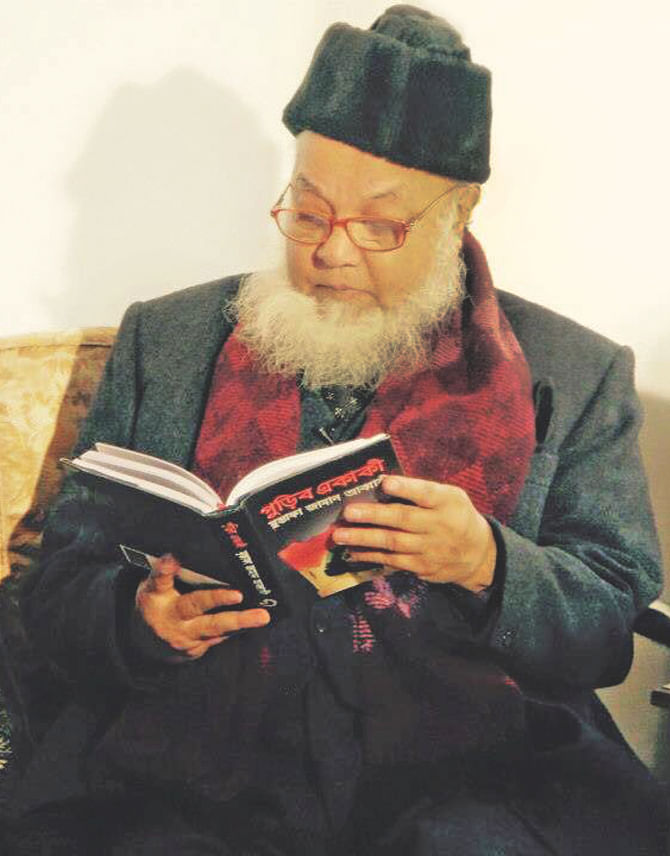

A man of judicial excellence

Eminent Supreme Court judge, former Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal is known for a jurisprudence that stood out for its emphasis on interpreting and extending the meaning of locus standi for the cause of public spirited litigation in Bangladesh, for landmark constitutional judgments, and for the family lawsuit struggles.

In the beginning of nineties, Justice M. Kamal's activism in Kudrat-E-Elahi Panir v Bangladesh (1992) 44 DLR (AD) 319 to enforce the constitutional mandate for local-level democracy is uniquely encouraging. In this seminal case, the constitutional question of non-enforceability of fundamental principles of state policy (FPSPs) was raised where he opined that Constitution being the supreme law of the land prescribes that FPSPs, which in fact embody social and economic rights, are not 'laws' themselves. To equate 'principles' with 'laws' is, he added, to go against the Constitution itself.

He was in favor of conventional notion of applying FPSPs by the State in the making of laws, or following them as the guide in interpreting Constitution and others laws, and treating them as the basis of work of State and its citizens. Though he finally held that FPSPs cannot not be judicially enforceable, to some extent his opinion signifies that non-justiciability of FPSPs does not in any way undermine the transformative character of Bangladesh Constitution and the normative abidingness of these principles other way around.

Following a long-fought jurisprudential battle and a series of initial attempts, public interest litigation in Bangladesh was formally accepted in 1996 in Dr. Mohiuddin Farooque v Bangladesh (1997) 49 DLR (AD) 1, where Justice M. Kamal held that “[W]hen a public injury or public wrong or an infraction of a fundamental rights affecting an indeterminate number of people is involved, any member of the public, being a citizen, or an indigenous association, espousing the public cause, has the right to invoke the Court's jurisdiction”.

In Hefzur Rahman v Shamsun Nahar Begum (1999) 51 DLR (AD) 172, Justice M. Kamal along with other judges of the AD overruled the HCD's ruling which was that the Muslim husband is bound to maintain his divorced wife beyond the iddat period and until she remarries. Though he wanted to avoid making a secular interpretation of Quranic verses fearing that it might lead to discrepancies and contradiction with Sharia law, subsequently he was criticised for his paternalistic outlook particularly when he viewed that it is inhumane, unjust, inequitable and unfair to impose on a husband the burden of maintaining his divorced woman.

Writing a lengthy but overall well-reasoned leading judgment in the case of Secretary, Ministry of Finance v Masdar Hossain (2000) 52 DLR (AD) 82, Justice M. Kamal began by characterising the independence of judiciary as a basic pillar of the Constitution, not to be “demolished, whittled down, curtailed or diminished in any manner” (p. 103). By employing the 'oil and water' metaphor to the distinctness of the functions performed by the civil administrative service and the constitutionally-schemed independent judicial service, the learned judge found the existing amalgamation of the 'judicial service' with the 'civil service' unconstitutional.

In this case, by invoking the principle of separation of powers, the Attorney-General argued that the Court lacked an authority to direct Parliament to enact laws or to direct the President to frame rules. Justice M. Kamal's articulate and thoughtful response was that if in any case a course of 'constitutional deviation' is found to be engineered and pursued by either Parliament or the executive, the higher judiciary can exercise its jurisdiction to bring them back to the constitutional path by giving necessary directions (p. 108).

In Constitutional Special Reference No. 1 of 1995 regarding en masse resignation of Members of Parliament (MPs), the AD was asked by the President to advise whether continuous boycotting of Parliament by opposition MPs for consecutive 90 days would render their seats vacant for being “absent” from Parliament for such a period, as constitutionally mandated in article 67(1)(b). Reported in 47 DLR (AD) 111, Justice M. Kamal intrepidly wrote that the possibility of non-acceptance of opinion by the President is not a premise with which the Court will start the exercise of an advisory rule. Rather the Court will presume that the honour due to this Court by soliciting an opinion on some questions of law will be supplemented by its acceptance and adherence. The consideration that the opinion may not be honoured has never deterred any Court from answering a Reference (p. 133).

The constitutional aptitude of Justice M. Kamal still today provokes both the academic and legal communities to undertake further inquiries and researches. Let wisdom of Justice Mustafa Kamal enlighten us forever!

The writer is LLM Student, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments