Tagore --- spinning poems and songs

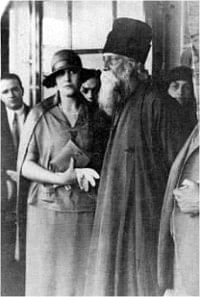

Tagore and Victoria Ocampo in 1930

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) remains a superman for us, even at this distance in time. He was the same to his contemporaries, though not until he reached the years when he would be recognised as a poet at home and abroad, and when this growing fame would be crowned with the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature. It is interesting to see, though, how he evolved from a common man, from an uncle or father, into a literary giant in the eyes of his close relatives and friends.

I have recently had the chance to come by a rare volume on Tagore, entitled Rabindranath Tagore: Centenary Volume: 1861-1961, published by Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, in 1961, In the second section of the book, Personal Memories, are five essays where the writers reminisce on Tagore. Given the diverse impressions of Tagore that these essays provide, a composite portrait of Tagore can be drawn from them.

The articles in my consideration are the following: Uncle Rabindranath by Indira Devi Chaudhurani; Personal Memories by Leonard Elmhirst; Tagore on the Banks of the River Plate by Victoria Ocampo; Father as I Knew Him by Rathindranath Tagore; and Recollections of Tagore by Guiceppe Tucci.

Indira Devi Chaudhurani was the eldest daughter of Tagore's second brother, Satyandranth Tagore (incidentally India's first Indian ICS). In her recollections in very lucid English, what transpires is that Tagore was very much the adorable uncle of the family, was always capable of inspiring children, arousing their creative interests about life, and himself a great entertainer in mimicking and producing histrionic performances.

Rabi Kaka had an excellent physical constitution (also noted by Rathindranath in his essay --- that Tagore was a very good swimmer), though a little darker in comparison with the generally fair complexion of the members of the Tagore family, and would wear kurta and pyjama at home, and dhoti and chadar when going out. As a young man, the poet would wear on his head the pirali pagri, or the Iranian topi or the Turkish fez. While wearing trousers Tagore would wear English shoes, and slippers with dhoti.

Much to the delight of the children in the family Rabi Kaka used to compose songs in Bengali, fitting into them tunes from other parts of India that the children had heard. Though Tagore was never given to playing any instrument, at his request Indira and her brother Surendranath would often play the piano and the esraj to the accompaniment of the newly composed songs Tagore had made in the mode of European music, for which the Tagore family had a natural fascination. This probably explains the virtuosity of Tagore's songs in which the dazzling variant of the tunes has a delectable sonority.

Tagore also wrote the dramas Visarjan, Raja o Rani and Valmiki-Pratibha in his early life and produced them on the stage in the Jorasanko house. In one of the plays, Indira remembers, there was staged a duel with tin swords and "appropriate gestures and songs" between Rabindranath and Jyotirindranath, another brother.

The essay has a rueful recollection, however, of her aunt Kadamberi Devi, who, according to Indira, provided the much-needed affection to Tagore which he had been missing at the loss of his mother in his early life.

While Indira's essay mainly describes Tagore's artistic propensities, Rathindranath's reflections on his father focus on a reformative Tagore, much concentrated on the development of the villages around Shelaidah and Potisar. This article can be read in tandem with the essay written by Leonard Elmhirst, where Tagore is portrayed very touchingly as a man who failed in his reformative bid in the face of political action taken up by Mahatma Gandhi.

Tagore sent Rathindranath, Santosh Majumder and his youngest son-in-law, Nagen Ganguli (Mira's husband), to earn American degrees on agriculture in his conviction that what India needed was scientific agriculture. That also became the motto of the Swadeshi Samaj, a movement that Tagore would briefly lead as his only active political programme in life. This programme was based on the idea of bringing comprehensive development to the village, albeit by keeping the zamindar at the helm of things. Rathindranath states that in the Pargana of Kaligram there were 1,50,000 bighas (roughly 70 square miles of land) with sixty to seventy thousand people living in 125 villages. Tagore wanted to make these villages self-governing by introducing a system through which a central administrative body called the Hitaishi Sabha would look after all affairs of the villages, with the Pradhana and Panch-Pradhana at the head.

In Rathindranath's essay we do not get to know why Tagore failed in his philanthropic objectives, but Elmherst's essay provides definite clues to the reasons why Tagore failed.

These two great men of their time, Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranth Tagore, had the same vision --- the emergence of India as an independent country. But their paths diverged in methods. Tagore thought, as is also profusely reported by Ocampo in her essay, that struggling against the British in order to achieve political sovereignty was less important than placing India on economic self-governance. Tagore had an innate resentment of the idea of nationalism and so wanted Indians first to develop scientifically. He understood that the West had a better technological edge by which it dominated other regions of the world. Instead of abandoning the technological West, he wanted some sort of accommodation for which reason he could not totally support Gandhi's non-cooperation movement. As far as his political goal was concerned, he thought improving one single village could be the starting point.

Elmherst quotes Tagore on the conversation that took place between Gandhi and the poet. Gandhiji told Gurudev that his Swaraj movement was the natural child of Tagore's Swadeshi movement, so Tagore should join it to strengthen his hand. In reply, Tagore said to Mahatmaji that the Indians were by nature very emotional, and if in the name of nationalism their emotions were triggered the wrong way, then Gandhiji's non-violent programmes would not remain without bloodshed. Tagore, as Elmherst says, could not digest the idea of Indians of burning the foreign cloth imported by Indian businessmen. His view was that ethically it was not right; before the nationalists burnt the cloth they should have bought it.

Gandhiji then said (quoted by Elmherst as said to him by Tagore), "Well, Gurudev, if you can do nothing else for me you can at least put these young impractical bhadrolog, with their Calcutta degrees, to shame by getting them all to sit down and spin. You can lead the whole nation and spin yourself."

In reply, Tagore said, "Poems I can spin, songs I can spin, but what mess I would make, Gandhiji, of your precious cotton!"

Elmherst's essay reveals the fact that Tagore failed in his agrarian policies at Surul and in Potisar because of stiff opposition from the followers of Gandhi's nationalistic movement.

The essay also throws significant light on Tagore's awareness of the progress China was making in agriculture. Perceiving the co-existence of the poetic and social selves in Tagore, Elmherst writes, "The introspective artistic-mystic poet in Tagore had to try and make peace with the crusading philosopher-humanist," and fittingly ends his essay by quoting a passage from a letter of Tagore, written to him on 2 June 1940, that again condemns nationalism: "History is waiting long for a perfect renewal of spirit through the elimination of short-sighted nationalism."

Victoria Ocampo, in her essay, Tagore on the Banks of the River Plate, mentions her deep adoration for these two great Indians. Ocampo, who had already written essays on both of them in La Nacion, Argentina's reputed newspaper, explains how they both affected her: "The debt that I, a Westerner and a South American, owe to men like Gandhiji and Gurudev is like the restitution of a treasure I had inherited without being aware of it."

But it is Tagore that she writes about, and how wonderfully does she do it!

Tagore was to go to Peru in September 1924. Elmherst was with him, but as the ship anchored at Buenos Aires, Tagore developed a terrible cold and doctors advised him complete rest and an avoidance of travel and company. The bungalow at San Isidro on the bank of the River Plate was fixed by Ocampo to provide Tagore the necessary retreat. Tagore was recuperating and composing the verses, to be later on compiled in the volume called Purabi.

The relationship, however, got complicated, as Ocampo, out of deep respect for Tagore and also over great concern for his health, would not visit Tagore as often as she could, and Tagore, in his turn, would interpret that as her avoidance of him: "the young woman who took her role of a convalescent's nurse so seriously that she ran the risk of annoying him." Tagore also thought that perhaps Ocampo's little knowledge of English was in the way of her desire to talk to him. She writes about one such occasion when the misunderstanding would speak for itself: "In the afternoon, usually at tea time, having decided to be once and for all very bold, I used to knock timidly at his dooras if I came from the outside world: 'Is that you, Vijaya? You've had a busy day!' he would say. Indeed very busy, thought I, despising myself for my speechlessness. Waiting for the right time to see you."

Naturally, Tagore's hurt tone tells us that Ocampo's shyness made him think otherwise.

However, the river view was exceptionally beautiful, and Tagore's favourite time of the day was dawn breaking on the banks of the river. So he would sit in his armchair--a gift from Ocampo, which Tagore would use until his last days--in the morning and enjoy the sunrise as he did many years ago in his young age from their Jorasanko house, and was prompted to write the famous poem, "Nirjharer Swapnobhango" (The Breaking of the Dream of the Stream).

The river view in Ocampo's language may be quoted just to feel the immensity of the beauty it contained: "The river, true interpreter of our sky, was giving in its own way and in its own language the image of what we saw above. Tagore and I looked from the balcony of his room on the landscape where everything, the sky, the river, and the earth, decked in 'embroidered clothes', the willows weeping more tenderly with their new curly leaves, was bathed in the diffused illumination of an abortive storm."

Ocampo's feelings for Tagore are difficult to characterise because they are a mixture of sublime love and affection, deep regards and immense care at the same time. One day she found Tagore busily scribbling poems. She wanted to know what they were about. Tagore instantly translated them verbally, and Ocampo felt that they were the most sublime lines she had ever heard. The following morning, at breakfast, however, Tagore showed her the written translation of the poems. She was horrified, and asked him why he had not retained the first translation he had done extempore the previous day. Tagore said he thought western readers would not appreciate that. Then Ocampo used the image of the gloves to explain to Tagore that she felt the written translation now came to her like poetry in gloves, blunt to the sense of touch.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments