IF YOU WANT TO KNOW WHAT LOVE IS

At around 8:30, a sunny and cool November morning is just beginning in Khagan, Savar, and cars are pulling into the parking lot of the BRAC-CDM. At the reception, people—more than 400 of them—are waiting patiently to register for the 2014 ASCoN Annual Conference. Some of them have travelled from the US and Europe to be here, while others from various parts of the country. There is great energy in the air. My eyes look for someone whom I have only heard about and am eager to meet.

There are only two kinds of people here—those who have suffered spinal cord injury and those who work to treat or cure them. The conference is hosted by the Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed (CRP) and aims to share the latest developments in spinal injury management worldwide.

Md Foysal Rahman, an assistant teacher at Jhalakati Government High School, has the injury. In 1987, while a student of class seven, he was hit by a train when his bicycle got stuck in a rail crossing. “I underwent treatment in Singapore and India. Then I came to CRP. With the encouragement of Valerie, the founder of CRP, I have earned a Masters from Dhaka University. I have also completed B Ed and M Ed.” His injury left him paralysed from the waist down.

That's one thing about spinal cord injury — everything about it plays out in absolutes. They are instantaneous, utterly disabling and horribly permanent. One moment you are the strongest person in the world, the next moment you find yourself in a wheelchair.

On January 18, 2012, Tania Sultana Munni, a school teacher was riding an auto rickshaw and all of a sudden her shawl got caught in the wheel. Her neck was broken immediately. “After receiving treatment at another hospital, I came to CRP. I received treatment and counselling for 6 months here. The games and cultural activities helped me a great deal. I am almost well except a little weak in my hands. Valerie (Taylor) gave me a job as an office assistant at CRP.”

Like Foysal and Tania, most of the patients come to CRP after being released from other hospitals. “CRP is the only organisation for the management of the injury and rehabilitation of patients,” Dr Mostafa Kamal says, “We take an interdisciplinary approach providing physiotherapy, occupational therapy, counseling and vocational training.” Dr Kamal is the Head of Medical Services at CRP.

Anwar Hossain is a beneficiary of that. In 1988, when he went to a well-reputed hospital with a chest pain, the doctor told him he had a tumour in his back and needed surgery. “He mistakenly cut two nerves. I was paralysed from the chest down immediately. They referred me to CRP. In addition to giving me physiotherapy and counselling, they showed me videos and brought role models from here and abroad to boost my confidence. They encouraged me to work and gave me a type writer.” Today he is a project manager of CRP and also the secretary of SCIDAB (Spinal Cord Injuries Development Association Bangladesh).

One of the main challenges after spinal cord injury is to regain independence. “Physiotherapy helps improve independence in daily activities,” Professor Tomasz Tasiemski PhD says. “A person first must be independent in order to continue education, work, and look after the family and so on. Participating in sports is also very important for the physical and psychological development of the patients.” Dr Tomasz, Head of department of Sports for People with Disabilities has travelled from his native Poland to be here. During his first week in Bangladesh, he trained the trainers at CRP.

It's after lunch and we are at CRP—a 15-minute drive from the conference—to see the place that has turned so many lives around. What we see as soon as we enter the premise takes us by surprise: A tri-nation tournament! “In power lifting, Hafizur Rahman has just won the first prize lifting 102 kgs (225 pounds),” Pappu Lal Modak, sports trainer at CRP, eagerly says. “Our basketball team has beaten India 76-5. Mehedi Hasan Rizvi from Bangladesh has reached the semi-final in table tennis.”

At the basketball court outside a group of players practices while spectators cheer them on. Pintu, a 16-year-old who broke his backbone after falling from a tree whizzes past me on his wheelchair, singing a popular film song. When was the last time I sang a song aloud?

The overall picture of the country, however, is very different with few exceptions. For people like Pintu, the built environment is full of uncertainties and anxieties. None of the public spaces is designed with their needs in mind. Be it bus stops, railway stations, shopping complexes, public buildings or toilets, they feel short-changed by poor planning and sheer neglect.

The Bangladesh Army is one of those exceptions. In 2012, Kaniz Fatima, now a Second Lieutenant in the Bangladesh Army, met with an accident when she was about to get commissioned. “It's not easy to lead this type of life. Things are totally changed. No one will perceive what I am feeling….from a very fast, speedy life …now it's totally still. That was more shocking when I lost my father after my accident. He couldn't bear my condition.”

The Army offered her full support. “There is no example in any other army in the world that when a trainee officer received this type of injury he or she was retained in his or her job,” Second Lieutenant Kaniz says. “All my seniors, course mates, my UNIT CO (Commanding Officer), 2IC (Second-in-Command), ADJUTANT are very supportive of me, and my commission has become possible because of the CAS (Chief of Army Staff), the present Commandant of BMA (Bangladesh Military Academy) and my Term Commanders.”

Second lieutenant Kaniz also works as an official translator for Queens University, Canada, all the while remaining paralysed from C4-C5 level. “When the accident took place, from Chittagong, I was taken to DHAKA CMH by a helicopter. Then the Army sent me to Bangkok. After coming back I received treatment at CRP for six months. I think CRP is the best for the management of spinal cord injury.”

At most workplaces accessibility remains a major challenge. Anwar Hossain, the project manager of CRP says, “We should give these people a chance at education and employment. In 2013, the 'Rights of the Persons with Disabilities and their Protection Bill' was passed in the parliament. We need a national centre for SCI.”

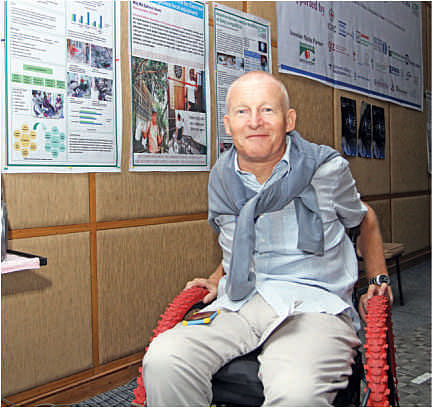

David Constantine, co-founder of Motivation says that making laws is fine but not enough to ensure equal rights. “The implementation has to be fought for just like the civil rights movement in the US.” In 1982, he was a 21-year-old on a break from college in Fraser Island in Australia. While diving into the ocean, he hit his head and broke his neck at C4-5 level.

“In 1989 I came to visit CRP with two of my colleagues, Richard Frost and Simon Gue. Simon and I designed a wheelchair while studying for a Masters in Industrial Design at the Royal College of Art in London. After meeting Valerie and seeing how CRP works, we went back to the UK and founded Motivation.” Today Motivation (www.motivation.org.uk) is internationally recognised as a leader in the design, production and distribution of high-quality, low-cost wheel chairs, trikes and supportive seating in developing countries. “The wheelchairs you see here were designed by me,” David says politely.

The name that keeps appearing in every conversation is Valerie Taylor, the founder of CRP. Where is she? Why isn't she in the front taking pictures as is the norm? Then I spot her in a corner talking quietly to a lanky gentleman. Someone tells me that's Jon Moussally, MD from the US and founder of traumalink. Dr Jon's organisation trains volunteers and local communities in basic trauma first aid so that they are able to respond to victims of traffic injuries and treat them at the crash scene. Later he says to me, “Among the things we are teaching is proper handling and transportation of patients so we can prevent unnecessary spinal cord injuries. A lot of people die or suffer life changing injuries simply because they are not getting simple care.”

Photo: Prabir Das

Each person I meet is here for a reason. They care about their fellow suffering humans. That's the highest form love can take. Dr Jon lost his father in a car crash in the US. He felt a strong sense of duty to help when he visited Bangladesh the first time. Then there is Carolyn Scott who is the president of Friends of CRP-Canada Society, a major fundraiser for CRP. She has visited CRP every year since she first visited the organisation during her stay in Bangladesh while her husband was the Canadian High commissioner here (1993-96). “I think I am the luckiest person to have met Valerie,” she says with a smile. Foysal Rahman, the paralysed High School teacher started his own organisation Protibandhi Unnayan Shngstha in Jhalakati and has helped about 2500 people like him. In 2013, he received a national award.

The moment has arrived. Dr Jon has just finished talking to Valerie. She firmly shakes my hand and softly says, “Thank you so much for finding the time to come here and support us.”

I am a little confused and totally overwhelmed. First of all, it's my job. Second, I haven't actually met anyone like her before—someone who has sacrificed her entire life to serve some of the most neglected people in the world. Her kind eyes remind me of Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa whom I had an opportunity to listen to when he delivered the commencement speech in a university in Oklahoma, US in the early 2000s. I know when I am in presence of greatness.

I ask her the inevitable question – why does she do all this? “If we send these people home after giving them the initial treatment, what are they going to do with their lives? Without vocational training and a chance of a job, they will be left alone in backrooms of their homes and watch life slip by.”

Now I know what Foysal Rahman meant when he said, “Valerie took care of me like a mother.” Who else but a mother loves this way?

“People like Foysal and Munni and David and everyone else here give me so much hope for the future,” she says. “Physically, they have so much going against them. But they have a lot to teach us all, not allowing their disability to interfere with their lives. So it is up to us the able bodied members of the community to open the door to them.”

***

The Light That Shines in the Darkness

Valerie Ann Taylor

Founder & Coordinator of CRP

A fellow of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (FCSP), Valerie Ann Taylor first came to Bangladesh with the Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) in 1969 to work as a physiotherapist in the Christian Hospital, Chandraghona in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Her stay was interrupted by the War of Independence in 1971. She came back two months before the independence of Bangladesh.

In 1973 Valerie returned to England to raise funds to establish a rehabilitation centre for paralysed people in Bangladesh. She stayed in England for two years before returning in 1975. It took another four years before CRP was able to admit its first patients in 1979. CRP found a permanent home in Savar in 1990 where the head office is situated.

Valerie's achievements have been recognised with numerous accolades at home and abroad. She received the OBE (Order of the British Empire) in 1995 from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, the Arthur Eyre Brook Gold Medal in 1996 and the Bangladesh Independence Award in 2004. She has also received several other awards among them Mahatma Gandhi Peace Award (2009), Lifetime Achievement Award (2009) by Hope Foundation for Women & Children of Bangladesh (USA), Princess Diana Gold Medal (2007), National Social Service Award (2000) by the Ministry of Social Welfare, and Anannya Top Ten Award (2000).

In 1998 she was granted Bangladeshi citizenship.

Valerie has been legal guardian to two Bangladeshi girls for several years. She lives near CRP, Savar with her younger adopted daughter, Poppy while Joyti, the eldest, a computer operator at CRP, was married in 2007. Valerie Taylor was born on the February 8, 1944, in Bromley, Kent, UK to parents Marie and William Taylor.

Photos: Prabir Das

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments