A MASTERPIECE REMASTERED

If you're a Bengali or an art house film buff of any nationality, you've most likely heard of Satyajit Ray, one of India's finest filmmakers, whose debut in 1955 as a screenwriter and director was Pather Panchali (the first in a trilogy) set in early 1900s rural Bengal, following the life of a watchful little boy called Apu. This critically acclaimed period piece is especially astonishing considering that Ray's cinematographer, Subrata Mitra was only 21 years old, and neither he nor Ray had ever shot a film before they started this movie.

Sentiments about the trilogy range from labeling it dramatic poverty porn to the highest of art. There is no shortage of praise or prizes for the films world-wide, and the 1960 American release lasted eight rapturous months. No matter what you think of the trilogy, there's no denying their silver lambent beauty, and their assured spacious glacial pace.

Ravi Shankar lends his myriad marvelous talents to the scores of all three films, and for the first two he improvised the music over the course of a single viewing. Mitra the cinematographer, who was also a very talented sitar player, filled in when Shankar couldn't be there. It's no wonder then that even though the 1955 premiere at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) was without subtitles, people still left the theatre weeping.

None of this is new. What is new is the restoration story of the Apu trilogy negatives and the re-release of the trilogy this past spring in America. In 1992, just before he died, Ray received an honorary lifetime achievement Oscar at the Academy Awards. The producers who put together a reel of his work were shocked by the poor condition of the existing prints, and thus a project was born to restore them.

It may very well be that those who were lucky enough to watch the original release in Indian theatres and then worldwide in the 50s and 60s were the first and the last to see what shining sharp beauty Ray and Mitra actually wrought. In the decades to come, reprints and videos have been marred by sludgy visuals and muffled sound. There has never been a high quality VHS or DVD release of the trilogy.

As writer and filmmaker Ruchir Joshi recounts in his ode to the forgotten master technicians and less celebrated but no less talented directors, he watched the trailer for the restoration of the Apu trilogy, and "the stories of Subrata Mitra's volcanic frustration about duplicate prints and dim projection lamps all come into sharp focus. 'None of you have actually seen what we really made!' is one quote from Subratababu repeated by many who interacted with him in his last years."

In 1993, the original negatives of the trilogy and several of Ray's other films were sent to America to be restored as part of a project to keep his work alive through the ages. A stopover in London at Henderson's Film Laboratories proved disastrous. A fire at the lab spread to the film vaults, destroying more than two dozen original negatives of British classics, and burning several Ray films, including the originals of the trilogy.

The fragments, ashes, and film canisters that could be identified as belonging to Ray's films were sent to the Academy Film Archive, but they were unprintable - the damage was too great. Still, the AFA held on to the pieces in its vaults. Twenty years later, in 2013, the Criterion Collection along with L'Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, a top restoration facility in Italy, began six months of painstaking manual restoration work using new technology and old school labour. It would take hundreds of highly skilled technicians 1000 hours, a task which even included rebuilding the sprocket holes on the sides of the film and removing melted tape and glue.

Frame by frame, the technicians were able to restore up to 40% of Pather Panchali and over 60% of Aparajito, the second in the trilogy, from the original negatives. The rest of the two films, and the entire third film, Apu Sansar, had to be restored from fine-grain masters and duplicate negatives. If befores and afters fascinate you as much as they do me, take a look at the restoration trailer online – it's a magical thing.

On May 4, 2015, sixty years almost to the day, Pather Panchali re-released at the MoMa in New York City, with dozens of film luminaries in attendance, many of whom had seen the original premiere or later screenings in the 60s. The audience included Ken Burns, Wes Anderson, Joel Coen, Noah Baumbach, Jim Jarmusch, Laurie Anderson, Shampa Banerjee - the actress who played Apu's sister, and Ray's son - Sandip Ray.

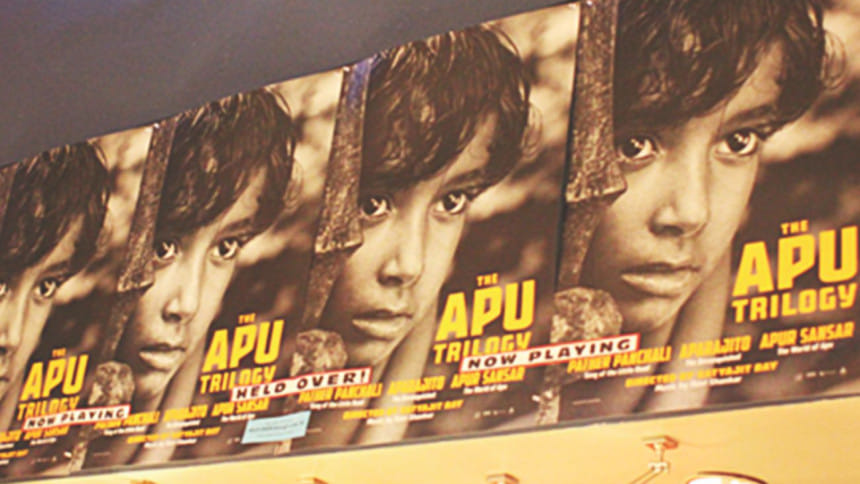

After that first night at the MoMa, the Film Forum, an independent theatre in the West Village took on the rest of the screenings. I went to the Film Forum days after the initial release, and despite the fact that it was a Monday night, the line stretched down the block outside the theatre, an eager whispering crowd.

Every other time I've gone back, either to see the other two films, or just passing by, there has been an excited queue. In fact, interest in the films has been so great that the initial two-week run of the films has been extended into mid June. The films will continue to show throughout the summer in over thirty cities nationwide.

Many of my friends who've gone to see the films in the last few weeks are new to Satyajit Ray's work, or any independent art house film from South Asia. Writer and oral historian Svetlana Kitto is deeply interested in origins and process. She had never heard of the films before now, and she found them a revelation: "shockingly beautiful, with an artistry of black and white that seemed almost richer than color. It was an accessible, modern, intimate coming of age story which beautifully, richly captured the interiority of childhood." Seeing the films reminded of watching her first Italian neorealist film and thinking, "This is how a movie can be. So much depth."

I cannot claim any more context than Svetlana, other than knowing Ray's name and fame. As a failed Bengali, the only other Ray film I've seen was a short on YouTube earlier this year. I've only seen the occasional Bollywood film, and of course cannot compare the Apu trilogy in any way to the schmaltz and gloss of those movies. It was more like watching a meditation, one in which the filmmaker has utter control of the pace. You will watch dragonflies on the water for five minutes if Ray and Mitra want you to, and it will stun you into silence. I had the sensation of having to put aside my headlong American narrative self. Svetlana put it more elegantly. She said she had the feeling she was being taken care of, that she could just sit back and let it all wash over her.

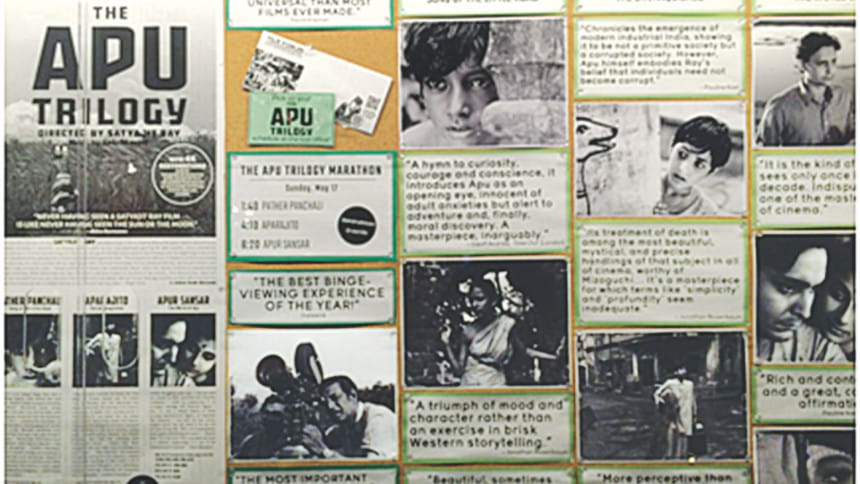

It was true that the audience sat in the theatre for over two hours that first night watching Pather Panchali in pin drop silence, a rapt quiet occasionally broken by a sigh or chuckle. Afterwards, the lobby of the theatre filled up, with audience members crowding the bulletin boards which were plastered with interviews and articles and praise for the Apu films.

Svetlana told me that the Apu movies made her think about the history of that part of the world: "It was an invitation to learn more." And as my more savvy cultured South Asian friends have been telling me for years, it is an invitation to me as well. Ritwik Ghatak, Aparna Sen, and Mrinal Sen are three of many critically acclaimed filmmakers to come out of the Subcontinent. There are many many more.

If you're in the United States, go watch the Apu trilogy on the big screen this summer. Leave your watch behind. Take your wonder.

Abeer Hoque is a Nigerian born Bangladeshi American writer and photographer. See more at olivewitch.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments