BANGABANDHU AND LAPSES IN HIS SECURITY

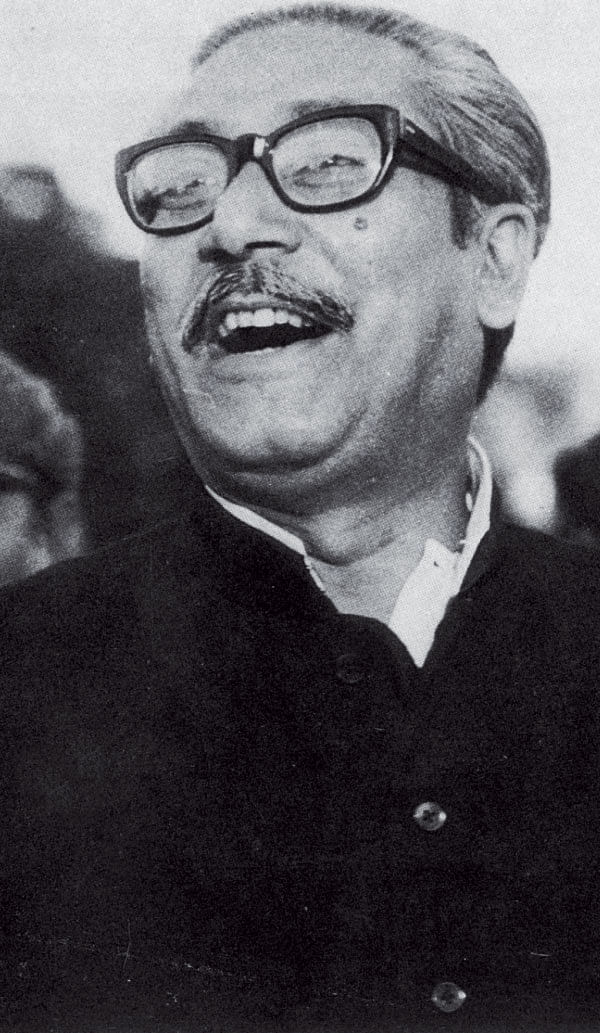

The assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family on 15 August 1975 remains testimony to the woeful absence of security around the president. All these years after the tragedy, the significant question remains: why were the intelligence agencies of the government in absolute ignorance of what was afoot? National Security Intelligence, military intelligence, the Rakkhi Bahini, the Bangladesh Rifles and the police simply did not know of the conspiracy underway to bump off the Father of the Nation. Or could it be that many of the men in these outfits knew of the approaching darkness but chose to keep quiet?

The ramifications of such a massive failure were to be far-reaching. In the immediacy of the moment, Bangabandhu was taken unawares when the soldiers, led by majors and lieutenant colonels, attacked his residence at 32 Dhanmondi in the pre-dawn hour of 15 August. The security personnel at the presidential home were easily overpowered, to a point where the killers shot down Sheikh Kamal on the ground floor of the residence and then swiftly sprinted to the first floor. Within moments, they riddled Bangabandhu with automatic arms fire. Once that was done, they went on a rampage and would not end their macabre mission until they had killed Bangabandhu's wife, three sons, two daughters-in-law, his brother and the household help. Elsewhere in the city, similar criminality was in action at the homes of Abdur Rab Serniabat, Bangabandhu's brother-in-law and member of his cabinet, and Fazlul Haq Moni, his nephew.

It is amazing that no one, especially among the army high command, had any idea of what was going on at Savar at midnight between August 14-15. Farook Rahman delivered an incendiary speech before the soldiers, making it obvious that violence would underlie their action. The argument subsequently put forward by some quarters, therefore, that the soldiers did not plan or mean to murder Bangabandhu does not hold water. The coup makers knew it would be hard to take the Father of the Nation into custody and even if they did manage to do that, they would not be able to hold him for long. Assassination, therefore, was the objective. It was achieved with precision.

Precision too was in the manner in which the tanks came out of the cantonment shortly before the carnage commenced in Dhanmondi. In the words of General KM Shafiullah, army chief of staff at the time, an officer asked him if he had any knowledge of tanks moving out of the cantonment and proceeding toward the radio station at Shahbagh and Bangabandhu's residence in Dhanmondi. Shafiullah of course had no idea of what was going on. His next move was to ask Col Shafayat Jamil, commander of 46 Brigade, if he had authorised the movement of the tanks into the city. Jamil's response was a No. It was then clear that disaster was about to happen. And it did.

Suspicion ought to have been aroused when Khondokar Moshtaq and some of his co-conspirators stayed away from Dhaka for the three days preceding the coup. With Taheruddin Thakur, ABS Safdar and Mahbub Alam Chashi, Moshtaq, then minister for commerce in Bangabandhu's government, spent the three days until 15 August at the Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) in Comilla. All four men were seen in Dhaka moments after Bangabandhu had been gunned down. It is interesting that in the final months of Bangabandhu's life, Taheruddin Thakur, minister of state for information, was a ubiquitous presence beside him. That he was in league with Moshtaq was not known.

Strangely enough, it was none other than Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi who, more than once, warned Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of the risks he was taking by neglecting the matter of his security. Unwilling to believe that any Bengali could murder him, he laughed off the Indian leader's concern despite the fact that Indian intelligence clearly had some idea of the conspiracy already underway. Additionally, it was Tajuddin Ahmad, with whom Bangabandhu had fallen out by October 1974, who rushed to the president's home not long before the tragedy to warn him of reports of a coup being planned that he had come by. Again, Bangabandhu brushed the concern aside. Tajuddin went back home in a state of distress.

General Ziaur Rahman, then deputy chief of army staff, knew of the intrigue the colonels and majors were engaged in but would have nothing to do with it. Worse was the fact that as a servant of the republic, Zia did not let General Shafiullah, the chief of staff, know what was brewing. Neither did he feel it necessary to let anyone else in the government know of the mischief that was afoot. That was when presidential security came under risk.

A major factor in the security question relating to Bangabandhu's position as Father of the Nation and as Bangladesh's President was his refusal to stay at Ganobhaban. The structure, which combined the presidential office and residence, was a good deal more secure than the Dhanmondi home where he and his family had been staying since the 1960s. One is not quite sure of the extent to which Bangabandhu's safety could have been guaranteed had he resided in the rather well-guarded Ganobhavan. It is not hard to surmise, though, that the ease with which the assassins stormed 32 Dhanmondi, scaling its low walls and running riot all over the house, would not have been possible at Ganobhavan.

In hindsight, it is now obvious that 32 Dhanmondi was always a security issue for Bangabandhu, especially after his release from the Agartala conspiracy case in February 1969. At one point following the general elections of December 1970, an intruder with a knife concealed on his person was apprehended inside the residence, which was forever occupied by crowds of Bengalis for whom entry into the residence had always been easy. On his return from incarceration in Pakistan in January 1972 and until his assassination three and a half years later, he felt little concern about his security.

People walked in and out of Bangabandhu's residence with relative ease. His security detail when he travelled along city roads was not much to write home about. The windows of his car were always open and there were times when the vehicle was seen to stop at traffic lights in the manner of ordinary citizens. He was spotted reading a newspaper as his vehicle waited for the lights to turn green.

In the darkness before dawn on 15 August 1975, the tanks rolled by Crescent Lake, unchallenged. Soon they blocked the approach to 32 Dhanmondi. A little distance away, guns were placed on top of the structure housing Kala Chand Sweets in Kalabagan, ready to fire away at 32 Dhanmondi should resistance to the coup come from within. Had presidential security been in proper order, Road 32 would be under intense security cover long before that dark morning. No tanks or any unauthorised vehicles would be able to isolate the presidential home from the rest of the country.

The bottom line: conspiracy was rich on August 15. Those responsible for Bangabandhu's security failed miserably in doing their job. They shamed the nation. They helped to push Bangladesh down the precipice.

The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments