised by state forces, are well-funded and lead agitations and scare campaigns against the Jumma.

These groups begin various efforts to destabilise the trajectory towards Accord implementation. No government action is taken against them, despite openly communal and racially motivated demonstrations, posters, and other acts.

AL government removes 35 army camps from the region, in a symbolic gesture towards fulfilling the 1997 Accord. Although this represents a minuscule portion of total army camps in the region (one newspaper estimates it be "around 10 percent"), BNP responds vociferously, demanding that such withdrawals be halted.

BNP high command, decimated by their landslide defeat in the 2008 elections, starts to regroup on a platform of "wedge" issues. Opposition to the 1997 Accord is seen as one such issue, and there are efforts to again bring up allegations of "separatism", even though the Accord has no such provisions. BNP and Jamaat aligned lawyers continue legal cases in the High Court (one dating as far back as 2000), attempting to declare the 1997 Peace Accord "unconstitutional." In the final ruling, the court upholds the Accord, but declares Chittagong Hill Tracts Regional Council Act illegal.

Since 2002, one core platform of Bengali groups in CHT has been to dispute the description of the Jumma as "indigenous" or "Adivasi." This term has potential legal rights ramifications, especially vis-à-vis international human rights treaties. During the BNP government, a minister declared that "Bangladesh has no indigenous people." AL Foreign Minister Dr Dipu Moni appears to reflect the earlier BNP minister's statement, when she says: "Bangladesh does not have any indigenous population. Bangladesh rather has several ethnic minorities and tribal population." In 2010, the CHT Affairs Ministry shocks Jumma activists by issuing a mysterious memo ordering that the Jumma not be referred to as "Adivasi" or "indigenous" in any government documents.

Various government agencies, in conjunction with UNDP, plan a national convention in spring 2010, to discuss implementation of 1997 Accord. Government is asked repeatedly by civil society groups to announce a timetable for implementation. The government response, particularly from relevant ministers, is lukewarm and vacillating, and no timetable is announced. Meanwhile land grabbing continues in CHT, coupled with garish hyper-development linked to tourism development bodies -- all managed and run by Bengalis.

Jumma communities continue a boycott of local markets, in protest against land grabbing by Bengalis. Bengali settlers carry out fresh attacks on Jumma in Sajek, which was also site of 2008 violence. The situation escalates when the army fires on Jumma protesters. The official death toll is two Jumma dead, but there are claims that many more dead Jumma's bodies have "disappeared."

A cascading wave of arson and physical attacks spread into other areas in Khagrachari and destroys many Jumma homes. A Bengali settler, part of a mob that attacked a Marma village, is killed by villagers who were resisting the attack. There is a partial media blackout as curfew is declared and journalists are not allowed to enter the area. News comes out through mobile phone calls and text messages, but mobile networks also go down frequently during the violence.

BNP comes out with statements that the violence proves army camps cannot be withdrawn from CHT. Jumma activists, including leaders of UPDF and JSS, argue in public media that the presence of the army does not prevent violence -- in fact Bengali settlers feel emboldened by their presence to carry out anti-Jumma attacks.

Bengali activists also continue to question role of administration and security forces, as violence continues even in their direct physical presence. In several areas, BNP- and AL-aligned administration members allegedly join forces to covertly support Bengali settlers.

Bhumitra Chakma publishes "Structural Roots of Violence in CHT" (EPW, 20/03/2010), where he identifies the root cause of destabilisation: "From the late 1970s, the Bangladeshi government has consistently pursued a policy of 'change the demography' in CHT. The only objective of this policy appears to be to outnumber the indigenous people in their own land."

Raja Devasish Roy says in a wide-ranging interview (Daily Star, April 2): "We cannot forget the ethnic and religious affiliations behind the uniforms. Since all members of the army and police in the region are Bangalis, and there is Pahari-Bangali tension, there is a big risk of bias. What is needed is an ethnically mixed police force with special training, if necessary, to handle law and order problems."

Naeem Mohaiemen has written on religious and ethnic minorities for Ain o Salish Kendro Annual reports and Drishtipat. He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments