Discovering a Cold Climate Bengal

Confident concrete pillar, gleaming glass, reflection, angle and contemplative curve: seemingly simple, skyscrapers are, at their best, towers of thought. Modern design conceals little, so it seems –neither shy to be straightforward nor backward in coming forward.

How the light will play, the engineering dimensions and even the impact of shadow through the day will have been considered. Simplicity is not simplicity in the end.

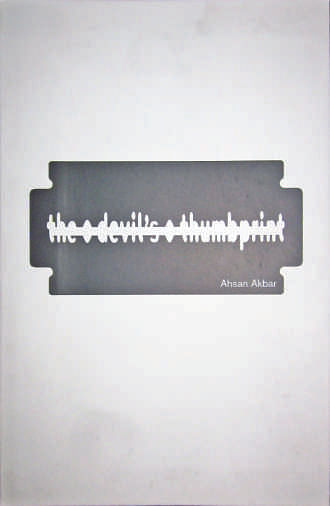

Poet Ahsan Akbar in his first collection, “The Devil's Thumbprint” published by Bengal Lights Books in 2013 has likewise pursued architecture of the modern kind. The collection was criticised on first submission, with one potential Bangladeshi publisher claiming Akbar's work was “too permissive and explicit.” It's true that some of the poems concerning the themes of attraction are not for the prudish.

But Akbar took the criticism as encouragement. He refused to consider the suggested edits and withdrew the manuscript. True to what he wanted – honesty and candour – his manuscript found its way...

It's not surprising it wasn't readily recognised. The deltaic tradition is substantially different. Whether it is the intricate beauty of Tagore, the labyrinth layers of Das or the zeal of the rebel poet – Akbar's work does not seem to draw from the same well. But the expectation of decorative adornment familiar to the renaissance building is unlikely to be fulfilled by a modern high rise. There's a need to look for something else.

In what is perhaps his most interesting poem, “Tree Without Roots”, which documents an impression of Dhaka by an outsider who really should be an insider, there is the confession that “Your soul was empty / Of the rustic Bauls...” and “Nazrul could not invoke / A blood rush...” There is an element of regret, of the Dhaka that “frightened”, of the love for the west that “asphyxiated.” There's a Bengali tradition looming that is somehow difficult for the subject of the poem to access.

And yet the book purports to be the debut collection of a young Bangladeshi poet. If so, it's pushing the envelope since in style, subject matter, language and perspective there is a lot of the contemporary U.K. in it, where Akbar arrived at age 16 and still lives. But of course traditions are not stagnant and the duality of culture in Akbar's life is hardly uncommon nowadays. Perhaps it is Bangladeshi poetry of an emerging kind.

Of himself Akbar says when in Britain he feels very Bengali but while in Bangladesh he feels like a fish out of water. As is not unusual for emigrants he fits everywhere and nowhere.

What is certain is that his poetic beginnings do belong to Bangladesh, stemming from his childhood in Dhaka. Akbar describes growing up in the 1980s as an experience with drawbacks. “There were few leisure activities,” he says, “no bowling, nothing much on TV.” The diversions largely absent, “things happened elsewhere” – his imagination took over.

The very first “poem” he recalls creating was at age seven. It was three Bangla lines: “Aasher mash / Goru khai ghash / Bhag khai hash.” “In Aasha month / Cows eat grass / Tigers eat ducks.”

During his school days, Akbar was especially popular with friends at times of special occasions. He was known for his verse-writing skills, in particular for Valentine's cards. Many a young woman was impressed by his ghost writing efforts – some married their schoolyard sweethearts only to meet the disappointment that, post-marriage, their husbands weren't writing those touching verses anymore.

“I told them to write their own,” Akbar says of those days, “but they insisted and it made me realise that this was something I could do.”

Despite following convention, studying economics and working in London's financial markets, it was clear his creativity would find its outlet. Indeed it is lack of personal satisfaction at the office that continues to lead Akbar towards literature. Initially he filled any spare hour with art exhibition, poetry reading or cinema – to engage with the arts in any way. It was the inklings of a creative rebirth that led to publishing this poetry collection and, on-the-way, his first novel.

“There comes a point when you realise,” says Akbar, “that the inner self can't cope anymore – when you start to plan, strategise and move away from the money making machine.”

I suppose it's natural that when he reached that place of courage to publish he found his voice had travelled too, to settle far from its original home. The west is evident even in his description of poetry. “Society is incredibly mechanical – convenient but robotic,” he says, “Poetry allows you to step out of that rhythm and go to that oasis that is required.” I'd hazard many a Dhakaite would hope life could be a little more robotic; and I've never heard a Bangladeshi express a desire to step out of daily life's rhythm – rather, in difficult times they step into it.

Yet according to Akbar, spending two minutes concentrating on a good poem is akin to meditation – and his poems possess something of this quality.

In the U.K., Akbar found people were more forthcoming in their opinions, less reticent about what elders might think – and it gave new clarity for free expression. It is this cold climate clarity that perhaps brings the cleanness to his work, not only in the description of emotions but also in the interesting observations of daily life, such as in the opening poem “Supermarket Oscars” which contemplates the unseen movie captured by the surveillance cameras outside a supermarket.

Another appealing aspect is the humour, especially in “A1 Elites”, a poem which depicts the least couth version of the upper class in Dhaka. Its brilliance is in the language – being at least for me the first poem encountered in that wonderful Banglish-English admixture. It starts “I hail from zamindar family / Very honourable and nicely / Trust me, my friends are also” and proceeds to list the ways in which money is made and squandered as an appeal for the reader to be impressed. “Don't be thundered to hear MiG29s, frigates / But first I must please the minister with various baits.” In this poem Akbar absolutely betrays that his is not a solely British voice.

At a personal level, as an Australian living in Bangladesh, “Tree Without Roots” fascinated – like a photographic negative of my experience – nonetheless realistic. But where the poem states that after trying “haleem, futchka, chotpoti /I saw you vomit with food poisoning” my own stomach felt at ease. More substantially, the Dhaka that “frightened” from the first day exhilarated. Perhaps because I lived in several countries – a very different experience from having lived in two, since the being torn by duality gives way to a strange conglomeration of multiplicity – I never felt without roots. Rather, I found roots everywhere. In Bangladesh they were deep, unimaginable and waiting.

The reason I mention this personal response is because I would like to see Akbar delve more deeply into his Bangladeshi heritage and its juxtaposition with a later acquired Britishness. This is an area where he could shed further light on the human condition.

Furthermore, believing in the cultural wealth of Bangladesh, I wish Akbar would take better advantage of the good fortune of having been born into the strong poetic and communicative traditions of the delta.

But on the other hand, perhaps one should not expect to find the intricacy of the renaissance in modern architecture.

What is clear is that more poetry of interest will come from Akbar. “If I don't write,” he says, “I become sad. It helps me stay sane – I write when I am desperate and the process is cathartic.”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments